All the Pope's Men (18 page)

Read All the Pope's Men Online

Authors: Jr. John L. Allen

Functionally speaking, the level someone holds is not terribly important in terms of relations with other personnel, since employees generally do not know what number their colleagues hold. Often when two lay Vatican employees are introduced to one another, especially the Italians, this is among the first questions they ask: What’s your number? It’s considered a bit uncouth among the clerical ranks to express curiosity on the point, and usually officials have to know one another fairly well before it comes up. They know one another’s job classification—

addetto

, undersecretary, and so on—because it is published in the Vatican’s

Annuario

, its yearbook. As a rule, a priest who is a new hire for a mid-level position in a dicastery will begin at level six for a probationary period and will automatically move up to level seven within a few months. Movement up the scale depends upon time, promotion, and the goodwill of one’s superiors.

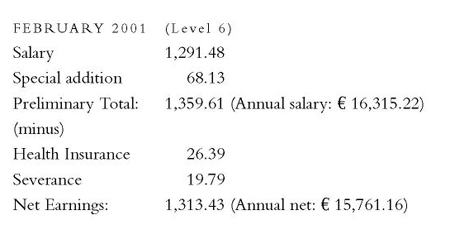

Outsiders are generally shocked at the low salaries drawn by Vatican officials, many of whom hold advanced degrees, in some cases doctorates, and who would be considered the equivalent of white-collar middle managers in any other major multinational organization. Here is a representative set of monthly pay stubs denominated in Euro from a real Vatican official, a priest who entered curial service as an

addetto di

segreteria

in February 2001:

Note: The “special addition" is an additional payment intended to offset increases in the cost of living. Twice a year a special Vatican commission meets, and, on the basis of figures generated by the Italian government regarding the rate of inflation, determines if an additional contribution to salary should be provided. The mechanism for determining the amount is complex, and the formula is based not on one’s total salary, but only a portion. Hence the addition tends to be relatively small.

Health Insurance

refers to a fund, called the Fondo Assistenza Sanitaria, which covers medical services, ambulance costs and pharmacy expenses for employees, retirees, and family members who live with or are otherwise dependent upon employees or pensioners.

Severance

refers to a payment made by the Vatican to an employee when he or she resigns, retires, is fired, or leaves at the end of a temporary contract. Generally the amount, to which both employee and employer contribute, is equivalent to one month of pay for every year of service. Someone who leaves the Vatican after twelve years will be paid a full year’s salary.

Note: The overdue category refers to a back payment owed to an employee that is now being paid. For example, if one is promoted in July but with an effective date of the preceding March 1, an overdue gross will be paid for the salary differential for those three months, along with the overdue addition to compensate for increases in the cost of living.

Note: The

bienni

is an additional monthly payment awarded after every two years of service, so someone with sixteen years in the Curia will receive a

bienni

payment that has been increased eight times. The amount is calculated on the basis of the number of years at each level of service, so if the employee was at level seven for six years, then at eight for five, then at nine for five, the

bienni

will be calculated on the basis of three different figures reflecting each of those periods of service.

After two years of service and a promotion up the pay grade, this official makes less than US $20,000 a year—an amount that most lawyers, doctors, architects, and other white-collar professionals would consider an insult as a starting salary fresh out of college. To be fair, Vatican employees receive an extra month’s pay during the second ten-day period in December of each year, which takes the place of a Christmas bonus. Still, compensation is anything but profligate. This Vatican official, by the way, travels the world representing the Holy See at international meetings, prepares speeches that are pronounced by the Pope, and is called upon to negotiate complex treaty agreements with NGOs and United Nations agencies. Yet when he travels to New York or Geneva on business, most of the time he can’t afford to go out for dinner at night unless someone else offers to pick up the tab. It goes without saying that Vatican officials are not issued company credit cards and do not have expense accounts.

A few other observations are in order. First, these earnings are untaxed. A mid-level white-collar official in the U.S. government might make $65,000 a year, but one-third is eaten up in taxes, so the official only sees $43,333 in net pay. That is, obviously, still much higher than the $18,842.72 our Vatican official nets, given Euro/U.S. dollar exchange rates as of this writing. Second, the Vatican official in question is a priest, so he does not have a family to support. By the same token, he does not have the possibility of marriage to someone bringing in a second paycheck. Whether the curial official has to pay for housing or not depends on the particular circumstances. For superiors, housing is generally provided. Cardinals are generally expected to maintain at least a minimum household staff. Lower-level officials are more on their own. American diocesan priests in curial service typically live in the Villa Stritch, a facility subsidized by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. They pay $250 a month, which includes meals. Priests of other nationalities may have to pay an amount closer to the typical costs of apartment rental in urban Rome, which can be 1,000 Euro a month. In some cases, they get lucky and find housing at a reduced cost. One Maltese official, for example, lives in an apartment owned by the English College and pays a nominal rent. Curial officials generally travel home for vacation at their own expense at least once a year, and many are required by the nature of their job to maintain a car in Rome—an expensive proposition given the demands of gas, parking, and insurance, to say nothing of routine repairs.

One big variable in how officials are able to live lies in whether or not their home diocese pays them a salary while they are in Rome. Among the Americans, some priests continue to draw full diocesan salary while working in the Vatican, which can be $25,000 or more annually. Others get a partial supplement. Still others draw nothing, which tends to be a sore point for officials in that situation. To some extent, these differences are a matter of divergent diocesan policies, but they may also sometimes come down to the personal interest a bishop takes in supporting personnel on loan to the Curia. One official in a dicastery told me that he had been working in the Vatican for two years when, on a visit to Rome, his bishop finally got around to asking him, “So, how do you get paid over here?" When he explained the salary system, the bishop immediately promised to begin sending a supplement, which has allowed this official to go back to the United States twice a year instead of once to visit his family, including his mother, who is in a nursing home.

John Paul addressed the issue of curial salaries in a November 20, 1982, letter about working in the Holy See: “Among those who collaborate with the Holy See, many are ecclesiastics, who, living a vow of celibacy, do not have within their sphere of responsibility the care of a family. Hence they merit a remuneration proportional to the duties they carry out, sufficient to assure a decorous support and to allow them to fulfill the obligations of their state in life, including those responsibilities they can have in certain cases to come to the aid of their own parents or other relatives who may depend on them. Neither should the exigencies of their particular social relations be obscured, especially the obligation to aid the needy; an obligation that, on account of their evangelical vocation, is for ecclesiastics and religious more compelling than for the laity." The Pope seemed to imply that because ecclesiastics do not have wives and children (except for clergy from one of the twenty-one Eastern Rite churches), they do not need large paychecks, though he acknowledged that in some cases family members may depend upon the official for support. The Pope also seemed to argue that the compensation of curial officials should not be so substantial that it distances or alienates them from the poor.

In the same letter, John Paul II noted that the Catholic Church has, since the birth of its modern social doctrine in the nineteenth century, supported the right of workers to organize. Yet when it comes to the Holy See, the Pope wrote that account must be taken of its “specific nature." It is not a corporate or a political reality, such as a state. The Holy See exists to perform a pastoral service to the human family, the Pope wrote, and as such calls for a special sort of collaboration on the part of those who are in its service. The implication is that a traditional union would be out of place. In fact, most priests and religious who work in the Vatican do not have any sort of collective bargaining, since the vast majority would be considered management. Lay employees do have such an association: the Associazione Dipendenti Laici Vaticani, created in 1980. It is sometimes referred to as the “Vatican union," and it is affiliated with CISL, the Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori, one of the chief Italian federations of labor unions. Yet it is not a union in the traditional sense, because it is prohibited by statute from calling a strike or from utilizing any other means of “class struggle." Its spirit is supposed to be one of cooperation. Its last major campaign came in 2000, when it pushed the Vatican to make its pension system compatible with that of the Italian government so that if employees leave Vatican service their pension is not lost.