All the King's Cooks (3 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

To control these sums efficiently the White Sticks were assisted by the cofferer, the most senior professional officer, who was the effective working head of the administration. If the Lord Great Master could be called the chairman of the board, the cofferer was the chief executive, directly responsible for obtaining the necessary funding through such bodies as the Courts of Augmentation, First Fruits and Tenths, Woods and Liveries, and also for annually submitting the book of accounts, along with the ‘book of comptrolment’, to the Exchequer, the office to which he was ultimately accountable for the administration of the household.

12

The White Sticks were also advised by three clerks of the greencloth, three clerks comptroller and four masters of the

household – two for the King’s Chamber and two for the Queen’s Side. In order to ensure that the household staff were ‘less pestered’ and to ease the problems of lodging large numbers of officers at court, only two of the masters of the household, one clerk of the kitchen and one clerk of the spicery were on duty at any one time; these worked in six-week rotating shifts, and were paid board wages for the time spent away from the court.

13

In order to provision the household, the clerk of the kitchen drew up lists of what would be required over the coming week in the kitchen offices, which included the Kitchens themselves, the Buttery, the Cellar, the Pantry, the Poultry, the Pastry and the Saucery, the Scullery and the Woodyard. Similarly the clerk of the spicery prepared lists of provisions for the Spicery, the Chandlery, the Confectionary, the Ewery, the Wafery and the Laundry once every month. These lists were submitted to the Greencloth for inspection, and then passed to the cofferer, who issued them to the ‘purveyors’, the purchasing officers of each individual office. The cofferer also provided the purveyors with an ‘imprest’, or advance of money, so that they could acquire the items specified. The provision of all the beef, mutton, veal and pork, and the fresh, sea and salt-fish which made up the bulk of the household’s diet, was the task of a separate office, the Acatery. As with other commodities, the prices to be paid were first agreed with the officers of the greencloth, usually at below market prices.

14

Bearing the King’s commission to compulsorily purchase the required supplies, the sergeant of the acatery, accompanied by a clerk comptroller, attended fairs and markets with the ready money provided by the cofferer, so as to buy his livestock at the most advantageous price. Also, they both travelled to the coast every year to arrange the purchase of all their ling (a kind of cod), ordinary cod, and other fish. Here it became more convenient and economical to enter into a contract with an individual supplier, as when Thomas Hewyt of Hythe in Kent agreed to provide the household with a whole range of fish at previously agreed prices.

15

As the various goods arrived at the palace, they would be checked for value, quality and quantity by the clerks comptroller. To ensure that they could perform this task accurately, the Black Book had given them the responsibility of checking the measures

of all the vessels used, from the hefty tuns, vats, butts, pipes, hogsheads, rundlets (casks) and barrels down to the smallest measures such as pots of wine and all sorts of other vessels such as bottles, bushels, half-bushels and pecks.

16

Similarly, all the wheat arriving at the bakehouse, the wax, the linen, the fruit and so on arriving at the spicery, the wine, beer and ale delivered to the cellars, and every other commodity too, was either accepted as satisfactory for use or rejected – in which case the purveyor would be penalised appropriately. The clerks comptroller then entered details of every incoming item in their book of records. This they would bring to the greencloth, so that the accounts could be passed for payment and the fresh deliveries compared with the ‘briefs’ which recorded the daily consumption. As a further control, each purveyor provided the clerk of his particular office with a complete list, or ‘parcel’ of the purchases he had made during the previous month, which was then passed to the clerk comptroller, via the clerk of the greencloth, for checking and entering in a book of foot of parcels. Here the word ‘foot’ referred to what was written at the foot of the accounts, the sum or total from each parcel, from which the annual expenditure was calculated. In addition, the clerk of the kitchen submitted his yearly accounts to the greencloth within two months of the year’s end, including details of outstanding creditors and any petitions for the reimbursement of any additional items of expenditure incurred during the year.

By all these means a reasonably close control of the household’s expenditure could be maintained. But this represented only one part of the Greencloth’s responsibilities. It was also in charge of the distribution and use of all provisions, which entailed keeping wastage and pilfering to a minimum – essential at a time when cooks were notorious for their prodigal personal consumption and willingness to feed their cronies at their master’s expense. According to one observer writing in 1509:

17

These fools revelling in their master’s cost

Spare no expence, not caring his damage,

But they as caitifs often thus them boast

In their gluttony, with dissolute language:

‘Be merry, companions, and lusty of courage,

We have our pleasure in dainty meat and drink,

On which things we always muse and think.’

‘Eat we and drink we therefore without all care,

With revel without measure, as long as we may.

It is a royal thing thus lustily to fare

With others meat, thus revel we alway,

Spare not the pot, another shall it pay.

When that is done, spare not for more to call.

He merely sleeps, the which shall pay for all.’

The great deceit, guile and uncleanliness

Of any scullion, or any bawdy cook,

His lord abusing for his unthriftiness.

Some for the nonce their meat lewdly dress,

Giving it a taste too sweet, too salt, or strong,

Because the servants would eat it them among …

And with what meats soever the lord shall fare,

If it be in the kitchen before it comes to the hall,

The cook and scullion must taste it first of all.

In every dish the caitifs have their hands,

Gaping as it were dogs for a bone.

When nature is content, few of them understands,

In so much that, as I trow, of them is none

That dye for age, but by gluttony each one.

The main way of preventing such abuses was to prepare detailed briefs of what had been used by the household every single day. By eight in the morning the clerk of the kitchen had to be at the greencloth with the briefs for the Kitchen, the Buttery, the Cellar, the Poultry, the Scullery and the Woodyard, the Pastry and the Saucery, and the clerk of the spicery had to be there with those of the Spicery, Chandlery, Confectionary, Ewery, Wafery and Laundry. Similarly, the acatery clerk brought in his itemised accounts for the meats and so on that had been used on the previous day. Before 9 a.m. these briefs had been inspected by the clerk of the greencloth and clerk comptroller, after which the former, in the presence of the cofferer, had to engross them – that

is, transcribe a summary of each one into a parchment main docket (the main record of the household’s daily consumption) – before dinner was served at ten.

18

Virtually all this accounting procedure took place either in the Counting House over the Back Gate, or in the offices of the comptroller, the cofferer, the clerk of the greencloth, clerk comptroller, clerk of the kitchen and clerk of the spicery, which were all arranged on the first floor of the Greencloth Yard. The security of these offices, and of their contents, was placed in the charge of the yeoman and groom of the counting house: these two would be illiterate, preferably, to ensure that they could not convey confidential information to people outside their office.

19

They had to prepare the counting house for the day’s business by eight every morning, and ensure the safekeeping of all its books and records. No officer was allowed to remove any of the accounts without the consent of at least two or three officers of the greencloth, who were then directly responsible for overseeing their prompt return. It would be a mistake, however, to believe that the officers of the greencloth were solely office-bound administrators, for their duties took them daily into the various working offices.

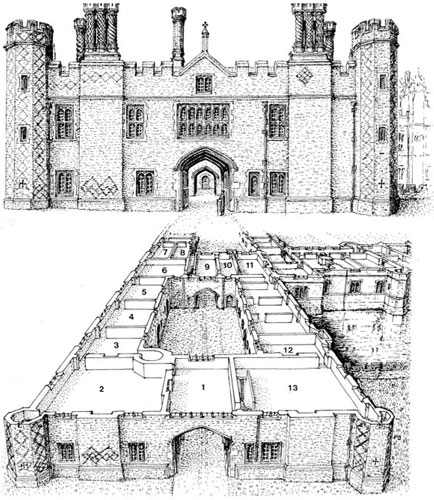

One of the most remarkable aspects of the kitchens at Hampton Court is the way they were designed to accommodate the needs of the administrators. If we assume that the various rooms identified in a survey of the lodgings of Hampton Court, taken on 4 August, 1674, had retained their original mid sixteenth century purpose – which seems reasonable in view of the conservative nature of the organisation and the lack of any substantial body of conflicting evidence – a very efficient plan soon becomes evident.

20

The placing of the offices on the first floor of the Greencloth Yard, for example, ensured that all the officers could clearly see everyone and everything entering or leaving the premises. More particularly, the clerk of the scullery and woodyard could watch the door of the coal cellar, which lay just beneath his window. And by looking westwards from their offices, both the clerk comptroller and the clerk of the kitchen could keep an eye on the doors of the fish larder, the confectionary, the pastry and the boiling house, the latter giving sole access into the main larders and kitchens.

2.

The Back Gate and the Counting House

The royal household was administered from the offices of the Counting House, which occupied the first floor above the Back Gate and around the Greencloth Yard. These rooms were occupied by:

1.

Counting House (the Greencloth)

2–5.

Comptroller’s lodgings

6.

Scullery office

7,8.

Pastry office

9.

Clerk of the kitchen’s office

10,11.

Clerks comptroller

12,13.

Cofferer

Every day the clerk of the greencloth, the clerk comptroller and the clerk of the kitchen, attended by the officers of the larder, would go into the larders, to check what remained of the previous day’s supplies and what had been recently delivered by the Acatery and the Poultry.

21

There they selected which meat and

fish were to be prepared that day and issued them to the King’s, the Queen’s and the household’s master cooks, along with instructions regarding the way they were to be dressed, so that the meat was ‘neither over much boyled or rosted’.

22

All this business had to be transacted at appropriate times so that the cooks had enough time to prepare the food for the main 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. meals.

23

For this reason, the Black Book had instructed the clerks ‘to be at couplage [cutting] of fleyshe … in the grete larder, as requiryth nightly to know the portion of beef and moton for the expences of the next day’.

24

They had also to be there well before eight every morning to check in the poultry and so forth.

Just before the meals were served, the clerk of the greencloth, the clerk comptroller and the clerk of the kitchen, probably with further clerical assistance, took up their positions in the specially designed offices next to the ‘dressers’, the serving hatches where the food was passed out from the kitchens into the hands of the waiters.

25

The dressers which served the Great Hall, where most of the household ate, were located at the southwest corner of the kitchens (no. 34). Here the dresser office, a large room heated by its own fireplace, had a broad hatch which faced across the serving area, so that the clerks, joined here by the clerk of the larder, could see that the correct quantities of the relatively basic foods that were served here were dispensed at every course.

26

At the east end of the kitchens, meanwhile, a much more sophisticated dresser office (no. 42) was recording the finer foods served for the Council Chamber and the Great Chamber (or ‘Great Watching Chamber’). From the north wall of this office, a vertical opening enabled the clerks to see across the inner side of the serving hatches, while also keeping watch on the kitchen door into the serving area and the wide service door leading towards the orchards to the north, thereby ensuring total security at the outer end of the kitchen offices. And when the hatches were opened, a further hatch in the east wall of the dresser office gave the clerks a direct view that enabled them to count all the outgoing dishes, not only from the main kitchens but also from the separate kitchen on the opposite side of the large servery area called the Great Space.

The Counting House also managed all the household’s personnel matters. The payment of wages, fees and board wages, for

example, was the respon sibility of the cofferer. To enable him to carry out this task, the clerks comptroller drew up a parchment check-roll every quarter, recording the names of every member of staff employed within the household. This was used to check everyone’s daily presence in their place of work, to confirm that those who should eat in the King’s or Queen’s chambers actually did so rather than eating privately elsewhere, and that those who had obtained leave of absence from one of the White Sticks returned to their duties by the agreed date.

27

In this way it was possible to dock the wages of all those who did not report for work. For accounting purposes, the clerks comptroller entered the payment of wages and board wages in their standing ledger, along with the purchase of provisions. They also checked whether more servants were being employed than were listed in the approved ordinances, the ‘establishment lists’, and whether any unauthorised strangers or vagabonds were being retained within the household. If such were found, the sergeant or head of the offending office was admonished and warned that if he did not immediately rectify the situation he would lose two days’ wages. For other infringements of their rules, the senior officers of the greencloth could enforce discipline, first by giving the offender a fair warning at the greencloth table; if this proved ineffective, it would be followed by the loss of a month’s wages, then imprisonment for a month; and as a last resort, exclusion from the court for ever. Also, anyone who was habitually drunk had his keys removed, and was denied access to any of the household’s provisions until he had reformed.

28