All Cry Chaos (15 page)

Authors: Leonard Rosen

"Strange but not unprecedented," said the owner of MicroScrub. "Usually, local biotech companies or the universities hire us to maintain their clean rooms. You know, for biomedical work or manufacturing computer chips. Every once in awhile we'll get a call from a civilian, so to speak."

"What did you do for Dr. Fenster?"

As the man consulted his paperwork, Poincaré checked his cell phone for text messages. Nothing from Claire or Etienne. "Standard mopping and disinfecting. At the client's request, we wiped every surface with a mild bleach solution, including books, dishes, utensils, walls, door knobs and drawer pulls."

Poincaré removed his reading glasses and looked out the hotel window, across the Charles. On a footpath, a lone runner paralleled the river. "It was the apartment's third cleaning in three days," he said, reviewing the checks once more. "Did you know this?" The owner of MicroScrub did not but added that the crew chief 's notes indicated the apartment was already clean.

Spotless

was the word in the report. "Why would someone clean an apartment that was already clean?" Poincaré asked. "You say you've done this before for individuals."

Spotless

was the word in the report. "Why would someone clean an apartment that was already clean?" Poincaré asked. "You say you've done this before for individuals."

"Medical reasons usually," the man answered. "Earlier this year we did a similar wipe-down of a house in Lexington. The owner was just coming home from one of those cancer treatments where they knock out your immune system. For the first month he had to avoid infections at all costs, so the family hired us. I'll sometimes get similar calls during allergy season—though for these people we're cleaning pollen, not germs. So we do get requests of this sort. But for the most part it's biotech and the universities."

"Did the customer explain his reasons?"

"Mr. Fenster wasn't home," said the man. "The notes show that a Mr. Silva let us into the unit and locked up behind us. The caretaker. We were paid by check in advance."

Poincaré leaned back in his chair, working through the possibilities. He had read the state police report. The investigators had full access to Fenster's medical records and certainly would have noted a health crisis. True, it had been allergy season, but a single cleaning would have managed that problem and, in any event, during the previous spring Poincaré found no similar expenses. Fenster did not hire three cleaning services to rid the apartment of ragweed.

The building was a three-storey brick box that blighted a neighborhood of century-old Victorians. Poincaré made his way down a tree-lined street along brick sidewalks that bucked and heaved. Two men stood at the entry of the apartment building, one young and slender, dressed in a suit plain enough to be a mechanic's uniform; the other, thickset with lacquered gray hair and a forest of eyebrows. From what Poincaré could see, the older man was unhappy in the extreme at being forced into polite conversation with a kindergartner who also happened to be an FBI agent. Eric Hurley was howling mad as he read, then signed, a sheet of paper. At Poincaré's approach, the veteran cop said: "I suppose you're Interpol . . . another burr in my ass. This case was closed."

Poincaré shook the detective's hand, then Agent Johnson's.

"I've heard the stories, Inspector. It's an honor. Truly."

"Well, don't start pissing yourself with excitement," said Hurley. "I'll unseal the room—" he looked at his watch—"and you'll call me when you're done and stay put until I get back. I've got things to do. And for the record, we had our best forensics teams out here after the murder. They produced IDs that confirmed all your findings in Amsterdam—so I don't mind saying that my opening this apartment so you can validate my work offends me. Just so we understand each other."

The man was perspiring and smelled of buttermilk. "I understand," said Poincaré.

"I don't care if you do or don't understand. Let me see that warrant again." When Agent Johnson produced the document, Hurley jerked open the vestibule door and climbed to the second landing, quickly for someone his size. He was just starting down the hall when he nearly knocked over a custodian who was vacuuming a carpet. In another moment, he stopped at a door where Poincaré saw adhesive labels set across the jamb at four spots, making entry impossible without breaking a seal. Hurley noted the time, initialed each label, then sliced them with a penknife. He unlocked the door and pocketed the key. "Knock yourselves out," he said. "And don't leave until I get back. Here's my number." He flipped a business card to the carpet.

Rumbling down the hall, Hurley looked like a truck driver negotiating a narrow street. The custodian pinned himself against a door to let him pass, and Agent Johnson said: "I'm betting the only two people who ever loved this guy were his mother and his football coach."

Poincaré laughed. "He's right, you know. Everything they found confirmed the forensics report in Amsterdam. As far as their end of the investigation is concerned, this case

is

closed." He had motioned to the custodian, who shut off his vacuum and approached. Poincaré explained their business.

is

closed." He had motioned to the custodian, who shut off his vacuum and approached. Poincaré explained their business.

"Finally," said the man.

"You knew Dr. Fenster?"

"Well enough."

"How well was that?" asked Poincaré.

"We'd watch the Red Sox together some nights. He'd bring pizza over to my place, maybe carry-out Chinese. I live in the basement unit, next to the heating plant."

Jorge Silva was a fragile-looking seventy-five or eighty with papery skin, sloped shoulders, and a preference for talking to the floor in the presence of strangers. He pulled at his hands to mask a tremor. "I thought the police gave up."

"We haven't," said Poincaré.

"Good. Because Jimmy Fenster deserved better. People here say

good morning

and make noises like they care. Only Jimmy cared. One time I got sick, and he came by twice a day for a week to bring soup and bread. Who else noticed? I got no family anymore. No kids to take care of me." Silva looked ready to spit. "When I think of him blown up . . ."

good morning

and make noises like they care. Only Jimmy cared. One time I got sick, and he came by twice a day for a week to bring soup and bread. Who else noticed? I got no family anymore. No kids to take care of me." Silva looked ready to spit. "When I think of him blown up . . ."

Finally

, Poincaré thought. "So you were friends?"

"Yes."

"And you'd see him how often?"

"In baseball season, at least twice a week. Otherwise, maybe once. Sometimes we'd sit outside, on the bench. Just chatting, looking at things. He liked to look at tree limbs, clouds. We'd walk down the block sometimes and get ice cream."

"What about clouds?"

Poincaré was not even sure why he asked.

"The white, puffy ones," Silva began. "He said on his very first airplane trip, to some kind of math competition, he was flying across the Midwest in summer. Just a kid at the time, maybe eight years old, and he saw the shadow of the clouds on the fields—he said they were islands and coastlines, the shadows. I said, They reminded you? And he said no, they were the same, clouds and coastlines. I don't know," said Silva. "We just enjoyed each other's company. With some people you do, with some you don't."

"Before he left for Europe," said Poincaré, "before the bombing, he hired a cleaning crew. You let them in and out. Is that right?"

"He left instructions. Three companies over three days."

"How clean does an apartment need to be, Mr. Silva?"

"It's strange. That's true."

"Did you ask?"

"No. Why should I?"

"Was Dr. Fenster sick? Did he have to keep the place that clean to avoid germs?"

"Not sick, no. He could have used twenty more pounds, but he was healthy."

"Did he have a regular cleaner?"

"No—he cleaned himself. It's a small place. You'll see."

"And the last cleaning crew," said Poincaré, his hand now on the apartment door. "Tell me about them."

Silva scratched his head. "They came with their own vacuums, detergents, dusters and a couple of machines I didn't know what. Three or four people, with gloves and paper socks over their shoes. I saw them wiping everything clean. I know somebody who does work like that down at Mass General."

"When did you see Dr. Fenster last?"

"It was a Wednesday because that night was the last game of the opening series with Tampa Bay. The Red Sox won. Jimmy stopped over with pizza. He was all packed and brought his bag with him to my place. He had just come from another trip out West, I think— gone a couple of weeks."

Poincaré knew that Fenster had spoken at conferences in Tokyo and Seattle on topics unrelated to globalization—and that he had flown into Boston for an eight-hour layover before his flight to Amsterdam. "Go on," he said.

"I think he must have come straight from the airport to have pizza with me. I'm not even sure he went back to his apartment because he told me he just came from his office and the pizza parlor, then straight here. He loved baseball. After about the fifth inning he called a cab to Logan from my place and I walked him out to the street. He said he was glad we were friends. He held up his hand and smiled."

"You shook hands."

"No." Silva raised his right hand as if he were swearing on a Bible. "He did this."

Johnson opened his forensics kit. "Mr. Silva, did the cleaners wear socks over their shoes?" He held up a blue bootie, standard issue for forensics personnel at crime scenes.

"Different color, but that's right."

"And you said they were wiping things."

"Books, glasses in the kitchen. Everything."

Poincaré pulled a photograph from his briefcase. "Do you recognize her?"

The caretaker, hands shaking, opened a hard shell case at his belt for a pair of glasses. "Sure—that's Madeleine. His fiancée. She stayed over some nights."

"And you know this because—?"

"Because no one comes or goes I don't know about." Silva shifted his weight. "I walk people's dogs, I sign for deliveries. I let workmen in, guests. I know what goes on here."

"When was it you last saw her?"

Poincaré waited for Silva to remove his glasses and snap the case shut. "Awhile ago—months, anyway. She stopped coming. And don't ask me why because I never asked."

So strong was Fenster's presence when Poincaré opened the door that Fenster himself may as well have greeted them. What Poincaré saw was more gallery than efficiency apartment. A single line of photographs, in pairs and also groupings of three or more, extended in a horizontal line at eye level across every vertical surface—windows and kitchen cabinets included. Poincaré had seen some of these, or ones very like them, in Amsterdam: photos of trees in full leaf and in winter, lightning strikes, mountain ranges. Each image was trimmed to an identical dimension and was set in an identical black frame with cream matting against stark white walls. Fenster had moved what few pieces of furniture he owned toward the center of the room to create a perimeter space for his gallery, a layout that forced the observer to regard images in their groupings and from a set distance. Nothing had prepared Poincaré for the beauty and strangeness of this display.

"Not your average genius," remarked Johnson.

Poincaré scanned the room.

"With the place wiped down by three different crews, Inspector, I'm wondering how the state police found

any

prints or DNA, let alone samples that corroborated your results in Amsterdam. Back in Virginia we'd call that a puzzle."

any

prints or DNA, let alone samples that corroborated your results in Amsterdam. Back in Virginia we'd call that a puzzle."

Poincaré took a quick inventory: wooden table, boney chair, thin mattress on an iron spring frame, single bookcase, galley kitchen with a frying pan, pot, and tea kettle. No radio, no television. No phone. No crosses on the walls or Buddhas on altars. Only Fenster's monkish belongings in a room that, photos aside, was as spare as a prison cell. A large box held dozens of additional photos, which Fenster must have rotated through the gallery.

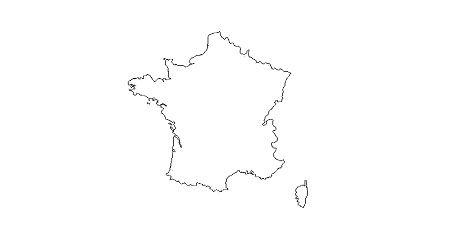

Johnson approached a grouping of six images that had rattled Poincaré the moment he entered the room. When the agent reached for the first in the series, Poincaré said: "Vive la France. It's the national boundary."

"The next image shows the borders of my country's twenty-two regions. Next, the one hundred departments. Then the three-hundred forty-two arrondissements."

Other books

House of Secrets by Columbus, Chris, Vizzini, Ned

Entangled Interaction by Cheyenne Meadows

Virginia Woolf by Ruth Gruber

Twenty Palaces by Harry Connolly

It Should Be a Crime by Carsen Taite

The Marathon Conspiracy by Gary Corby

The Regency Detective by David Lassman

All Other Nights by Dara Horn

Hasta luego, y gracias por el pescado by Douglas Adams

Random Acts Of Crazy by Kent, Julia