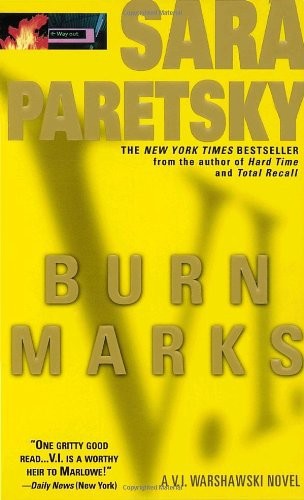

Burn Marks

Authors: Sara Paretsky

Burn Marks

V.I. Warshawski – Book 6

By Sara Paretsky

1

Wake-up Call

My mother and I were trapped in her bedroom, the tiny upstairs room of our old house on Houston. Down below the dogs barked and snapped as they hunted us. Gabriella had fled the fascists of her native Italy but they tracked her all the way to South Chicago. The dog’s barking grew to an ear-splitting roar, drowning my mother’s screams.

I sat up. It was three in the morning and someone was leaning on the doorbell. I was sweaty and trembling from the dream’s insistent realism.

The urgent ringing recalled all the times in my childhood the phone or doorbell had roused my father to some police emergency. My mother and I would wait up for his return. She refused to admit her fear, although it stared at me through her fierce dark eyes, but would make sweet children’s coffee for me in the kitchen—a tablespoon of coffee mixed with milk and chocolate—and tell me wild Italian folktales that made my heart race.

I pulled on a sweatshirt and shorts and fumbled with the locks to my door. The ringing echoed through the stairwell behind me as I stumbled down the three flights to the front entryway.

My aunt Elena stood on the other side of the glass door, her finger pressed determinedly to the bell. A faded quilt made an ungainly cloak around her shoulders. She had propped a vinyl duffel bag against the wall; a violet nightgown trailed from its top. I don’t believe in prescience or ESP, but I couldn’t help feeling that my dream—a familiar childhood nightmare—had been caused by some murky vibrations emanating from Elena to my bedroom.

My father’s younger sister, Elena had always been the family Problem. “She drinks a little, you know,” my grandmother Warshawski would tell people in a worried whisper after Elena had passed out at Thanksgiving dinner. More than once an embarrassed patrolman roused my dad at two in the morning to tell him Elena had been busted for soliciting on Clark Street. On those nights there were no fairy tales in the kitchen. My mother would send me to my own bed with a tiny shake of the head, saying, “It’s her nature, cara, we mustn’t judge her.”

When my grandmother died seven years ago, my father’s surviving brother, Peter, gave his share of the Norwood Park bungalow to Elena on condition that she never ask him for anything else. She blithely signed the papers, but lost the bungalow four years later—without talking to me or Peter she had put it up as collateral in a wild development venture. When the fly-by-night company evaporated, she was the only partner the courts could find—they confiscated the house and sold it to meet the limited partnership’s bills.

Three thousand remained after paying the debts. With that and her social security, Elena had been living in an SRO at Cermak and Indiana, playing a little twenty-one and still turning the occasional trick on the day the pension checks arrived. Despite years of drinking that had carved narrow furrows in her chin and forehead, she had remarkably good legs.

She caught sight of me through the glass and took her finger from the bell. When I opened the door she put her arms around me and gave me an enthusiastic kiss.

“Victoria, sweetie, you look terrific!”

The sour yeasty smell of stale beer poured over me. “Elena—what the hell are you doing here?”

The generous mouth pouted. “Baby, I need a place to stay. I’m desperate. The cops were going to take me to a shelter but of course I remembered you and they brought me here instead. A very nice young man with an absolutely gorgeous smile. I told him all about your daddy but he was just a boy, of course he’d never met him.”

I ground my teeth together. “What happened to your hotel? They kick you out for screwing the old-age pensioners?”

“Vicki, baby—Victoria,” she amended hastily. “Don’t talk dirty—it doesn’t sound right coming from a sweet girl like you.”

“Elena, cut the crap.” As she started a second reproach I corrected myself hastily. “I mean stop talking nonsense and tell me why you’re out on the streets at three in the morning.”

She pouted some more. “I’m trying to tell you, baby, but you keep interrupting. There was a fire. Our lovely little home was burned to the ground. Burned to an absolute crisp.”

Tears welled in her faded blue eyes and coursed through deep furrows to her neck. “I hadn’t gone to sleep yet and I just had time to stuff my thing into a suitcase and get down the fire escape. Some people couldn’t even do that much. Poor Marty Holman had to leave his false teeth behind,” The tears stopped as abruptly as they began, to be replaced by a high-pitched giggle. “You should have seen him, Vicki, my God, you should have seen what the old geezer looked like with his cheeks all sunk in and his eyes popping out and him shouting in this mumbly kind of way, ‘My teeth, I’ve lost my teeth.’”

“It must have been hilarious,” I said dryly. “You cannot live with me, Elena. It would drive me to homicide within forty-eight hours. Maybe less.”

Her lower lip started to tremble again and she said in a terrible parody of baby talk, “Don’t be mean to me, Vicki, don’t be mean to poor old Elena, who got burned out of her house in the middle of the nights. You’re my own goddamn flesh and blood, my favorite brother’s little girl. You can’t toss poor old Elena out on the street like some worn-out mattress.”

A door slammed sharply behind us. The banker who had just moved into the first-floor-north apartment erupted into the stairwell, his hands on his hips, his jaw sticking out pugnaciously. He was wearing navy-striped cotton pajamas; despite the bleary sleep in his face, his hair was perfectly combed.

“What the hell is going on out here? You may not have to work for a living—God knows what you do all day long up there—but I do. If you have to conduct your business in the middle of the night, show some consideration for your neighbors and don’t do it out in the hall. If you don’t shut up and get the hell out of here, I’m calling the cops.”

I stared at him coldly. “I run a crack house upstairs. This is my supplier. You could be arrested for complicity if you’re found hanging around out here when the police arrive.”

Elena giggled, but said, “Don’t be rude to him, Victoria— you never know when you may want a boy with fabulous eyes like that to do something for you.” She added to the banker, “Don’t worry, sweetie, I’m just coming in. We’ll let you get your beauty sleep.”

Behind the closed door to one-south a dog began to bark. I ground my teeth some more and hustled Elena inside, snatching her duffel bag from her when she began wobbling under its weight.

The banker watched us through narrowed eyes. When Elena lurched against him he made a face of pure horror and retreated hastily to his apartment, fumbling with the lock. I tried moving Elena upstairs, but she wanted to stop and talk about the banker, demanding to know why I hadn’t asked him to carry her bag.

“It would have been a perfect way for you two to get acquainted, make things up a little.”

I was close to screaming with frustration when the door to one-south opened. Mr. Contreras came out, a staggering sight in a crimson dressing gown. The golden retriever I share with him straining against her collar, but when she saw me her low-throated growls changed to whimpers of excitement.

“Oh, it’s you, doll,” the old man said with relief. “The princess here woke me up and then I heard all the noise and thought, Oh my God, the worst is happening, someone’s breaking in in the middle of the night. You oughta be more considerate, doll—it’s hard for people who have to work to get up in the middle of the night like this.”

“Yes, it is,” I agreed brightly. “And contrary to public opinion, I am one of those working people. And believe me, I had no more desire to get out of bed at three A.M. than you did.”

Elena put on her warmest smile and stuck out her hand to Mr. Contreras like Princess Diana greeting a soldier. “Elena Warshawski,” she said. “Charmed to meet you. This little girl is my niece, and she’s the prettiest, sweetest niece anybody could hope for.”

Mr. Contreras shook her hand, blinking at her like an owl with a flashlight in its face. “Pleased to meet you,” he said automatically if unenthusiastically. “Look, doll, you oughta get this lady—your aunt, you say?—you oughta get her up to bed. She ain’t doing too great.”

The sour yeast smell had swept over him too. “Yep, that’s just what I’ll do. Come on, Elena, Let’s get upstairs. Beddy-bye time.”

Mr. Contreras headed back to his apartment. The dog was annoyed—if we were all having a party she wanted to join in.

“That wasn’t very polite of him,” Elena sniffed as Mr. Contreras’s door closed behind us. “Didn’t even tell me his own name when I went out of my way to introduce myself.”

She grumbled all the way up the stairs. I didn’t say anything, just kept a hand in the small of her back to propel her in the right direction, urging her on when she tried to stop for a breather at the second-floor landing.

Back in my apartment she wanted to ooh and aah over all my possessions. I ignored her and moved the coffee table so I could pull the bed out of the couch. I made it up and showed her where the bathroom was.

“Now listen, Elena. You are not staying here more that one night. Don’t even think I’m going to waffle on this because I won’t.”

“Sure, baby, sure. What happened to your ma’s piano? You sell it or something to buy this sweet little grand?”

“No,” I said shortly. My mother’s piano had been destroyed in the fire that gutted my own apartment three years earlier. “And don’t think you can make me forget what I’m saying by raving over the piano. I’m going back to bed. You can sleep or not as you please, but in the morning you’re going someplace else.”

“Oh, don’t look so ugly, Vicki. Victoria, I mean. It’ll ruin your complexion if you frown like that. And where else am I supposed to turn in the middle of the night if not to my own flesh and blood?”

“Knock it off,” I said wearily. “I’m too tired for it.”

I shut the hall door without saying good night. I didn’t bother to warn her not to rummage around for my liquor—if she wanted it badly enough, she’d find it, then apologize to me a hundred times the next day for breaking her promise not to drink it.

I lay in bed unable to sleep, feeling the pressure of Elena’s presence from the next room. I could hear her scrabbling around for a while, then the hum of the TV turned conscientiously to low volume. I cursed my uncle Peter for moving to Kansas City and wished I’d had the foresight to hightail it to Quebec or Seattle or some other place equally remote from Chicago, Around five, as the birds began their predawn twittering, I finally dropped into an uneasy sleep.

2

The Lower Depths

The doorbell jerked me awake again at eight. I pulled my sweatshirt and shorts back on and stumbled into the living room. Nobody answered my query through the intercom. When I looked out the living-room window at the street, I could see the banker heading toward Diversey, his shoulders bobbing smugly. I flicked my thumb at his back.

Elena had slept through the episode, including my loud calls through the intercom. For a moment I felt possessed by the banker’s angry impulse—I wanted to wake her and make her as uncomfortable as I was.

I stared down at her in disgust. She was lying on her back, mouth open, ragged snores jerking out as she inhaled, puffy short breaths as she exhaled. Her face was flushed. The broken veins on her nose stood out clearly. In the morning light I could see that the violet nightgown was long overdue for the laundry. The sight was appalling. But it was also unbearably pathetic. No one should be exposed to an outsider’s view while she’s sleeping, let alone someone as vulnerable as my aunt.

With a shudder I moved hastily to the back of the apartment. Unfortunately her pathos couldn’t quell my anger at having her with me. Thanks to her, my head felt as though someone had dumped a load of gravel in it. Even worse, I was making a presentation to a potential client tomorrow. I wanted to finish my charts and get them turned into transparencies. Instead, it looked as though I’d be spending the day hunting for housing. Depending on how long that took, I could end up paying as much as quadruple overtime for the transparencies.

I sat on the dining-room floor and did some breathing exercises, trying to ease my knotted stomach. Finally I managed to relax enough to do my prerun stretches.

Not wanting to see Elena’s flushed face again, I went down the back way, picking up Peppy outside Mr. Contreras’s kitchen door. The old man stuck his head out and called to me as I closed the gate; I pretended not to hear him. I wasn’t able to be similarly deaf when I got back—he was waiting for me, sitting on the back stairs with the Sun-Times, checking out his day’s picks for Hawthorne. I tried leaving the dog and escaping up the stairs but he grabbed my hand.

“Hang on a second there, cookie. Who was that lady you was letting in last night?” Mr. Contreras is a retired machinist, a widower with a married daughter whom he doesn’t particularly like. During the three years we’ve been living in the same building he’s attached himself to my life like an adoptive uncle—or maybe a barnacle.

I jerked my hand free. “My aunt. My father’s younger sister. She has a penchant for old men with good retirement benefits, so make sure you have all your clothes on if she stops by to chat this afternoon.”

That kind of comment always makes him huffy. I’m sure he heard—and said—plenty worse on the floor in his machinist days—but he can’t take even oblique references to sex from me. He turns red and gets as close to being angry as someone with his relentlessly cheerful disposition can manage.

“There’s no need to talk dirty to me,” he snapped. “I’m just concerned. And I gotta say, cookie, you shouldn’t let people come see you at all hours like that. Least, if you do, you shouldn’t keep them down in the hall talking loud enough to wake every soul in the building.”

I felt like wrenching one of the loose slats from the stairwell railing and beating him with it. “I didn’t invite her,” I shrieked. “I didn’t know she was coming. I didn’t want her here. I didn’t want to wake up at three in the morning.”

“There’s no need to shout,” he said severely. “And even if you wasn’t expecting her, you could’a gone up to your apartment to talk.”

I opened and shut my mouth several times but couldn’t construct a coherent response. Anyway, I’d kept Elena in the hall in hopes she’d feel hurt enough to just pick up the duffel bag and go. But even as I’d done it I’d known in my heart of hearts that I couldn’t turn her away at that hour. So the old man was right. Agreeing with him didn’t make me any happier.

“Okay, okay,” I snapped. “It won’t happen again. Now get off my back—I’ve got a lot to do today.” I stomped up the stairs to my kitchen.

Muted snores still seeped through the closed door from the living room. I made a pot of coffee and took a cup into the bathroom with me while I showered. Bent on leaving the apartment as fast as possible, I pulled on jeans and a white shirt and stopped in the kitchen to scratch together a breakfast.

Elena was sitting at the breakfast table. She’d put a soiled quilted dressing gown over the violet nightie. Her hands shook slightly; she used both of them to lift a cup of coffee to her mouth.

She produced an eager smile. “Wonderful coffee you make, baby. Just as good as your ma’s.”

“Thank you, Elena.” I opened the refrigerator door and took stock of the meager contents. “I’m sorry I can’t stay to chat, but I want to try to find you someplace to sleep tonight.”

“Aw, Vicki—Victoria, I mean. Don’t rush around like that. It ain’t good for the heart. Let me stay here, just for a few days, anyway. Get over the shock of living through that inferno last night. I promise I won’t bother you any. And I could get the place cleaned up a little while you’re at work.”

I shook my head implacably. “No way, Elena. I will not have you living here. Not one night longer.”

Her face puckered. “Why do you hate me, baby? I’m your own daddy’s sister. Family has to stick by family.”

“I don’t hate you. I don’t want to live with anyone, but you and I lead especially incompatible lives. You know as well as I that Tony would say the same if he were still around.”

There’d been a painful episode when Elena announced her independence from my grandmother and moved into her own apartment. Finding solitude not to her liking, she’d shown up at our house in South Chicago one weekend. She’d stayed three days. It wasn’t my fierce mother who’d asked her to leave—Gabriella’s love of the underdog somehow could encompass even Elena. But my easygoing father came home from the graveyard shift on Monday to find Elena passed out at the kitchen table. He put her into a detox unit at County and refused to talk to her for six months after she got out.

Elena apparently also remembered this episode. The pouty puckering disappeared from her face. She looked stricken, and somehow more real.

I squeezed her shoulder gently and offered to make her some eggs. She shook her head without speaking, watching me silently while I spread anchovy paste on toast. I ate it quickly and left before pity could overcome my judgment.

It was well past nine now. The morning rush was ending and I had an easy run across Belmont to the expressway. When I neared the Loop, though, the traffic congealed as we moved through a construction maze. The four miles on the Ryan between the Eisenhower and Thirty-first, supposedly the busiest eight lanes of traffic anywhere in the known universe, had finally crumbled under the stress of the semi’s. The southbound lanes were closed while the feds performed reconstructive surgery.

My little Cavalier bounced between a couple of sixty-tonners as the slow lines of traffic snaked around the construction barricades. To my right the surface of the old roadbed had been completely removed; lattices of the reinforcing bars were exposed. They looked like tightly packed nests of vipers—here and there a rusty head stood up prepared to strike.

The turnoff to Lake Shore Drive had been so cleverly disguised that I was parallel with the barrel blocking one of the exit lanes before I realized it. With my sixty-ton pal close on my tail, I couldn’t stand on the brakes and swerve around the barrel. I gnashed my teeth and rode down to Thirty-fifth, then took side streets up to Cermak.

Elena’s SRO had stood a few doors north of the intersection with Indiana. A niggling doubt I’d had in her story vanished when I pulled up across the street from it. The Indiana Arms Hotel—transients welcome, rates by the day or by the month—had joined the other derelicts on the street in retirement. I parked and went over to look at the skeleton.

When I walked around to the north side of the building, I discovered a man in a sport jacket and hard hat poking around in the rubble. Every now and then he’d pick up some piece of debris with a pair of tongs and stick it into a plastic bag. He’d mark the bag and mutter into a pocket Dictaphone before continuing his exploration. He spotted me when he turned east to poke through a promising tell. He finished picking up an object and marking its container before coming over to me.

“You lose something here?” His tone was pleasant but his brown eyes were wary.

“Just sleep. Someone I know lived here until last night—she showed up at my place early this morning.”

He pursed his lips, weighing my story. “In that case, what are you doing here now?”

I hunched a shoulder. “I guess I wanted to see it for myself. See if the place was really gone before I put all my energy into finding her a new home. Come to that, what are you doing here? A suspicious person might think you were making off with valuables.”

He laughed and some of the wariness left his face. “They’d be right—in a way I am.”

“Are you with the fire department?”

He shook his head. “Insurance company.”

“Was it arson?” I’d been so bogged down in the sludge of family relations, I hadn’t even wondered how the fire started.

His caution returned. “I’m just collecting things. The lab will give me a diagnosis.”

I smiled. “You’re right to be careful—you don’t know who might come around in the aftermath of a blaze like this. My name’s V. I. Warshawski. I’m a private investigator when I’m not looking for emergency housing. And I do projects for Ajax Insurance from time to time.” I pulled a card from my bag and handed it to him.

He wiped a sooty hand on a Kleenex and shook mine. “Robin Bessinger. I’m with Ajax’s arson and fraud division. I’m surprised I haven’t heard your name.”

It didn’t surprise me. Ajax employed sixty thousand people around the world—no one could possibly keep track of all of them. I explained that my work for them had been in claims or reinsurance and gave him a few names he’d be likely to recognize. He thawed further and confided that the signs of arson were quite clear.

“I’d show you the places where they poured accelerant but I don’t want you in the building if you don’t have a hard hat. Chunks of plaster keep falling down.”

I showed suitable regret at being denied this treat. “The owner buy a lot of extra insurance lately?”

He shook his head. “I don’t know—I haven’t seen the policies. They just asked me to get on over before the vandals took too much of the evidence. I hope your friend got all her stuff out—not too much survived this blast.”

I’d forgotten to ask Elena if anyone had been badly hurt. Robin told me the police Violent Crimes Unit would have joined the Bomb and Arson Squad in force if anyone bad died.

“You wouldn’t have been allowed to park without showing good reason for being near the premises—it’s a fact of life that torchers like to come back to see if the job got done right. No one was killed, but a good half dozen were ferried to Michael Reese with burns and respiratory problems. Torchers usually like to make sure a building can be cleared—they know an investigation into an old dump like this won’t get too much attention if there aren’t any murder charges to excite the cops.” He looked at his wrist. “I’d like to get back to work. Hope your friend finds a new place okay.”

I agreed fervently and went off to start my hunt with an easy optimism bred of ignorance. I began at the Emergency Housing Bureau on south Michigan where I joined a long line. There were woman and children of all ages, old men muttering to themselves, rolling their eyes wildly, women anxiously clutching suitcases or small appliances— a seemingly endless sea of people left on the streets from some crisis or other yesterday.

The high counters and bare walls made us feel as though we were suppliants at the gates of a Soviet labor camp. There weren’t any chairs; I took a number and leaned against the wall to wait my turn.

Next to me a very pregnant woman of about twenty holding a large infant was struggling with a toddler. I offered to hold the baby or amuse the two-year-old.

“It’s all right,” she said in a soft slow voice. “Todd just be tired after staying up all night. We couldn’t get into the shelter ′cause the one they sent us to don’t allow babies. I couldn’t get me no bus fare to come back here and get them to find us a different place.”

“So what did you do?” I didn’t know which was more horrible—her plight or the resigned gentle way she talked about it.

“Oh, we found us a park bench up at Edgewater by the shelter. The baby sleep but Todd just couldn’t get comfortable.”

“Don’t you have any friends or relatives to help you out? What about the baby’s father?”

“Oh, he be trying to find us a place,” she said listlessly. “But he can’t get no job. And my mother, we used to stay with her, but she had to go into the hospital, now it look like she going to be sick a long time and she can’t keep up on her rent.”

I looked around the room. Dozens of people were waiting ahead of me. Most of them had my neighbor’s dragged-out look, bodies stooped over from too much shame. Those who didn’t were pugnacious, waiting to take on a system they couldn’t possibly beat. Elena’s needs—my needs—could certainly take a far backseat to their demands for emergency shelter. Before I took off I asked if Todd and she would like some breakfast—I was going over to the Burger King to get something.

“They don’t let you eat in here, but Todd could maybe go with you and get something.”

Todd showed a great disinclination to be separated from his mother, even to get some food. Finally I left him whimpering at her side, went to the Burger King, got a dozen breakfast buns with eggs and wrapped the lot in a plastic bag to conceal the fact that it was food. I handed it to the woman and left as fast as I could. My skin was still trembling.