Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 20 (22 page)

Read Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 20 Online

Authors: A Double Life (v1.1)

“I

do not forget him;” and the hand that wore the ring closed with an ominous

gesture, which I well understood. “Monsieur merely claims his own, and the

other, being a man of sense and honor, w ill doubtless witipdraw at once; and

though ‘desolated,’ as the French say, will soon console himself with a new’

inamorata.

If he is so unw ise as to oppose Monsieur, w ho by the by is a dead shot, there

is but one wav in which both can receive satisfaction."

A

significant emphasis on the last word pointed his meaning, and the smile that

accompanied it almost goaded me to draw the sword I wore, and offer him that

satisfaction on the spot. I felt the color rise to my forehead, and dared not

look up, but leaning on the back of Clotilde’s chair, I bent as.

if

to speak to her.

“Bear

it a little longer for my sake, Paul,” she murmured, with a look of love and

despair, that

wrung my heart. Here some one spoke of a long

rehearsal in the morning, and the lateness of the hour.

“A

farewell toast before we part,” said Keen. “Come, Lamar, give us a sentiment,

after that whisper you ought to be inspired.”

“I

am. Let me give you —

The

love of liberty and the

liberty of love.”

“Good!

That would suit the hero and heroine of

St. John’s

story, for Monsieur wished much for his

liberty, and, no doubt, Madame will for her love,” said Denon, while the

glasses were filled.

Then

the toast was drunk with much merriment and the party broke up. While detained

by one of the strangers, I saw

St. John

approach Clotilde, who stood alone by the

window, and speak rapidly for several minutes. She listened with half-averted

head, answered briefly, and w rapping the mantilla closely about her, swept

away from him with her haughtiest mien. He watched for a moment, then followed,

and before I could reach her, offered his arm to lead her to the carriage. She

seemed about to refuse it, but something in the expression of his face

restrained her; and accepting it, they w

ent

down

together. The hall and little ante-room w ere dimly lighted, but as I slowly

followed, I saw her snatch her hand away, w hen she thought they were alone;

saw him draw her to him with an embrace as fond as it was irresistible; and

turning her indignant face to his, kiss it ardently, as he said in a tone, both

tender and imperious —

“Good

night, my darling. I give you one more day, and then I claim you.”

“Never!”

she answered, almost fiercely, as he released her. And w ishing me pleasant

dreams, as he passed, went out into the night, gaily humming the burden of a song

Clotilde had often sung to me.

The

moment we were in the carriage all her self-control deserted her, and a tempest

of despairing grief came over her. Lor a time, both w'ords and caresses were

unavailing, and I let her w eep herself calm before I asked the hard question —

“Is

all this true, Clotilde?”

“Yes,

Paul, all true, except that he said nothing of the neglect, the cruelty, the

insult that I bore before he left me. I was so young, so lonely, I was glad to

be loved and cared for, and I believed that lie would never change. I cannot

tell you all I suffered, but I rejoiced when I thought death had freed me; I

would keep nothing that reminded me of the bitter past, and went away to begin

again, as if it had never been.”

“Why

delay telling me this? Why let me learn it in such a strange and sudden way?”

“Ah,

forgive me!

1

am

so proud I could not bear to tell vou that

any man had wearied of me and deserted me. I meant to tell vou before our

marriage, but the fear that

St. John

was alive haunted me, and till it was set at rest I would not speak.

To-night there was no time, and I w as forced to leave all to chance. He found

pleasure in tormenting me through you, but would not speak out, because he is

as proud as I, and does not wish to hear our storv bandied from tongue to

tongue.”

“What

did he say to you, Clotilde?”

“He

begged me to submit and return to him, in spite of all that has passed; he w

arned me that if we attempted to escape it would be at the peril of your life,

for he would most assuredlv follow’ and find us, to whatever corner of the

earth we might fly; and he will, for he is as relentless as death.”

“What

did he mean bv giving vou one day more?” I asked, grinding my teeth with

impatient rage as I listened.

“He

gave me one day to recover from mv surprise, to prepare tor my departure w ith

him, and to bid you farewell.”

“And

will you, Clotilde?”

“No!”

she replied, clenching her hands with a gesture

ot

dogged resolution, while her eves glittered in the darkness. “I never will submit;

there must be some way of escape; I shall find it, and it I do not — I can

die.”

“Not

vet, dearest; we will appeal to the law first; I have a friend w hom I will

consult to-morrow’, and he may help us.”

“I

have no faith in law,” she said, despairingly, “money and

influence

so often outweigh

justice and mercy. I have no witnesses, no friends, no

wealth to help me; he has all, and we shall only be defeated. I must devise

some surer way. Let me think a little; a womans wit is quick when her heart

prompts it."

I

let the poor soul flatter herself with vague hopes; but 1 saw' no help for us

except in flight, and that she would not consent to, lest it should endanger

me.

More than once I said savagely within myself, “I will

kill him,” and then shuddered at the counsels of the devil, so suddenly roused

in my own breast.

As if she divined my thought by instinct, Clotilde

broke the heavy silence that followed her last words, by clinging to me with

the imploring cry,

“Oh,

Paul, shun him, else your fiery spirit will destroy you. He promised me he

would not harm you unless we drove him to it. Be careful, for my sake, and if

any one must suffer let it be miserable me.”

I

soothed her as I best could, and when our long, sad drive ended, bade her rest

while I worked, for she would need all her strength on the morrow. Then I left

her, to haunt the street all night long, guarding her door, and while I paced

to and fro without, I watched her shadow come and go before the lighted window

as she paced within, each racking our brains for some means of help till day

broke.

CHAPTER III

Early

on the following morning I consulted my friend, but when I laid the case before

him he gave me little hope of a happy issue should the attempt be made. A

divorce was hardly possible, when an unscrupulous man like

St. John

was bent on opposing it; and though no

decision could force her to remain with him, we should not be safe from his

vengeance, even if we chose to dare everything and fly together. Long and

earnestly we talked, but to little purpose, and I went to rehearsal with a

heavy heart.

Clotilde

was to have a benefit that night, and what a happy day I had fancied this would

be; how carefully I had prepared for it; what delight I had anticipated in

playing Romeo to her Juliet; and how eagerly I had longed for the time which

now seemed to approach with such terrible rapidity, for each hour brought our

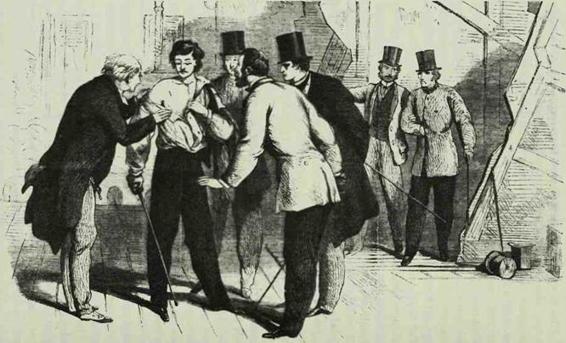

parting nearer! On the stage I found Keen and his new friend amusing

themselves

with fencing, while waiting the arrival of some

of the company. I was too miserable to be dangerous just then, and when

St. John

bowed to me with his most courteous air, I

returned the greeting, though I could not speak to him. I think he saw mv

suffering, and enjoyed it with the satisfaction of a cruel nature, but he

treated me with the courtesy of an equal, which new demonstration surprised me,

till, through Denon, I discovered that having inquired much about me he had

learned that I was a gentleman by birth and education, which fact accounted for

the change in his demeanor. I roamed restlessly about the gloomy green room and

stage, till Keen, dropping his foil, confessed himself outfenced and called to

me.

“Come

here, Lamar, and try a bout with

St. John

. You are the best fencer among us, so, for

the honor of the companv, come and do your best instead of playing Romeo before

the time.”

A

sudden impulse prompted me to comply, and a few passes proved that I was the

better swordsman of the two. This annoved

St. John

, and though he complimented me with the

rest, he would not own himself outdone, and we kept it up till both grew w arm

and excited. In the midst of an animated match between us, I observed that the

button was off his foil, and a glance at his face assured me that he was aware

of it, and almost at the instant he made a skilful thrust, and the point

pierced my flesh. As I caught the foil from his hand and drew it out with an

exclamation of pain, I saw a gleam of exultation pass across his face, and knew

that his promise to Clotilde was but idle breath. My comrades surrounded me

with anxious inquiries, and no one was more surprised and solicitous than

St. John

. The wound was trifling, for a picture of

Clotilde had turned the thrust aside, else the force with which it was given

might have rendered it fatal. I made light of it, but hated him with a

redoubled hatred for the cold-blooded treachery that would have given to

revenge the screen of accident.

The

appearance of the ladies caused us to immediately ignore the mishap, and

address ourselves to business. Clotilde came last, looking so pale it was not

necessary for her to plead illness; but she went through her part with her

usual fidelity, while her husband watched her with the masterful expression

that nearly drove me wild. He haunted her like a shadow, and she listened to

him with the desperate look of a hunted creature driven to bay. I

Ie

might have softened her just resentment by a touch of

generosity or compassion, and won a little gratitude, even though love was

impossible; but he was blind, relentless, and goaded her beyond endurance,

rousing in her fiery Spanish heart a dangerous spirit he could not control. The

rehearsal was over at last, and l approached (do- tilde with a look that mutely

asked if I should leave her.

St. John

said something in a low voice, but she

answered sternly, as she took my arm with a decided gesture.

“My comrades surrounded me with anxious

inquiries

“This

day is mine; I will not be defrauded of an hour,” and we went away together for

our accustomed stroll in the sunny park.

A

sad and memorable walk was that, for neither had any hope with which to cheer

the other, and Clotilde grew gloomier as we talked. I told her of mv fruitless

consultation, also of the fencing match; at that her face darkened, and she

said, below her breath, “I shall remember that.”

We

walked long together, and I proposed plan after plan, all either unsafe or

impracticable. She seemed to listen, but when

I

paused she answered with averted eyes —

“Leave

it to me; I have a project; let me perfect it before I tell you. Now I must go

and rest, for I have had no sleep, and I shall need all mv strength for the

tragedy to-night.”

All

that afternoon I roamed about the city, too restless for anything but constant

motion, and evening found me ill prepared tor my now doubly arduous duties. It

was late when I reached the theatre, and I dressed hastily. My costume was new

for the occasion, and not till it w as on did I remember that I had neglected

to try it since the finishing touches were given. A stitch or two would remedy

the defects, and, hurrying up to the wardrobe room, a skilful pair of hands

soon set me right. As I came down the winding- stairs that led from the lofty

chamber to a dimly-lighted gallery below, St. John’s voice arrested me, and

pausing I saw that keen w as doing the honors of the theatre in defiance of all

rules. Just as they reached the stair-foot some one called to them, and

throwing open a narrow door, he said to his companion —

“From

here you get a fine view of the stage; steady yourself by the rope and look

down. I’ll be with you in a moment.”

He ran into the dressing-room from

whence the voice proceeded, and

St. John

stepped out upon a little platform, hastily

built for the launching of an aeriel-car in some grand spectacle. Glad to

escape meeting him, I was about to go on, when, from an obscure corner, a dark

figure glided noiselessly to the door and leaned in. I caught a momentary

glimpse of a white extended arm and the glitter of steel, then came a cry of mortal

fear, a heavy fall; and flying swiftly down the gallery the figure disappeared.

With one leap I reached the door, and looked in; the raft hung broken, the

platform was empty. At that instant Keen rushed out, demanding what had

happened, and scarcely knowing what I said, I answered hurriedly,

“The

rope broke and he fell.”

Keen

gave me a strange look, and dashed down stairs. I followed, to find myself in a

horror-stricken crowd, gathered about the piteous object which a moment ago had

been a living man. There was no need to call a surgeon, for that headlong fall

had dashed out life in the drawing of a breath, and nothing remained to do but

to take the poor body tenderly away to such friends as the newly-arrived

stranger possessed. The contrast between the gay crowd rustling before the

curtain and the dreadful scene transpiring behind

it,

was terrible; but the house was filling fast; there was no time for the

indulgence of pity or curiosity, and soon no trace of the accident remained but

the broken rope above, and an ominous damp spot on the newly-washed boards

below. At a word of command from our energetic manager, actors and actresses

were sent away to retouch their pale faces with carmine, to restoring their

startled nerves with any stimulant at hand, and to forget, if possible, the

awesome sight just witnessed.

I

returned to my dressing-room hoping Clotilde had heard nothing of this sad, and

yet for us most fortunate accident, though all the while a vague dread haunted

me, and I feared to see her. Mechanically completing my costume, I looked about

me for the dagger with which poor Juliet was to stab herself, and found that it

was gone. Trying to recollect where I put it, I remembered having it in my hand

just before I went up to have my sword-belt altered; and fancying that I must

have inadvertently taken it with me, I reluctantly retraced my steps. At the

top of the stairs leading to that upper gallery a little white object caught my

eve, and, taking it up, I found it to be a flower. If it had been a burning

coal I should not have dropped it more hastilv than 1 did when I recognized it

was one of a cluster I had left in Clotilde’s room because she loved them. They

were a rare and delicate kind, no one but herself was likely to possess them in

that place, nor was she likelv to have given one away, for my gifts were kept

with jealous care; vet how came it there? And as I asked myself the question,

like an answer returned the remembrance of her face w hen she said, “I shall

remember this.” The darkly-shrouded form was a female figure, the w hite arm a

woman’s, and horrible as was the act, w ho but that sorely- tried and tempted

creature would have committed it. For a moment my heart stood still, then I

indignantly rejected the black thought, and thrusting the flower into my breast

went on mv way, tr\ ing to convince myself that the foreboding fear which

oppressed me was caused by the agitating events of the last half hour. Mv w

eapon was not in the wardrobe-room; and as I returned, wondering w hat I had

done w ith it, I saw’ Keen standing in the little doorw ay with a candle in his

hand. He turned and asked w hat I was looking for. I told him, and explained

why I was searching for it there.

“Here

it is; I found it at the foot of these stairs. It is too sharp tor a

stage-dagger, and w ill do mischief unless you dull it,” he said, adding, as he

pointed to the broken rope, “Lamar, that was cut; I have examined it.”

The

light shone full in my face, and I knew that it changed, as did my voice, for I

thought of Clotilde, and till that fear was at rest resolved to be dumb

concerning w hat I had seen, but I could not repress a shudder as I said,

hastily,

“Don’t

suspect me of anv deviltry, for heaven’s sake. I’ve got to go on in fifteen

minutes, and how can I play unless you let me forget this horrible business.”

“Forget

it then, if you can; I’ll remind you of it to-morrow.” And, with a significant

nod, he walked a wav, leaving behind him a new trial to distract me. I ran to

Clotilde’s room, bent on relieving myself, if possible, of the suspicion that

w'ould return with redoubled pertinacity since the discovery of the dagger,

which I was sure I had not dropped where it was found. When I tapped at her

door, her voice, clear and sweet as ever, answered “Come!” and entering, I

found her ready, but alone. Before I could open my lips she put up her hand as

if to arrest the utterance of some dreadful intelligence.

“Don’t

speak of it; I have heard, and cannot bear a repetition of the horror. I must

forget it till to-morrow, then

— .”

There she stopped

abruptly, for I produced the flower, asking as naturally as I could —

“Did

you give this to anv one?”

“No;

why ask me that?” and she shrunk a little, as I bent to count the blossoms in

the cluster on her breast. I gave her seven; now there were but six, and I

fixed on her a look that betrayed my fear, and mutely demanded its confirmation

or denial. Other eyes she might have evaded or defied, not mine; the traitorous

blood dyed her face, then fading, left it colorless; her eyes wandered and

fell, she clasped her hands imploringly, and threw herself at my feet, crying

in a stifled voice,