Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 20 (17 page)

Read Alcott, Louisa May - SSC 20 Online

Authors: A Double Life (v1.1)

Discovery

of the Poison

From

any other human being the treachery would not have been so base, but from her

it was doubly bitter, for she knew and owned her knowledge of his exceeding

love. “Am I not dying fast enough for her impatience? Could she not w ait a

little, and let me go happy in my ignorance?” he cried within himself,

forgetting in the anguish of that moment the falsehood told her at his bidding,

for the furtherance of another purpose as sinful but less secret than her own.

How time passed he no longer knew' nor cared, as leaning his head upon his

hands, he took counsel with his own unquiet heart, for all the evil passions,

the savage impulses of his nature were aroused, and raged rcbclliously in utter

defiance of the feeble prison that confined them. Like all strong yet selfish

souls, the wrongs he had committed looked to him very light compared w ith

this, and seeing only his own devotion, faith and patience, no vengeance seemed

too heavy for a crime that would defraud him of his poor remnant of unhappy

life. Suddenly he lifted up his head, and on his face was stamped a ruthless,

reckless purpose, which no earthly

pow

er could change

or stay. An awesome smile touched his white lips, and the ominous fierceness

glittered in his eye — for he was listening to a devil that sat whispering in

his heart.

“I

shall have my hour of excitement sooner than I thought,” he said low' to

himself, as he left the room, carrying the vial w ith him. “My last prediction

will be verified, although the victim and the culprit are one, and Evan shall

live to wish that Ursula had died before me.”

An hour later Ursula came to him as he sat gloomily before his

chamber fire, while Marjory stood tempting him to taste the cordial she had

brought.

As if some impassable and unseen abyss already yaw

ned

between them, she gave him neither wifely caress nor

evening greeting, but pausing opposite, said, with an inclination of her

handsome head, which would have seemed a haughty courtesy but for the gentle

coldness of.her tone:

“I

have obeyed the request you sent me, and made ready to receive the friends

whose coming would else have been delayed. Is it your pleasure that I excuse

you to them, or will you join us as you have often done when other invalids

would fear to leave their beds?”

Her

husband looked at her as she spoke, wondering what woman’s whim had led her to

assume a dress rich in itself, but lustreless and sombre as a mourning garb;

its silken darkness relieved only by the gleam of fair arms through folds of

costly lace, and a knot of roses, scarcely whiter than the bosom they adorned.

“Thanks

for your compliance, Ursula. I will come down later in the evening for a moment

to receive congratulations on the restoration promised me. Shall I receive

yours then?”

“No,

now, for now I can wish you a long and happy life, can rejoice that time is given

you to learn a truer faith, and ask you to forgive me if in thought, or word,

or deed I have wronged or wounded you.”

Strangely

sweet and solemn was her voice, and for the first time in many months her old

smile shed its serenest sunshine on her face, touching it with a meeker beauty

than that which it had lost. Her husband shot one glance at her as the last

words left her lips, then veiled the eyes that blazed with sudden scorn and

detestation. His voice was always under his control, and tranquilly it answered

her, while his heart cried out within him:

“I

forgive as I would be forgiven, and trust that the coming years will be to you

all that I desire to have them. Go to your pleasures, Ursula, and let me hear

you singing, whether I am there or here.” “Can I do nothing else for you,

Felix, before I go?” she asked, pausing, as she turned away, as if some

involuntary impulse ruled her.

Stahl smiled a strange smile as he

said,

pointing to the goblet and the minute bottle Marjory

had just placed on the table at his side: “You shall sweeten a bitter draught

for me by mixing it, and I will drink to you when I take it by-and-by.”

His eye was on her now, keen, cold

and steadfast, as she drew near to serve him. He saw the troubled look she

fixed upon the cup, he saw her hand tremble as she poured the one sale drop,

and heard a double meaning in her words:

“This

is the first, I hope it may he the last time that I shall need to pour this

dangerous draught for you.”

She

laid down the nearly emptied vial, replaced the cup and turned to go. But, as

if bent on trying her to the utmost, though each test tortured him, Stahl

arrested her by saving, with an unwonted tremor in his voice, a rebellious

tenderness in his eves:

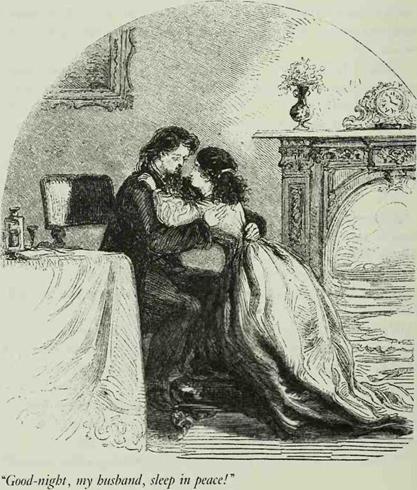

“Stay,

Ursula, I may fall asleep and so not see you until — morning. Bid me

good-night, my wife.”

She

went to him, as if drawn against her will, and for a moment they stood face to

face, looking their last on one another in this life. Then Stahl snatched her

to him with an embrace almost savage in its passionate fervor, and Ursula

kissed him once with the cold lips, that said, without a smile, “Good-night, my

husband,

sleep

in peace!”

“Judas!”

he muttered, as she vanished, leaving him spent with the controlled emotions of

that brief interview. Old Marjory heard the word, and from that involuntary

betrayal seemed to gather courage for a secret which had burned upon her tongue

for two mortal hours. As Stahl sunk again into his cushioned seat, and seemed

about to relapse into his moody reverie, she leaned towards him, saving in a

whisper:

“May

1

tell you something, sir?”

“Concerning

w hat or w hom, my old gossip?” he answ ered, listlessly, yet with even more

than usual kindliness, for now' this humble, faithful creature seemed his only

friend.

“My

mistress, sir,” she said, nodding significantly.

His

face woke then, he sat erect, and w ith an eager gesture bade her speak.

“I’ve

long mistrusted her; for ever since her cousin came she has not been the woman

or the w

ife

she was at first. It’s not tor me to meddle, but it’s clear to see that

if you were gone there’d be a wedding soon.”

Stahl

frowned, eyed her keenlv, seemed to catch some helpful hint from her indignant

countenance, and answered, with a pensive smile:

“I

know it, I forgive it; and am sure that, for my sake, you will be less frank to

others.Ts

this what

you wished to tell me, Marjory?”

“Bless

your unsuspecting heart, I wish it was, sir. I heard her words last night, I

watched her all to-dav, and when she went out at dusk I followed her, and saw

her buy it.”

Stahl

started, as if about to give vent to some sudden passion, but repressed it, and

w ith a look of well-feigned wonder, asked:

“Buy

what?”

Marjory

pointed silently to the

table,

upon w hich lay three

objects, the cup, the little vial and a rose that had fallen from Ursula’s

bosom as she bent to render her husband the small service he had asked of her.

There w

r

as no time to feign horror, grief or doubt, for a paroxysm

of real pain seized him in its gripe, and served him better than any

counterfeit of mental suffering could have done. 1 Ie conquered it by the

pow

er of an inflexible spirit that would not yield yet, and

laying his thin hand on Marjory’s arm, he w hispered, hastily:

“Hush!

Never hint that again, I charge you. I bade her get it, my store was nearly

gone, and I feared I should need it in the night.”

The

old woman read his answer as he meant she should, and laid her withered cheek

down on his hand, saying, with the tearless grief of age:

“Always so loving, generous and faithful!

You may forgive

her, but I never can.”

Neither

spoke for several minutes, then Stahl said:

“I

will lie dow n and try to rest a little before I go

— ”

The

sentence remained unfinished, as, w ith a weary yet wistful

air,

he glanced about the shadowy room, asking, dumbly, “Where?” Then he shook off

the sudden influence of some deeper sentiment than fear that for an instant

thrilled and startled him.

“Leave

me, Marjory, set the door ajar, and let me be alone until I ring.

She

went, and for an hour he lay listening to the steps of gathering guests, the

sound of music, the soft murmur of conversation, and the pleasant stir of life

that filled the house with its social charm, making his solitude doubly deep,

his mood doubly bitter.

Once

Ursula stole in, and finding him apparently asleep, paused for a moment

studying the wan face, with its stirless lids, its damp forehead and its pale

lips, scarcely parted by the fitful breath, then, like a sombre shadow, flitted

from the room again, unconscious that the closed eyes flashed wide to watch her

go.

Presently

there came a sudden hush, and borne on the wings of an entrancing air Ursula’s

voice came floating up to him, like the sweet, soft whisper of some better

angel, imploring him to make a sad life noble by one just and generous action

at its close. No look, no tone, no deed of patience, tenderness or

self-sacrifice of hers but rose before him now, and pleaded for her with the

magic of that unconscious lay. No ardent hope, no fair ambition, no high

purpose of his youth, but came again to show the utter failure of his manhood,

and in the hour darkened by a last temptation his benighted soul groped blindly

for a firmer faith than that which superstition had defrauded of its virtue.

Like many another man, for one short hour Felix Stahl wavered between good and

evil, and like so many a man in whom passion outweighs principle, evil won. As

the magical music ceased, a man’s voice took up the strain, a voice mellow,

strong and clear, singing as if the exultant song were but the outpouring of a

hopeful, happy heart. Like some wild creature wounded suddenly, Stahl leaped

from his couch and stood listening with an aspect which would have appalled the

fair musician and struck the singer dumb.