Alan Turing: The Enigma (59 page)

Read Alan Turing: The Enigma Online

Authors: Andrew Hodges

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology, #Computers, #History, #Mathematics, #History & Philosophy

But even before the first Robinson was finished, Flowers had made a revolutionary proposal which both solved the problem of tape synchronisation, and did away with the laborious production of fresh tapes. The idea was to store the Fish key-patterns

internally

, and in electronic form. If this were done, only one tape would be required. The difficulty lay in the fact that such internal storage would require the more extensive use of electronic valves. It was a suggestion regarded with deep suspicion by the established experts, Keen and Wynn-Williams. But Newman understood and supported Flowers’ initiative.

By any normal standards, this project was a stab in the technological dark. But they were not in normal times, but in the conditions of 1943. What happened next was a development unthinkable even two years before. Flowers simply told Radley, director of the Post Office laboratories, that it was necessary for Bletchley work. Under instructions from Churchill to give Bletchley’s work absolute priority, without questions or delay, Radley had no decision to make, although the development consumed half the resources of his laboratories. Construction began in February 1943 and the machine that Flowers had envisaged was completed after eleven months of night-and-day working. No one but Flowers, Broadhurst and Chandler who together had designed the machine had been permitted to see all the parts, let alone to know what the machine was for. There were no drawings for many of the parts, only the designers’ originals; there were no manuals, no accounts, nor questions asked about materials and labour consumed. In the laboratory the machine was assembled, wired and made to work in separate sections which did not come together until the whole machine was installed and working at Bletchley in December 1943.

In three years, they

had caught up with half a century of technological progress. Dillwyn Knox died in February 1943, passing just before the Italian empire he had done a good deal to undermine, and with him the pre-industrial mind. They had been forced into one scientific revolution by the Enigma, and already they were in the throes of a second. The all-electronic machine proved to be much more reliable than the Robinsons, as well as faster. They called it the

Colossus

, and it demonstrated that the colossal number of 1500 electronic valves, if correctly used, could work together for long periods without error. This was an astonishing fact for those trained in the conventional wisdom. But in 1943 it was possible both to think and do the impossible before breakfast.

Alan knew about all these developments, but declined the invitation to play a direct part.

7

Newman built up an increasingly large and powerful group, drawing in the best talent from the other huts and from the mathematical world outside. Alan moved in the opposite direction; he was not a Newman, skilled in overall direction, and still less was he a Blackett, moving in political circles. He had not fought to retain control of naval Enigma, but had retreated before Hugh Alexander’s organising power. If he had been a quite different person, he could now have made his position one of great influence, it being the time for sitting on coordinating committees, Anglo-American committees, future policy committees. But he had no concern for finding a place in anything but scientific research itself. Other scientists were finding the war to be awarding them a power and influence denied in the 1930s, and thrived upon it. For Alan Turing, the war had certainly brought new experiences and ideas, and the chance to do something. But it had given him no taste for organising other people, and it had left his axioms unchanged. A confirmed solitary, he wanted something of his own again.

It would also take more than the Second World War to change his mother’s ideas, which in December 1943 focussed as always upon the duty of choosing Christmas presents. Alan wrote to her

8

on 23 December:

My dear Mother,

Thank you for your enquiry as to what I should like for Christmas, but really I think we had better have a moratorium this year. I can think of a lot of things I should like which I know to be unobtainable, e.g. a nice chess set to replace the one that was stolen from here while

I was away, and which you gave me in 1922 or so: but I know it is useless to try at present. There is an old set here that I can use till the war is over.

I had a week’s leave fairly recently.

*

Went up to the lakes with Champernowne and stayed in Prof. Pigou’s cottage on Buttermere. I had no idea it was worth while to go amongst the mountains at this time of year, but we had the most marvellous weather, with no rain at all and snow only for a few minutes when we were up on Great Gable. Unfortunately Champernowne caught a chill and retired to bed half-way through. This was in the middle of November, so I don’t think I’ll be taking Christmas leave until February.…

Yours, Alan

But by Christmas 1943, as the

Scharnhorst

was sunk with Enigma help, Alan had set out on a new project, this time something of his own. He handed over his files on American machinery to Gordon Welchman, who left Hut 6 at this point to take on an overall coordinating role. Welchman had lost interest in mathematics, but found a new life in the study of efficient organisation, and was particularly attracted to American liaison. But Alan, since returning from America, had spent a good deal of time on the devising of a new speech encipherment process. And while other mathematicians might be content to

use

electronic equipment, or to know about it in general terms, he was determined to build upon his Bell Labs experience and actually create something that worked with his own hands. In late 1943 he became free to devote time to some experiments.

Speech encipherment was not now regarded as an urgent problem. On 23 July 1943, the X-system had been inaugurated for conversations at top level between London and Washington (the extension to the War Room was not completed for another month). The Chiefs of Staff memorandum

9

of that date stated that ‘The British experts, who were appointed to examine the secrecy [

sic

] of the equipment, have expressed themselves as completely satisfied’; it also listed the twenty-four British top brass, from Churchill downwards, who were allowed to use it, and the forty Americans, from Roosevelt downwards, whom they might call. This solved the problem of high-level Atlantic communications, although it meant that the British had to go cap in hand to use it, and found themselves outdone by the links to the Philippines and Australia that the Americans were busily installing. Nor did they necessarily want to have all their transmissions recorded by the Americans, the alliance never being so close that the British government confided all to the United States. There was every incentive, from the point of view of future policy, to develop an independent British high-grade speech system. It was Britain, not the United States, that was supposed to be the centre of a world political and commercial system.

But this was not undertaken, and nor did Alan’s new idea have the potential for such a development. The principle he had in mind would be

impossible to apply with the variable time-delays and fading experienced with short-wave transatlantic radio transmissions. It would never be the rival of the X-system, which overcame these problems, and this was made clear at the start. It bore the mark of something that he wanted to achieve for himself, rather than of something he had been asked to provide. The war was no longer calling for his original attack on problems, and he found himself almost redundant after 1943. Neither was his idea backed with more than a token share of resources. It was like going back to early, grudging days. To pursue it he had to move to a rather different establishment. While the Bletchley industry continued, with ten thousand people now at work on rolling secrets off the production line, not only deciphering and translating but doing a great deal of the interpretation and appreciation over the heads of the services, Alan Turing gradually transferred himself to nearby Hanslope Park.

While the Government Code and Cypher School had expanded to dimensions quite unimaginable in 1939, the secret service had also mushroomed in a variety of directions. Just before the war, it had recruited Brigadier Richard Gambier-Parry to improve its radio communications. Gambier-Parry, a veteran of the Royal Flying Corps and a genial paternalist to whom junior officers would refer as ‘Pop’, had thereafter spread his wings much further. His first chance had come in May 1941 when the secret service managed to detach from MI5 the Radio Security Service, then responsible for tracking down enemy agents in Britain. It was he who had taken it over. With all such enemy agents soon under control, the role of the RSS had been diverted into that of intercepting enemy agents’ radio transmissions from all over the world. Now known as ‘Special Communications Unit No. 3’, this organisation used a number of large receiving stations centred on the one at Hanslope Park, a large eighteenth century mansion in a remote corner of north Buckinghamshire.

Gambier-Parry had also acquired the responsibility for other aspects of secret service work. These included providing the transmitters for the black broadcasting organisation, which began its ‘Soldatensender Calais’ broadcasts on 24 October 1943. (The studios where journalists and German exiles concocted their ingenious falsities were at Simpson, another Buckinghamshire village.) SCU3 had further taken under its wing the manufacture of the cryptographic system Rockex, which was to be used for top-grade British telegraph signals. Such traffic now amounted to a million words a day to America alone – pre-eminently, of course, carrying Bletchley’s productions. The Rockex represented a technical improvement to the Vernam one-time teleprinter cipher system.

One problem with the Vernam principle was that the cipher-text, regarded as a teleprinter input in the Baudot code, was bound to include many occurrences of the operational or ‘stunt’ symbols, those which produced not letters but ‘line feed’, ‘carriage return’ and so forth. For this reason, the cipher-text could not be handed over to a commercial telegraph company for transmission in Morse, as was often desirable. It was Professor Bayly, the Canadian engineer at Stephenson’s organisation in New York,

*

who had devised a method of suppressing the unwanted characters and replacing them in such a way that the resulting cipher-text could be printed neatly on a page. This required the development of electronics which could automatically ‘recognise’ the unwanted telegraph symbols. The problem involved logical circuits such as appeared in the Colossus, albeit on a much more modest scale, using electronic switching for Boolean operations applied to the holes of telegraph tape.

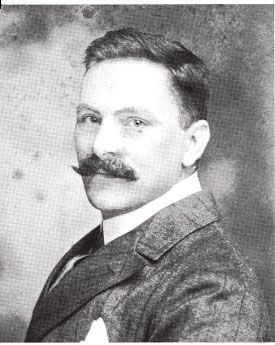

Alan’s father, Julius Turing, in about 1907.

On the beach: Alan and his brother John at St Leonard’s in 1917.

On the cliffs: Alan and his mother at St Lunaire, Brittany, in 1921 (see page 10).