After Tamerlane (27 page)

Authors: John Darwin

It was some time before the full effects were felt. But losing the Crimea was a strategic catastrophe for the Ottomans. Until then the Black Sea had been a Turkish lake, part of the Ottomans' imperial communications. With a monopoly of power on its waters, they could guard the northern approaches to their empire with remarkable ease. Without seaborne supplies a Russian invasion into the Ottoman Balkans was difficult if not impossible, as Peter the Great had found. On the other side of the Black Sea, an advance into the Caucasus along the western edge of its mountain chain was even more arduous without maritime support. The Black Sea was the naval shield of the Ottoman system. It narrowed the strategic frontier which the Ottomans had to guard against their European enemy. Invasion must come through the western Balkans â an inhospitable region, where all the advantage lay with the defence. It reduced their great-power rivals effectively to one â the Habsburg Empire, with which they shared a border. It allowed the Ottoman navy to concentrate in the eastern Mediterranean, where it could guard the Aegean Islands, the approach to Constantinople and the shores of Egypt and the Levant with little to fear from the faraway naval powers of Europe â Britain, France, the Netherlands and Spain. Most of all, perhaps, the strategic benefit of the Black Sea was felt politically. The security it gave had permitted the decentralization of power in the Ottoman realm, a vital ingredient of its stability and cohesion in the eighteenth century.

With the sea gate to the north wedged shut, the Ottoman government in Constantinople had weathered the storms of the earlier eighteenth century. The Ottomans' prestige as imperial rulers had been battered, but not broken. Their value as allies in the Machiavellian game of European diplomacy had been real. But in the 1780s the keystone of Ottoman power was torn out. The effects were magnified by the decline of France. A new resurgence began in the Christian communities in Greece and in the northern Balkans. Almost imperceptibly, the empire began to change from a great power of acknowledged (if resented) strength into a region of contestation, a vast territorial prey round which a whole pack of European predators began to circle.

This transformation into the âSick Man of Europe' was, however, mainly a feature of the second phase of the geopolitical revolution after 1790. But long before that the effects were being felt of the other

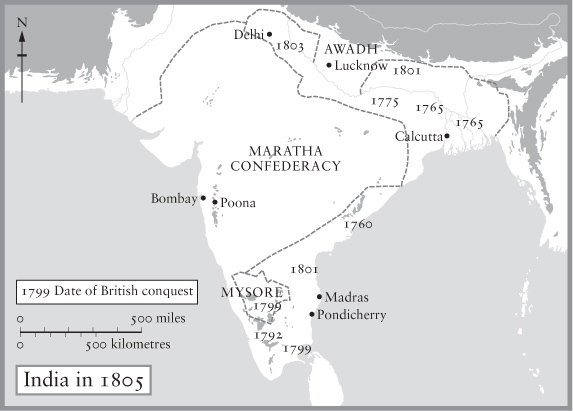

great centre of geopolitical turbulence in eighteenth-century Eurasia. In the last chapter we saw how by the early 1750s a âdouble revolution' was under way in India. The old shell of the Mughal Empire, which had provided a framework of political unity for much of the subcontinent, was being cracked. In the inland heart of the empire, Mughal power was assaulted from two sides. Iranian and then Afghan adventurers pursued the old Inner Asian tradition of empire-building using the âtribal' manpower of Inner Asia to impose their rule on the agrarian plains â just as the Mughals had done before them (or the Manchus in China). Their aim may have been to control the commercial traffic between northern India and Central Asia, still one of the world's great trade routes. Their attacks coincided with the decisive advance of Maratha power in western India: a Hindu confederacy of âgentry' states bent on extending its rule and land-revenue system into the Mughal heartland on the North Indian plains.

18

Under the stress of social and economic, as well as political, change, Mughal power was breaking down (or mutating) into a looser regime, coexisting with the new âsub-empires' scrambling for territory, trade and revenue. In maritime India there was a similar threat. Here the agent of change was the rapid expansion of the commercial economy and overseas trade. New wealth and new revenues gave regional sub-rulers more and more freedom from Mughal supervision, and made them less and less willing to pay the tribute they owed. But this growing autonomy came with a price. Would-be state-builders had to keep a close watch on the merchants and bankers who funded their power â and to keep a sharp eye on the European interests who had tightened their grip on India's overseas commerce. This was all the more vital when the Europeans showed signs of importing their quarrels into the Indian subcontinent. Getting themselves ready to fight

each other

turned the French and British into local military powers, and injected an explosive new element into a volatile political scene.

The main theatre of conflict was found in Bengal, the most dynamic and prosperous of the coastal economies. Here a vast output of cotton textile production had sprung up to meet a soaring world market. The riverine network of the Ganges and its delta and the foodstuffs grown in the newly cleared forests were the vital ancillaries of this export economy. Political power was in the hands of the

subahdar

â

formally the viceroy of the Mughal emperor â and his fellow Muslim magnates: the expectant legatees of Mughal decline. But stability was elusive in this parvenu world. In 1756 the

subahdar

, or nawab, Suraj ud-Daula was a new and nervous incumbent. He had political rivals. The financial power of Hindu merchants and bankers, such as the great Jagat Seth, checked his freedom of action: they managed the trade on which rents and revenue depended. They were closely connected with the European traders, especially the English East India Company with its fortified âfactory' at Calcutta â âa large irregular place, something bigger than Deptford and Rotherhithe' is a contemporary description

19

â and its theoretical freedom (with its imperial

farman

) from the nawab's control. When the nawab suspected that the Company was sheltering those plotting against him, Bengal's jittery politics were plunged into crisis. The Company's refusal to yield brought a trial of strength.

20

In June 1756, the nawab seized Calcutta, and the Company officials who failed to escape were thrown into jail (the famous âBlack Hole'). For a moment it seemed as if this

coup d'état

signalled the rise of a new South Asian mercantilist state â an oriental Netherlands that could hold its own.

Suraj ud-Daula's misfortune was that the Company had the means to retaliate. It had a powerful motive for revenge: the loss of Calcutta had cost it more than £ 2 million. Six months later a squadron of ships arrived in the Ganges bringing troops from Madras under Robert Clive. Clive quickly recovered Calcutta and made contact with the dissident magnates eager to see the nawab brought down. After Clive's show of force at Plassey near the Bengal capital in June 1757, the nawab's army broke up and his rule collapsed. Clive was now the kingmaker. âA revolution has been effectedâ¦', Clive told his father, âscarcely to be paralleled in history.'

21

But Clive was reluctant to assert the Company's rule in Bengal. âSo large a sovereignty may possibly be an object too extensive for a mercantile company⦠without the nation's assistance,' he thought.

22

Instead it seemed wiser to install a Muslim noble as the new nawab. The experiment failed. The Company servants, pursuing their private trade, refused to acknowledge the nawab's authority or pay the duties they owed him. By 1764, friction had boiled over into armed struggle. At the Battle of Buxar, the Company army defeated the nawab and his ally, the ruler of Awadh.

The following year, the Company took on the diwani for Bengal, Bihar and Orissa: now it, not the nawab, controlled the taxes and revenue â âNothing remains to [the nawab] but the name and shadow of authority.'

23

These events were astonishing. But the revolution in India was far from complete. Clive himself was fearful of overstraining the Company's power, and resisted the idea of a march to Delhi. The British were not the sole beneficiaries of Indian change. In the west and centre of the subcontinent, the remorseless rise of Maratha power seemed just as impressive. In 1784 it was the Marathas who took Delhi. In the south of India, Hyderabad and Mysore showed that new states could be built from the debris of Mughal decline. In Mysore, especially, a Muslim soldier of fortune, Haidar Ali, began after 1761 to construct a new-style fiscal-military state, with a revenue and an army that was more than a match for the Company at Madras. Under his son Tipu Sultan (r. 1783â99), these changes were carried much further. The state practised trade, subsidized shipbuilding, and funded a large standing army with artillery and infantry whose training and tactics were as âmodern' as the Company's.

24

Haidar and Tipu fought wars of attrition against the Company's influence and brought it to the verge of financial collapse. Without the resources it had seized in Bengal, with which it built up its armies from

18,000

men in

1763

to more than 150,000 by the end of the century,

25

without naval and military help from Britain, and without the loans advanced by Indian bankers, it is doubtful whether the Company would have retained its power in South India. And, though they defeated (and killed) Tipu in 1799, it is equally doubtful whether the British could have forced the Marathas to acknowledge their rule had they not been triumphant in the second great phase of European conflict to which we will turn in a moment. By the 1790s, indeed, the two main theatres of Eurasia's geopolitical upheaval had all but fused into one.

Already, however, Clive's Bengal revolution was beginning to lever an even more remarkable shift in Eurasian relations. Long before Europeans had entered the Indian Ocean, maritime India had served as the hinge between the trade of East Asia and that of the Middle East and the West. In the eighteenth century, Europeans had increased their commerce with China, strictly confined though it was to brief

visits on sufferance to the port of Canton. The English East India Company dominated this trade, carrying mainly bullion to China in exchange (mainly) for tea, the growing craze of the British consumer.

But it lacked the means to expand the traffic, extend more generous credit, or attract Chinese customers with more tempting products. The conquest of Bengal solved all three problems. With its new revenue stream, the Company could pay for the Indian produce that Chinese purchasers wanted â raw cotton, cotton textiles and opium â without resorting to silver or sending more exports to India. But the Company's means were only part of the story. Of growing importance was the âprivate trade', tolerated by the Company for its own convenience. A small army of Europeans â soldiers and civilians employed by the Company in India â exploited its rise to make fortunes from plunder or privileged trade. (These were the ânabobs', whose return to Britain roused much hostile comment.) The most profitable way to remit their winnings was to invest in a cargo to be sent to China.

When it was sold, the credit it earned was given to the Company (which held the monopoly for the purchase of tea) in exchange for a claim on sterling in London. Private trade was also the medium through which opium was sold, since the Company itself was forbidden to trade in it. In this roundabout way, the conquest of Bengal opened the way for a commercial revolution with huge geopolitical consequences.

26

As its exports grew by leaps and bounds, the economy of South China was drawn deeper and deeper into the triangular trade between Britain and India. The biggest fish of all was beginning to be hooked.

Geopolitical change in Europe and South Asia thus opened the way for a huge transformation in the relations between different parts of Eurasia, and between Eurasia and the Outer World. In the second phase, after 1790, the full extent of this shift became gradually clearer and the glimmering outlines of a new global order, faintly observable in the late eighteenth century, assumed a definite shape. But this happened only after a second eruption in European politics, and a new global war, had settled the question of which power, if any, would dominate Europe, and which would be free to take the path to world power.

The crisis was sparked by the revolution in France. The Bourbon state had become increasingly brittle. It lacked popular backing; its aristocratic and middle-class allies were more and more discontented; its intellectual and cultural prestige had been sapped by the pamphlet war of the

philosophes

and the earthier onslaught of popular writers. These were not unusual weaknesses in an eighteenth-century dynastic state. âAt present every power is in a state of crisis,' wrote the tsarina Catherine the Great in 1780.

27

What made them so dangerous to the Bourbon regime was the simultaneous collapse of its historic role as the guardian of French greatness in Europe and the world. By the late 1780s the âgrand nation' of Europe had lost its pre-eminence. For the monarchy's prestige this was bad enough. But the immediate danger was a financial breakdown. After a brief period of peace, France had gone to war in 1778 to reverse the verdict of 1763 and restore its Atlantic position in alliance with Britain's rebellious colonies. It was an expensive gamble, and yielded little. The price was a further accumulation of debts. It was true that the French public debt was

smaller than Britain's. The critical fact was that it was far harder to manage, and far more expensive. On the eve of the revolution, just paying the interest consumed half the state's spending.

28

In 1789, with its prestige at a nadir, and its treasury bankrupt, the monarchy fell into the maelstrom of constitutional change, ceding effective political power to the self-proclaimed leaders of the âThird Estate', reconstituted in June as the âNational Assembly'. As financial chaos grew deeper and social order unravelled, the threat of foreign intervention by the conservative powers, headed by Austria, loomed larger and larger. Fear that the king was conspiring with them to tear up the constitution he had signed in September 1791 radicalized French politics. By the spring of 1792 France was at war with Austria. Military disaster and the popular fear of invasion destroyed the influence of more moderate reformers and brought the monarchy's abolition in September 1792.

29

When Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed in January 1793, France's transformation was complete. The pillar of the

ancien régime

in Europe, the archetype of the dynastic state, had become a militant revolutionary republic, bent on exporting its subversive doctrine of the âRights of Man'.