After Tamerlane (2 page)

Authors: John Darwin

Ch'ien-lung

not

Qianlong

Kuomintang

not

Guomindang

Chiang Kai-shek

not

Jiang Jeshi

Mao Tse-tung

not

Mao Zedong

Chou En-lai

not

Zhou Enlai

Orientations

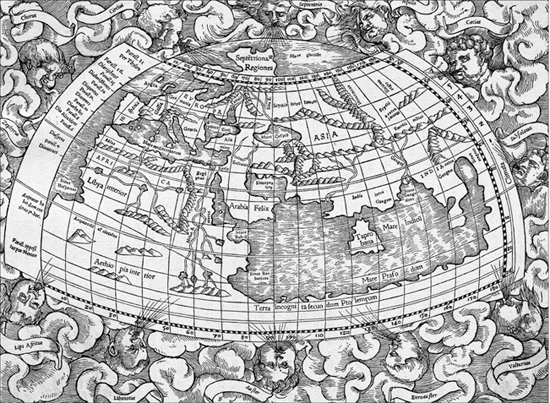

1. Ptolemy's map of the world, the basis of European knowledge until the late fifteenth century

In 1401 the great Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun (1332â1406) was in the city of Damascus, then under siege by the mighty Tamerlane. Eager to meet the famous conqueror of the day, he was lowered from the walls in a basket and received in Tamerlane's camp. There he had a series of conversations with a ruler he described (in his autobiography) as âone of the greatest and mightiest of kings⦠addicted to debate and argument about what he knows and does not know'.

1

Ibn Khaldun may have seen in Tamerlane the saviour of the ArabâMuslim civilization for whose survival he feared. But four years later Tamerlane died on the road to China, whose conquest he had planned.

Tamerlane (sometimes Timur, or Timurlenk, âTimur the Lame' â hence his European name) was a phenomenon who became a legend. He was born, probably in the 1330s, into a lesser clan of the Turkic-Mongol tribal confederation the Chagatai, one of the four great divisions into which the Mongol empire of Genghis (Chinggis) Khan had been split up at his death, in 1227. By 1370 he had made himself master of the Chagatai. Between 1380 and 1390 he embarked upon the conquest of Iran, Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), Armenia and Georgia. In 1390 he invaded the Russian lands, returning a few years later to wreck the capital of the Golden Horde, the Mongol regime in modern South Russia. In 1398 he led a vast plundering raid into North India, crushing its Muslim rulers and demolishing Delhi. Then in 1400 he returned to the Middle East to capture Aleppo and Damascus (Ibn Khaldun escaped its massacre), before defeating and capturing the Ottoman sultan Bayazet at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. It was only after that that he turned east on his final and abortive campaign.

Despite his reputation as a bloodthirsty tyrant, and the undoubted savagery of his predatory conquests, Tamerlane was a transitional figure in Eurasian history.

2

His conquests were an echo of the great Mongol empire forged by Genghis Khan and his sons. That empire had extended from modern Iran to China, and as far north as Moscow.

It had encouraged a remarkable movement of people, trade and ideas around the waist of Eurasia, along the great grassy corridor of steppe, and Mongol rule may have served as the catalyst for commercial and intellectual change in an age of general economic expansion.

3

The Mongols even permitted the visits of West European emissaries hoping to build an anti-Muslim alliance and win Christian converts. But by the early fourteenth century the effort to preserve a grand imperial confederation had all but collapsed. The internecine wars between the âIlkhanate' rulers in Iran, the Golden Horde and the Chagatai, and the fall of the Yuan in China (by 1368), marked the end of the Mongol experiment in Eurasian empire.

Tamerlane's conquests were partly an effort to retrieve this lost empire. But his methods were different. Much of his warfare seemed mainly designed to wreck any rivals for control of the great trunk road of Eurasian commerce, on whose profits his empire was built. Also, his power was pivoted more on command of the âsown' than on mastery of the steppe: his armies were made up not just of mounted bowmen (the classic Mongol formula), but of infantry, artillery, heavy cavalry and even an elephant corps. His system of rule was a form of absolutism, in which the loyalty of his tribal followers was balanced against the devotion of his urban and agrarian subjects. Tamerlane claimed also to be the âShadow of God' (among his many titles), wreaking vengeance upon the betrayers and backsliders of the Islamic faith. Into his chosen imperial capital at Samarkand, close to his birthplace, he poured the booty of his conquests, and there he fashioned the architectural monuments that proclaimed the splendour of his reign. The âTimurid' model was to have a lasting influence upon the idea of empire across the whole breadth of Middle Eurasia.

But, despite his ferocity, his military genius and his shrewd adaptation of tribal politics to his imperial purpose, Tamerlane's system fell apart at his death. As he himself may have grasped intuitively, it was no longer possible to rule the sown from the steppe and build a Eurasian empire on the old foundations of Mongol military power. The Ottomans, the Mamluk state in Egypt and Syria, the Muslim sultanate in northern India, and above all China were too resilient to be swept away by his lightning campaigns. Indeed Tamerlane's death marked in several ways the end of a long phase in global history. His

empire was the last real attempt to challenge the partition of Eurasia between the states of the Far West, Islamic Middle Eurasia and Confucian East Asia. Secondly, his political experiments and ultimate failure revealed that power had begun to shift back decisively from the nomad empires to the settled states. Thirdly, the collateral damage that Tamerlane inflicted on Middle Eurasia, and the disproportionate influence that tribal societies continued to wield there, helped (if only gradually) to tilt the Old World's balance in favour of the Far East and Far West, at the expense of the centre. Lastly, his passing coincided with the first signs of a change in the existing pattern of long-distance trade, the EastâWest route that he had fought to control. Within a few decades of his death, the idea of a world empire ruled from Samarkand had become fantastic. The discovery of the sea as a global commons offering maritime access to every part of the world transformed the economics and geopolitics of empire. It was to take three centuries before that new world order became plainly visible. But after Tamerlane no world-conqueror arose to dominate Eurasia, and Tamerlane's Eurasia no longer encompassed almost all the known world.

In this book we traverse a vast historical landscape in pursuit of three themes. The first is the growth of global âconnectedness' into the intensified form that we call âglobalization'. The second is the part that was played in this process by the power of Europe (and later the âWest') and through the means of empire. The third is the resilience of many of Eurasia's other states and cultures in the face of Europe's expansion. Each of these factors has played a critical part in shaping the world that became by the twentieth century a vast semi-unified system of economics and politics, a common arena from which no state, society, economy or culture was able to remain entirely aloof.

No matter how detailed the subject or obscure the topic, histories are written to help to explain how we got where we are. Of course, historians often disagree with each other's accounts, and one of the reasons is the conflict of opinion about the nature of the âpresent' â

the end product of history. To add to the difficulty, we constantly change our view of the present and âupdate' it in line with unfolding eventsârevising as we do so the questions we ask of the past. But for the moment at least it is widely acknowledged that we live in an age that is strikingly different in many essentials from the world as it was a generation ago â before 1980. In ordinary language, we sum up the features that have been most influential in a catch-all term: âglobalization'. Globalization is an ambiguous word. It sounds like a process, but we often use it to describe a state â the terminal point after a period of change. All the signs are that, in economic relations at least, the pace of change in the world (in the distribution of wealth and productive activity between different regions and continents) is likely to grow. But we can, nonetheless, sketch the general features of the âglobalized world' â the stage which globalization has now reached â in a recognizable form. This is the âpresent' whose unpredictable making the history in this book attempts to explain.

These features can be briefly summarized as follows:

1. the appearance of a single global market â not for all but for most widely used products, and also for the supply of capital, credit and financial services;

2. the intense interaction between states that may be geographically very distant but whose interests (even in the case of very small states) have become global, not regional;

3. the deep penetration of most cultures by globally organized media, whose commercial and cultural messages (especially through the language of âbrands') have become almost inseparable;

4. the huge scale of migrations and diasporas (forced and free), creating networks and connections that rival the impact of the great European out-migration of the nineteenth century or the Atlantic slave trade;

5. the emergence from the wreck of the âbipolar age' (1945â89) of a single âhyperpower', whose economic and military strength, in relation to all other states, has had no parallel in modern world history;

6. the dramatic resurgence of China and India as manufacturing powers. In hugely increasing world output and shifting the balance

of the world economy, the economic mobilization of their vast populations (1.3 billion and 1 billion respectively) has been likened to the opening of vast new lands in the nineteenth century.

This list ought to provoke a series of questions. Why, in a globalized world, should one state have attained such exceptional power? Why has the economic revival of China and India been such a recent development? Why until recently have the countries of the West (now including Japan) enjoyed such a long lead in technological skills and in their standards of living? Why do the products of Westernized culture (in science, medicine, literature and the arts) still command for the most part the highest prestige? Why does the international states system, with its laws and norms, reflect the concepts and practice of European statecraft, and territorial formatting on the European model? The globalized world of the late twentieth century was not the predictable outcome of a global free market. Nor could we deduce it from the state of the world five centuries ago. It was the product of a long, confused and often violent history, of sudden reversals of fortune and unexpected defeats. Its roots stretch back (so it is widely believed) to the âAge of Discovery' â back, indeed, to the death of Tamerlane.

Of course, there have been numerous theories and histories without number explaining and debating the course of world history. The history (and prehistory) of globalization has always been controversial. Since most of the features of globalization seemed closely related to the growth of European (later Western) predominance, it could hardly be otherwise. The lines of battle were drawn up early on. Among the first to imagine a globalized world were the British free-traders of the 1830s and '40s, who drew their inspiration from Adam Smith. Worldwide free trade, so they reasoned, would make war unthinkable. If every country depended upon foreign suppliers and customers, the web of mutual dependence would be too strong to break. Warrior aristocracies that thrived in a climate of conflict would become obsolete. The bourgeois ideal of representative government, spread by traders and trade, would become universal. This cheerful account of how enlightened self-interest would remake the world to the profit of all was punctured by Karl Marx. Marx insisted

that, sooner or later (he expected it to be sooner), industrial capitalism would drown its markets in goods. It could survive for a while by cutting its costs, driving wages below the cost of subsistence. But when the workers revolted â as revolt they must â capitalism would implode and the proletariat would rule. The world beyond Europe would be caught up in the struggle. In their hunger for markets, the European capitalists were bound to invade Asia (Marx's example was India) and wreck its pre-modern economies. The Indian weaver would go to the wall for the sake of Lancashire profits. India's village system and its social order were âdisappearing not so much through the brutal interference of the British tax-gatherer and⦠soldier, as [through] the working of English steam and English free trade'.

4

The saving grace of this work of destruction was its unintended consequence. It would bring a social revolution to Asia, without which (so Marx implied) the rest of the world would not reach its socialist destiny.

Marx had argued that a global economy would grow out of Europe's demands. Lenin insisted that capitalism depended upon economic imperialism, and predicted its downfall in a global revolt of colonial peoples.

5

The MarxâLenin version, half-history, half-prophecy, seemed the key to world history. From the 1920s onward it exerted huge intellectual influence. It saw Europe's economic expansion as the irresistible force ruling the rest of the world. But, instead of creating the bourgeois utopia promised by the British free-traders, it had divided the world. The capitalist-industrial zone that was centred in Europe (and its American offspring) had become richer and richer. But across the rest of the globe, colonial subjection or semi-colonial dependence brought growing impoverishment. Capitalist wealth and Europe's imperial power had combined to enforce a grossly unequal bargain. âFree' trade had been used in the non-Western world to destroy old artisan industries, block industrial growth, and lock local economies into producing cheap raw materials. Indeed, because those raw materials would get steadily cheaper than the industrial goods for which they were meant to pay (or so ran the argument), poverty and dependence could only get worse, unless and until the âworld system' they sprang from was demolished by force.

6