Aches & Pains (7 page)

Authors: Maeve Binchy

Then one day, when I was about twenty-two, I went to a wedding. The bride and groom were an extremely handsome couple. They could have been sent over by Central Casting so much did they look the part.

And as we all followed them glumly out of the church I caught sight of my reflection in a glass door.

Now I hadn’t any great illusions about the way I looked. I was wearing a suit belonging to my mother which hadn’t looked great on her either, and it had been bundled up in the bicycle shed of the school where I taught.

Why was this, you ask? So I could change into it after I had complained of not feeling well so I could get off my Saturday morning teaching to go to the

wedding. I’d also gone to the wedding on the bus without the benefit of a mirror to indicate the unusual shape and angle of a very old hat.

‘I look desperate,’ I said to a woman beside me.

‘I know you do,’ she said reassuringly. ‘So do I. I can’t wait to get into the drink to make me forget it.’

‘Will drink make me forget what I look like?’ I asked innocently, and began life as a drinker.

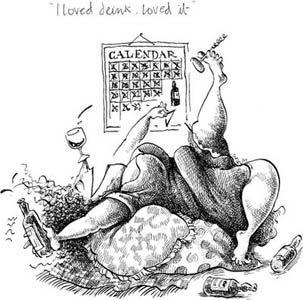

I loved drink. Loved it. And I may be wrong but I don’t think it turned me into a Jekyll and Hyde. I was just rather louder and even more insanely talkative and cheerful than the norm. I forgot things, of course, and had hangovers and stayed on much too late in places. But what the hell.

And amazingly my liver held out and I didn’t lose my job or house or my friends over it. But one day when I couldn’t walk or stand or lie down, and most important of all couldn’t sleep with arthritis, it was put to me rather plainly that if I were even to think about a new hip then a great deal of weight would have to be lost. And drink, however jolly, and to my mind it is very jolly, is a great enemy of weight loss. It looked, sadly, as if we were into extremes again.

AN INSPIRING STORY

I had a great plan. I would drink one day a month. Every single month there would be an Evening with

Wine. I would plan this carefully for about thirty days.

And I did. The actual outings themselves were fairly spectacular because they were so eagerly anticipated.

In January I went to an Italian restaurant on my wedding anniversary and after two glasses of wine became helpless and incapable with drink and tears. I sobbed to the whole clientele, and eventually to the kitchen staff who came out to know what was happening, how very, very happy I was. I apparently listed all the shortcomings of the people I hadn’t married. It took three days to get over that.

In February I had one glass of a very full-bodied red wine in South Africa and more or less passed out until I was assisted to the taxi.

In March I unwisely drank some champagne on a flight to Chicago and fought bitterly with the air stewardess who was going to marry a man she didn’t love. I was so depressed by her attitude to things, I brooded too much about it and fell out of bed, breaking my nose and my toe.

In April I was so ashamed of what had happened in March I had no evening at all with wine.

In May it was my birthday so I had an Evening with Wine surrounded by cushions and rugs in case I fell again.

And then in June I had lost the weight and I got the new hip.

Now I know all this sounds very extreme and possibly not at all helpful to normal people. But

there just might be a few extreme folk looking at this book who will be helped, which is why I decided to share my inspiring if somewhat overly-dramatic tale.

I have an Evening with Wine once a week now, which isn’t nearly as nice as an Evening with Wine every night. But it’s four times better than once a month.

GIVING UP DRINK

1) You feel heroic.

2) Your liver turns nice and pink again.

3) You won’t have to explain. Only the worst kind of bore begs you to ‘have just one’ these days. Mostly, people actually don’t notice if you’re drinking or not. Trust me on this, it surprised me too.

4) You don’t have hangovers.

5) You save money.

6) You remember what happened.

7) You get more work done.

8) You won’t find it nearly as bad as you think. Anticipating a dry evening is much worse than actually having one, and no wine is easier than a little wine. Trust me on this too.

9) You don’t get that that sudden urge to eat everything that’s on the table.

10) You have a load of great help out there if this advice isn’t quite enough for you.

BED THAT WILL ENSURE YOU GET

NO MORE VISITS

‘I thought you were never going to get here.’

‘Oh, it’s you again, is it?’

‘Well, how do you think I am, stuck in here?’

‘Not more fruit, I’ll turn into an orange at this rate.’

‘I hope you’re keeping the place properly at home.’

‘I’ve read that, you can take it home with you.’

‘They say I’m getting better, but what do they know?’

‘It’s easy for you, you can walk away on your own two good legs.’

‘You’ll never guess what my last visitor brought me …’

‘You can go now if you want to.’

WHERE THINGS ARE‘You mean you’re going already?’

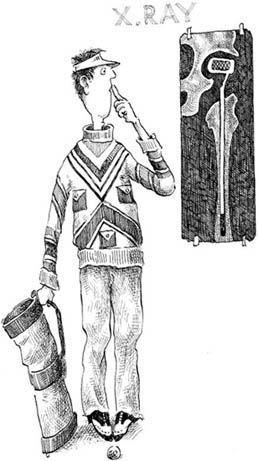

I used to think the kidneys were somewhere in the knickers area. But they’re not. They are up behind your bra strap, if you are the sex and shape that wears a bra. If not you still know where I mean.

Get a map of arteries. They look like an amazing underground rail system. We might clog them and fur them a bit less if we knew what they look like.

Be courageous and look at a picture of the large intestine and the small one. Why should we come over all silly and squeamish about how bits of us look if we expect medical people to take them in their stride?

Examine a picture of a skeleton and see whether the knee bone is actually connected to the thigh bone, etc. or if it’s only a song.

If a real medical text on all this is too much for you, get a child’s book on the body. The basics are there but presented much more cheerfully.

And why not take a mirror and look into your own orifices? You look into totally unimportant things like other people’s windows, open handbags, shopping trolleys in a supermarket. You won’t tremble so much about an ear, nose, throat or indeed any other aperture, if you have examined it in good health.

ONE ADDICT’S STORY

If there was an easy way to give up smoking, I feel pretty sure we would have heard of it by now. In the meantime, there is some research to show that reading other people’s stories of renunciation actually paves the way. Here’s mine.

I got the whole way through school and college without smoking. And this was despite growing up in a home where most around me were wheezing and

inhaling and gasping and either complaining about the cost of cigarettes if they were old enough to buy them or unravelling butts in ashtrays if they weren’t.

My friends all smoked and they never once congratulated me on my strength. They just said Maeve was useless because she never had five zipped away in the back of a bag like other nicer people did. I had nothing to offer in a crisis and no way of being calmed down myself by others if the crisis was in my court.

And then one fateful day a particularly horrible acquaintance inhaled through her slim body right down to her tiny feet and told me I was very brave not to smoke.

Brave?

Yes, apparently. Because if I had been smoking, I wouldn’t have been eating a warm almond bun covered with butter.

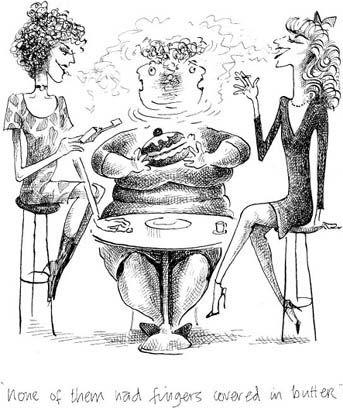

I looked around the group. They were frighteningly elegant. They even made smoke rings, some of them. None of them had fingers covered in butter, none of their eyes were looking at the last almond bun on the plate.

We had all been to a film where Humphrey Bogart and Lauren or Ingrid or some other non-almond-bun-eating person had looked just terrific.

A grown-up sensible woman of twenty-two, earning my own living, not a pre-teen racked with insecurity, I can still hear myself saying to the horrible acquaintance that I’d give it a try.

That was in 1962. For the next sixteen years nobody saw me much, because I was behind a thick wall of smoke. I suppose I didn’t eat as many almond buns as I had, but it didn’t really matter since I was hardly visible.