Aches & Pains (2 page)

Authors: Maeve Binchy

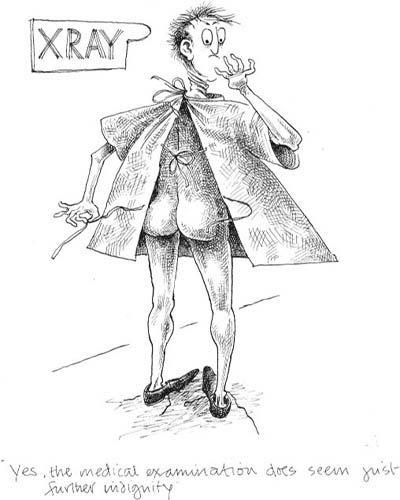

BARING YOUR BODY

Did anyone ever say that going for a medical examination is somehow in the same league as entering a beauty competition?

Yet nurses say they are driven mad by time-wasting false modesty, and insanely apologetic attitudes about what is, after all, just a human body. Although sympathetic and aware of how low some people’s self-esteem can be, particularly at a time of ill health, medical staff say they often wish there was some kind of basic training course for patients, something to convince them that this is not an exhibition or a peep show. It’s an attempt to find out what is wrong with them and cure it.

They report patients who clutch onto hospital gowns when asked to remove them, as if the staff were just about to play the music and ask them to do the Full Monty for the X-ray department. Many women tense up at the thought that people may be studying their stretch marks or odd stomach flaps and reporting their deeply unsatisfactory findings all over the city.

But when a man is asked to take off his shirt so that someone with a stethoscope can listen to his lungs, that’s what they are actually doing, listening to his lungs. They are not measuring him up as an understudy for Schwarzenegger, or checking out his swelling biceps and manly shoulders, and finding him wanting.

When a woman removes her clothes to place her breast into the contraption that will deliver a mammogram she is not being auditioned for a

Playboy

centrefold, she is wisely getting herself tested for pre-cancerous cells.

A man who suspects he may have a prostate or hernia problem cannot be examined for either while in his city clothes. A woman can hardly have a smear test while wearing the baggy leggings of her pink track suit.

Yes, the medical examination does seem just one further indignity, inviting humiliation and vulnerability, at the very time when it’s least tolerable. None of us would choose to have to show to complete strangers the parts of ourselves that most other human eyes don’t reach. But they have seen all those bits of people before. In fact they are seeing such bits all day long.

When we realise that self-consciousness is self-obsessiveness, it’s much easier to take off our clothes as quickly as possible and get whatever it is done.

I speak from the point of view of someone not at all satisfied with a body image, but lucky enough to know it’s of no interest to anyone on earth except myself. I was helped by a happy childhood where we were all told we looked great and believed it, and by good friends along the way who were never part of any style police.

But I think I was also greatly helped by going to a nudist colony by accident. I was going as a journalist to write about it, and I turned up on the bus with

my clothes on, intending to leave them on. But the bus went, and either I took my clothes off or I sat on the side of the road for eight hours until another bus came back to find me. It was in Yugoslavia and it was very hot. I took my clothes off.

I went into the camp and hid behind a bush. Then I crept out a bit and sat sort of covering myself with my handbag on my lap and my arms across my chest, smoking in a frenzy.

And then slowly I noticed people with the most horrific shapes and dangling bits and extraordinary appendages going by, and nobody was paying a blind bit of notice. So I got the courage to slink along the wall towards the restaurant.

I joined the regular campers, and we sat in cafés all day with bits of us falling into the soup, and our bottoms roasting on hot seats. Occasionally we fell into the sea without having to put on or take off swimming costumes. And eventually my eyes stopped looking at the white bits of people and I just got on with the day like everyone else.

It was about the most liberating thing I ever did. I would wish the same sense of freedom to all those I see covering themselves and refusing to come out from behind screens. Who do they think is running some kind of check on them? Why do they think their individual bodies would be of such interest to other people? And that’s only in Out-Patients. By the time you get them into a hospital bed there’s a whole new set of neuroses.

A lot of these are bedpan-orientated. Again, it’s

only natural to be slightly embarrassed that what is usually done in the privacy of a bathroom has to be done in a container in bed and the results removed by someone else.

I made official enquiries about what was the very best thing patients could do about this from a nurse’s point of view. The answer was unanimous. They didn’t want any theatrics over the bedpan. It was part of their work, people who couldn’t move from bed had to have them.

Politeness was always acceptable, and nurses like everyone else always appreciated a word of thanks. But apologies were out of place. It was like trying to deny bodily functions, which was idiotic. As one nurse said very succinctly to me when, like everyone, I apologised for having to use a bedpan, ‘Look at it this way, Maeve, if I weren’t washing your bottom I’d be washing someone else’s’. Which indeed was undeniable.

I’ve found six non-alcoholic drinks that taste fine just as long as you don’t think they are anything other than what they are. The whole secret is not trying anything that pretends to taste remotely like a real drink.

1) Chilled consommé, served in a glass with freshly ground pepper and a slice of lemon.

2) Alcohol-free lager mixed with orange juice and lemon juice, decorated with slices of orange.

3) Angostura Bitters in a big glass filled up with tonic water and a slice of lime on top.

4) Tomato juice with a little Tabasco, served with a topping of finely chopped red peppers.

5) Strawberries and melon blended together and served in a small glass with fresh mint.

RELAX … LET THEM6) Iced coffee in a big glass mug served with a big scoop of ice cream on top.

LOOK AFTER YOU

Why must the show go on?

There really is no good reason. If you’re ill, recovering from an illness or operation, or just not able to cope for a bit, this is the time to call in the troops.

We must all try to break the habit of a lifetime, thinking we can deal with everything, and instead decide we should allow those who are concerned about us to do something to help. People actually

like

to be told what they can do if they offer to help. They are always offering, begging you to think of something they could do for you at this time. Suppose you were to say to people that there really were a few jobs which would be a huge help? Aren’t you truly delighted to do something to help someone else?

In fact, if we’re brutally honest, we would all prefer to do one fairly specific thing to help, rather than to sign on for life as a slave. So a truly thoughtful patient might just think up a list of ten little jobs for the ten people who had offered to help. They would then be overjoyed, and feel important and indispensable. You’d be doing them a favour. You could ask someone to:

Cut the grass.

Do the ironing.

Take out the rubbish bins.

Make you a soup.

Take the hound for a walk.

Vacuum the floor.

Defrost the fridge.

Paint your nails.

Go to the bookies.

And a million other things you can think of while you rest and recover your strength.

ANNOY THE PATIENT IN THE

NEXT BED

1) ‘Oh, was that your husband? I thought it was your son.’

2) ‘Very wise of you not to have too many visitors.’

3) ‘Will they be bringing you in a proper dressing gown at all?’

4) ‘Would you like this book someone gave me? It’s pure rubbish. I can’t bear it myself.’

HOSPITAL HORROR STORIES5) ‘You were talking in your sleep last night; I hope you don’t talk like that when you’re at home with your wife!’

There’s some awful, deep-seated thing in people that makes them tell you hospital horror stories when you’re not well.

There’s a kind of one-to-ten horror scale about these stories:

1) The hospital that was so high-tech no one understood anything.

2) The hospital that was falling down with old age.

3) The woman who was asked her age in front of everyone by a young pup in a white coat.

4) The nurse who behaved like a weasel because her romance was over.

5) The man who left his false teeth beside the bed and they were tidied away permanently.

6) The radiography department where they lose all the X-rays.

7) The time it took an hour for someone hacking about to find a vein to draw blood.

8) The hospital where they amputated the wrong leg.

9) The person who went in with one thing and came out with something much, much worse.

10) Something that was mis-diagnosed as trivial turned out to be fatal.

All of this is total nonsense. And worse, it is inappropriate nonsense. If you were prepared to listen you would hear equally insane horror stories from people about banks, garages, universities, cafés, airports and supermarkets. But you don’t feel so vulnerable in these places. You’re inclined to believe the gloom merchants when they talk about the horrors connected with illness. Why should you? The hospital has worked fine until now, why should it fall apart the day that you come in?

You will meet fine good people in hospital. Trust me. They’re well trained; they don’t flap in an emergency; they don’t faint when they see blood; they are mainly in this business because they do actually

care

about other people, and there is one sure thing about the nurses … they certainly are not in it for the money.

It is, in fact, very reassuring to be among professionals who know what is serious and who realise what definitely is only our own imagination working overtime. They speak soothingly. If you tell them you’re frightened and anxious, they won’t tell you to pull yourself together and develop a stronger backbone.