Ace of Spies (6 page)

Sigmund Rosenblum gave the name of solicitor L.J. Sandford to vouch for his application to be allowed to research into medieval art at the British Museum.

The secret of Melville’s success was undoubtedly his intelligence network. He was a meticulous man whose records suggest that he carefully checked out the backgrounds of his key informants. It is thanks to his intimate knowledge of those who were part of his network that we come closest to finally establishing solid documentary evidence concerning Reilly’s place and date of birth. Prior to his election as a Fellow of the Chemical Society, on 18 June 1896, Rosenblum had been required to submit official Russian documentation to establish his date and place of birth. While still in the possession of the society, pending the committee’s decision on membership, the document was perused by one of Melville’s officers, who, satisfied by the document’s authenticity, recorded in his report that Rosenblum was born on ‘11 March 1873 in Kherson, Russia’.

63

At this time Russia was still using the Julian calendar, which was thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar in use elsewhere. The date on the Russian document would therefore equate to 24 March in terms of the Gregorian calendar.

Agents and informers were the most significant intelligence sources Special Branch had in terms of the Russian and Polish

émigré communities, and were recruited in a variety of ways. Some were approached by detectives either on recommendation or through the course of everyday enquiries. A minority offered their services to officers. Whether they were approached or had volunteered, the motive was usually the same – money. Each officer had his own private circle of informers, whom he paid out of his own pocket and then claimed from his expenses. Sigmund Rosenblum, although well endowed with money when he arrived in England, had a propensity to spend his ill-gotten gains almost as quickly as he had come by them. Money was, as so often in his life, his prime motivator and the reason he became a Special Branch informer.

William Melville, the redoubtable Head of Scotland Yard’s Special Branch, who created ‘Sidney Reilly’.

To Melville, this émigré intelligence network was money well spent. As the chief commissioner of the Metropolitan Police made clear in a memorandum to the under secretary of the Home Department, this area of intelligence gathering was one that was very difficult for officers to participate in directly due to the language and cultural barriers of the community they were seeking to infiltrate.

64

Rosenblum was particularly useful in that he had a network of his own contacts that transcended the narrow

world of émigré politics. By courting journalists, professional contacts and those he encountered in the gambling clubs and other less than salubrious establishments he frequented, he had a unique pool of sources. He kept his ear to the ground and reported back to Melville on anything that struck him as being of interest.

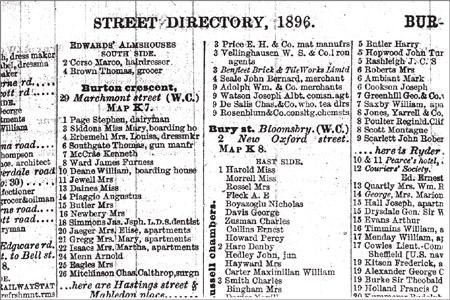

Rosenblum & Company was to all intents and purposes a patent medicine racket set up in 1896.

Apart from selling information, Rosenblum was also developing his legitimate business interests. In 1897 he moved Rosenblum & Co. from Bury Court to Imperial Chambers at 3 Cursitor Street, Holborn, where he also took up residence. Unlike South Lambeth Road, Cursitor Street was at the hub of London life, adjacent to the law courts, Fleet Street and the City. Rosenblum, who later in life would be dubbed ‘The Man Who Knew Everything’,

65

was in his element at Cursitor Street, where several well-connected Fleet Street journalists also lived.

66

It is not hard to imagine the gregarious and avuncular Rosenblum keeping the drinks flowing for his journalist friends in the Imperial Club on the ground floor of 3 Cursitor Street, listening avidly to their gossip and inside stories.

At the same time as he moved his business to Cursitor Street, he also changed its name to the ‘Ozone Preparations Company’. Unlike most consultant chemists, Rosenblum’s business activity lay more in the field of patent medicine peddling than in the more professional field of consultancy work. The patent medicine racket was almost totally dependent upon advertising miracle cures to the gullible. The Institute of Chemistry had, since 1893, taken a strong line against its members advertising – a contentious issue among its membership, a number of whom dissented from this ruling.

67

Not wishing to court expulsion from such a prestigious body and thus losing his FIC suffix, Rosenblum concocted a scheme which would enable him to continue advertising unhindered, while at the same time retaining his membership of the institute. By changing the name of the business from his own to that of a corporate trading identity, he concealed his connection with the business. He also covered the tracks of Rosenblum & Co. by moving the business to new premises. Although the accommodation at Cursitor Street was somewhat restricting, space was not a major consideration as he was not actually manufacturing the products himself, but buying from drug manufacturers and selling on the repackaged potions to customers.

While the patent medicine business was booming, both in Britain and in the United States, it was certainly not making the kind of money necessary for Rosenblum to finance the lifestyle to which he had become accustomed. The fact that he moved from the wellappointed and spacious apartment in Albert Mansions to a smaller one in Cursitor Street, from where he also ran his business, suggests that by 1897 the money he had initially brought with him from France was running low, and he was looking to make econo-mies. It was in the summer of that year that he first met Margaret Thomas. As we have already seen, she was a temptation he could not resist in more ways than one, but was she all she seemed to be?

To all intents and purposes, anyone meeting Margaret Thomas for the first time in the late 1890s would, no doubt, have taken her at face value, as an educated and cultured Englishwoman of

the Victorian upper classes. The reality, however, was anything but. Margaret Callaghan was born in the southern Irish fishing village of Courtown Harbour, County Wexford, on 1 January 1874,

68

the eldest daughter of Edward and Anne Callaghan.

69

She and her brothers and sisters grew up in a small cottage very close to that of her cousins Patrick, James and Elizabeth. She left Courtown Harbour in 1889 to join her elder brother, James,

70

who had headed for England in search of better prospects, and was now living in Didsbury, Manchester. She found a position in the household of Edward Birley, in nearby Altrincham, and three years later moved to London to work for Birley’s cousin, the Reverend Hugh Thomas. This much is on the official record. It is once she arrives in London, however, that the manipulation and fabrication of her life begins in earnest, instigated primarily by herself.

When she married Hugh Thomas in 1895, for example, she wrote in the marriage register that her father’s name was Edward Callaghan, a seaman.

71

Whilst not being an outright lie, it was certainly a profound exaggeration. Edward Callaghan was a smalltime fisherman who, like generations of his family before him, had worked the fishing grounds off the coast of Wexford, with his brothers John and David. Less than three years later her story had been refined and further embellished. When she married Sigmund Rosenblum in August 1898, she stated on the marriage register that her father was deceased, and that his name was Edward Reilly Callaghan, a captain in the navy.

72

Apart from the fact that Edward Callaghan was still very much alive in 1898, his fictional promotion from naval rating to an officer and captain was certainly more in keeping with her social pretensions.

According to the marriage register, the two witnesses at the ceremony were Charles Cross and Joseph Bell. Bell at this time was a clerk at the Admiralty, while Charles Cross was a local government official. Whether they were acquaintances of the bride or groom is not immediately apparent. However, it is noteworthy that both eventually married daughters of Henry Freeman Pannett, a one-time associate of William Melville.

73

It has been claimed that Sigmund Rosenblum adopted the name Reilly from his father-in-law’s middle name.

74

If this was indeed the case, why had Margaret not declared this middle name on her 1895 marriage certificate? If Reilly was her father’s middle name, then it would have been given to him at baptism. His baptismal records show, however, that this was not the case.

75

Why then did Margaret introduce the name Reilly into the official record when she married Sigmund Rosenblum?

The answer lies in the fact that Rosenblum wanted a new, legitimate identity, not merely the assumption of a

nom de plume

as he had used on many occasions in the past. If he was to return to Russia in the future, his new identity would need to be a watertight one that would be able to stand up to official scrutiny. This would best be achieved by acquiring a British passport. Obtaining a passport through official channels would have been no simple matter for Rosenblum. The easiest way, theoretically, would have been to apply for naturalisation on the grounds that he had married a British subject. Having been resident in England for less than three years at this point, he could not have applied for citizenship on residential grounds. If, having gained naturalisation, he then applied for a British passport, under the regulations it would have been issued with ‘Naturalised British Subject’ emblazoned on it.

76

This would have been useless to Rosenblum as it would indicate quite clearly to anyone examining it that he had previously been a citizen of another country and was not British by birth. Furthermore, by adopting this approach, the passport would have been issued under the name Rosenblum, which again would have defeated the whole object of seeking a new identity. Rosenblum therefore needed a British passport in a new name, indicating the holder to have been born in Britain. Obtaining such a passport was motivated purely by the need to provide a new identity in Russia or in Russian-held territory. Although returning to Russia had been on his mind for some while, he certainly had every intention of retaining his British connections and wished, in due course,

to adopt the Reilly identity legi-timately under English law by Deed Poll. This was why Margaret included the name Reilly on their marriage record. Should the question ever be raised in the future as to why they wished to adopt the name Reilly, they could fall back on the claim that it was her father’s name and produce the marriage certificate. It was not unusual for Jews either to anglicise their surnames or to change them completely. The story that it came from his father-in-law was therefore a justification or validation for using the name Reilly, not the origin of it.