Ace of Spies (5 page)

A dramatic event occurred on a train between Paris and Fontainebleau… on opening the door of one of the coaches, the railway staff discovered an unfortunate passenger lying unconscious in the middle of a pool of blood. His throat had been cut and his body bore the marks of numerous knife wounds. Terrified at the sight, the station staff hastened to inform

the special investigator who started preliminary enquiries and sent the wounded man to the hospital in Fontainebleau.

The report went on to relate how, on the afternoon following the attack, 26 December, the man had briefly regained consciousness and been questioned by the public prosecutor’s department. Apart from revealing that he was a thirty-seven-year-old Italian citizen by the name of Constant Della Cassa, he was unable or unwilling to give them anything more than an elementary account of what had happened to him. According to Della Cassa he had been attacked at Saint-Maur by two men. He refused to say how much cash had been stolen or whether he was alone in the compartment at the time of the attack. The public prosecutor’s office were certainly of the view that it had been a sizeable sum due to the fact that 362 francs had been left behind by the attackers. A ticket found in his jacket pocket indicated that he had boarded the train at Maisons-Alfort. Although Della Cassa gave no description of his attackers, the two men had been seen alighting the train at the station after Saint-Maur.

The following day, 28 December, Le Centre reported that Della Casa, of 3 rue de Normandie, Paris, had died from his wounds in Fontainebleau Hospital. The report also stated that he had been identified by police as an anarchist. Although an enquiry was immediately set up by the French authorities, it failed to shed any further light on the robbery or lead to any arrests in connection with the crime. By the time Le Centre announced Della Cassa’s death, at least one of the culprits was already on his way to England. London was an obvious destination, where émigrés from Europe were welcomed as refugees, in keeping with Britain’s tradition of providing sanctuary for victims of political persecution.

Rosenblum’s most likely route from Paris would have been the boat train service from the Gare du Nord to London, via Dieppe and Newhaven. According to the 1895 timetable, the ferry

Tamise

departed from Dieppe at 1.15p.m., bound for Newhaven. The London & Paris Hotel would therefore have been among his first

sights of England. It would be another decade before any meaningful controls were placed on entry to the UK by foreign nationals, and he would therefore have passed unhindered through the quay-side customs point and proceeded by rail to London.

Being well supplied with money and being a creature of habit, Rosenblum would more than likely have spent a short period in a comfortable hotel before finding a more permanent residence. We know from local government records that he moved into Albert Mansions, a newly completed prestigious apartment block in Rosetta Street, Lambeth, in early 1896.

47

He was also able to acquire business premises, albeit just two rooms, at 9 Bury Court, in the City of London, from where he established ‘Rosenblum & Company’.

48

Ostensibly a consultant chemist, Rosenblum was, to all intents and purposes, a patent medicine salesman who went to extraordinary lengths to acquire

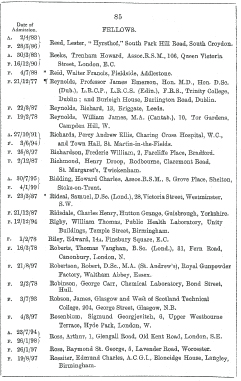

a cloak of professional respectability for himself. Within six months he had succeeded in being admitted to the Chemical Society as a Fellow,

49

although it would take a further nine months to gain a fellowship of the more prestigious Institute of Chemistry.

50

Sigmund Rosenblum’s entry in the Institute of Chemistry’s Register of Fellows, where he elevated his Paddington address to ‘Hyde Park’.

In order to have gained a fellowship, he would not only have to have demonstrated degree level knowledge of chemistry,

51

but would also have needed the support and sponsorship of other Fellows. Circumstantial evidence indicates that Reilly set about gaining this. We know, for example, that his neighbour at Albert Mansions, William Fox,

52

had been a Fellow of the Institute of Chemistry since 1889, and that another Fellow, Boverton Redwood, was a member of the Russian Technical Society, of which Rosenblum was also a member. A further Russian connection with the Institute of Chemistry, albeit an indirect one, was another institute member, Lucy Boole, the sister of the novelist Ethel Voynich (

née

Boole).

According to Robin Bruce Lockhart, Ethel met Sigmund Rosenblum in London in 1895 and became his mistress.

53

He further asserts that they went to Italy together with the last £300 he had. During this sojourn Rosenblum apparently ‘bared his soul to his mistress’, and revealed to her the story of his mysterious past. After their brief affair had ended, she published in 1897 a critically acclaimed novel,

The Gadfly,

the central character of which, Arthur Burton, was, according to Rosenblum, largely based on his own early life.

54

In reality, this is but one more example of Rosenblum’s ability to turn reality on its head. The truth about this remarkable book, and how its equally remarkable author came to write it, can be found in Appendix 1.

EthelVoynich was a significant figure not only on the late Victorian literary scene but also in Russian émigré circles. It is surprising that her political role has received only minimal attention from those writing about Sidney Reilly, for it is through her connections that important clues concerning Reilly and his activities in England are to be found. It was at her mother’s house at 16 Ladbroke

Grove, Notting Hill, that Ethel first met Sergei Kravchinsky, a lynchpin in London’s Russian émigré community. Kravchinsky, or Stepniak as he now called himself, had fled from St Petersburg in 1878, where, in broad daylight, he had stabbed to death Gen. Mezentsev, the head of the Ochrana. Ethel offered to support Stepniak in his revolutionary work, and immediately began helping him in organising the ‘Society of Friends of Russian Freedom’. She soon became a member of the society’s council and worked on the editorial of their monthly publication,

Free Russia.

Through Stepniak she became acquainted with other revolutionaries such as Eleanor Marx, Friedrich Engels, Georgi Plekhanov, and the man she would eventually marry, Wilfred Voynich.

In 1895 Stepniak died in a rail accident and Wilfred Voynich, among others, began to play a more central role in the society’s covert activities. Ostensibly a London bookshop owner, Voynich became instrumental in smuggling the society’s texts and propaganda into Russia through a network of couriers under the cover of his book business. The Ochrana had good reason to believe that his business dealings were also a front for the raising and laundering of revolutionary funds. There seems little doubt that the British authorities as well knew a great deal about Voynich and his activities. Clearly someone close to Wilfred was supplying inside information, but who? What grounds are there for suspecting that it might have been Rosenblum? He certainly had a great deal in common with Wilfred, being a fellow chemist with a keen interest in medieval art and antiquarian books. This would almost certainly have helped him to win Wilfred’s acceptance and confidence. Wilfred was also born in the same district of Kovno in Lithuania as Rosenblum’s cousin Lev Bramson.

55

Being of a similar age and sharing radical political views, Wilfred and Bramson no doubt moved in the same circles and knew each other long before Wilfred and Sigmund Rosenblum came to reside in London.

The fact that they were indeed friends and associates is confirmed by an Ochrana report concerning members of the society of

Friends of Russian Freedom which states that Rosenblum was, ‘a close friend of Voynich’s and especially his wife’s. He accompanies her everywhere, even on her trips to the con-tinent’.

56

Whether this statement should be interpreted as implying or confirming any romantic attachment between Sigmund and Ethel is a highly debatable point. It is clear from Ethel’s own statements about this period that she was an active courier for the ‘Free Russia’ cause and travelled abroad frequently. Wilfred may well have felt that Ethel needed a protective companion to accomp-any her, knowing full well that the Ochrana would no doubt be keeping an eye on her movements. Who better than his trusted friend Sigmund? Besides which, anecdotal family sources indicate that Ethel’s sexual preferences may well have precluded a romantic attachment to Rosenblum, or indeed any other man, come to that.

57

According to the same Ochrana report, other active émigré members of the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom included:

Aladyin, A.F. (43 Sulgrave Road, Hammersmith): moved to London from Paris, first attended all gatherings of Russian and Polish revolutionaries, but now, in view of suspicion of espionage, has broken all such ties and meets only with Goldenberg.

Goldenberg, Leon (15 Augustus Road, Hammersmith): since his arrival from New York in 1895 he has been the manager of the office of the ‘Society of Friends for Russian Freedom’. He maintains relations with almost all Russian and Polish revolutionaries.

Volkhovsky, Felix (47 Tunley Road, Tooting): an active revolutionary, often gives lectures on his exile to Siberia. Took over from Kravchinsky after his death.

Chaikovsky, Nikolai (1 College Terrace, Harrow): a famous emigrant, the Poles believe him to be an agent of the Russian government. He has recently been seen meeting the Greek Mitzakis, who frequently travels to St Petersburg.

Rothstein, Fedor (65 Sidney Street, Mile End): made a speech at the last socialist congress in London under the name of Duchowietzky. A very active revolutionary, moves in Russian and Polish revolutionary circles. Took an active part in the last revolutionary rally on Trafalgar Square, standing next to other speakers by the pedestal of Nelson’s Column.

Voynich, Wilfred, alias Kelchevsky (Great Russell Mansions, Great Russell Street, Office Soho Square): took an active part in the revolutionary movement, but now is more inclined to literary work, also on revolutionary issues. Holds an annual international revolutionary library. His wife is British, a novelist.

Wilfred Voynich’s remarkable and consistent success in acquiring rare medieval manuscripts prompted a number of theories regarding the sudden appearance of these previously unknown items. According to one theory, he was acquiring supplies of unused medieval paper from Europe and using his knowledge as a chemist to replicate medieval inks and paints, thus enabling him to create ‘new’ medieval manuscripts to order. One of Voynich’s early employees, Millicent Sowerby, confirms that he sold blank fifteenth-century paper to select customers for a shilling a sheet.

58

While this confirms that he at least had access to the paper, what evidence is there to suggest that either he or Rosenblum had the capability to recreate medieval paints and inks? The best source for anyone wanting to research the composition of such properties was the British Museum Library, whose extensive collection contained numerous volumes on medieval art and manuscripts.

Perusal of the museum’s records reveals that on 17 December 1898 the principal librarian received a letter of application from one Sigmund Rosenblum seeking a reader’s ticket to enable him to use the Reading Room. According to his letter of application he was a ‘chemist and physicist’ wishing to study medieval art; a character reference provided by Leslie Sandford of the legal firm Willett and Sandford intriguingly states that Rosenblum

was ‘engaged in scientific research of great importance to the community’.

59

A reader’s ticket was issued and Rosenblum began his research on 2 January 1899. Of course, he could have had other or indeed additional motives for his research, which are explored later in this chapter.

If Rosenblum was informing on Voynich, to whom was he supplying the information? Prior to the creation of the Secret Service Bureau in 1909 (the forerunner of MI5 and MI6), émigré matters were the preserve of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch. ‘The Branch’ had been created in 1887 as a successor to the Special Irish Branch. Unlike the SIB, however, the new Special Branch had a much wider ‘anti-subversion’ remit than purely countering Irish Republican terrorism. Under its first chief, Scotsman John Littlechild, the Branch consisted of no more than thirty officers. Littlechild resigned in April 1893, to establish his own private detective agency, and was succeeded by William Melville, under whose leadership the Branch grew in size and reputation, establishing itself as a power in the world of secret agencies.

60

Born a Roman Catholic in Sneem, County Kerry, on 25 April 1850, William Melville joined the Metropolitan Police on 16 September 1872, and was a member of the SIB from its inception in 1883.

61

He was, without doubt, one of the most intriguing and distinguished men ever to lead the Special Branch, holding the post for ten years before mysteriously resigning at the peak of his police career in 1903. Prior to his appointment he had been in Section B, in charge of ‘counter-refugee operations’, a responsibility that gave him an intimate knowledge of political exiles, émigré groups and ‘undesirables’ of all varieties. He was described by colleagues as a ‘big broad-shouldered man with tremendous strength and unlimited courage’.

62

From contemporary police reports and newspaper coverage, Melville comes across as an effective and single-minded officer who was the antithesis of almost everything the Scotland Yard detective chief inspector was portrayed to be by the popular media of the time.