A Writer's Diary (30 page)

Authors: Virginia Woolf

But then, next day, today, which is Thursday, one week later, the other thing begins to workâthe exalted sense of being above time and death which comes from being again in a writing mood. And this is not an illusion, so far as I can tell. Certainly I have a strong sense that Roger would be all on one's side in this excitement, and that whatever the invisible force does, we thus get outside it. A nice letter from Helen. And today we go to Worthingâ

Sunday, September 30th

The last words of the nameless book were written 10 minutes ago, quite calmly too. 900 pages: L. says 200,000 words. Lord God what an amount of re-writing that means! But also, how heavenly to have brought the pen to a stop at the last line, even if most of the lines have now to be rubbed out. Anyhow the design is there. And it has taken a little less than 2 years: some months less indeed, as

Flush

intervened; therefore it has been written at a greater gallop than any of my books. The representational part accounts for the fluency. And I should sayâbut do I always say this?âwith greater excitement: not, I think, of the same kind quite. For I have been more general, less personal. No "beautiful writing"; much easier dialogue; but a great strain, because so many more faculties had to keep going at once, though none so pressed upon. No tears and exaltation at the end; but peace and breadth, I hope. Anyhow, if I die tomorrow, the line is there. And I am fresh; and shall re-write the end tomorrow. I don't think I'm fresh enough, though, to go on "making up." That was the strainâthe invention: and I suspect that the last 20 pages have slightly flagged. Too many odds and ends to sweep up. But I have no idea of the wholeâ

Tuesday, October 2nd

Yes, but my head will never let me glory sweepingly; always a tumble. Yesterday morning the old rays of light set in; and then the sharp, the very sharp pain over my eyes; so that I sat and lay about till tea; had no walk, had not a single idea of triumph or relief. L. bought me a little travelling ink pot, by way of congratulation. I wish I could think of a name.

Sons and Daughters?

Probably used already. There's a mass to be done to the last chapter, which I shall, I hope, d.v., as they say in some circles, I suppose, still, begin tomorrow; while the putty is still soft.

So the summer is ended. Until 9th of September, when Nessa came across the terraceâhow I hear that cry He's deadâa very vigorous, happy summer. Oh the joy of walking! I've never felt it so strong in me. Cowper Powys, oddly enough, expresses the same thing: the trance like, swimming, flying

through the air; the current of sensations and ideas; and the slow, but fresh change of down, of road, of colour; all this churned up into a fine thin sheet of perfect calm happiness. It's true I often painted the brightest pictures on the sheet and often talked aloud. Lord how many pages of

Sons and Daughters

âperhaps

Daughters and Sons

would give a rhythm more unlike

Sons and Lovers,

or

Wives and Daughtersâ1

made up, chattering them in my excitement on the top of the down, in the folds. Too many buildings, alas; and gossip to the effect that Christie and the Ringmer Building Co. are buying Botten's Farm to build on. Sunday I was worried, walking to Lewes, by the cars and the villas. But again, I've discovered the ghostly farm walk; and the Piddinghoe walk; and such variety and lovelinessâthe river lead and silver; the shipâServic of Londonâgoing down: the bridge opened. Mushrooms and the garden at night: the moon, like a dying dolphin's eye; or red orange, the harvest moon; or polished like a steel knife; or lambent; sometimes rushing across the sky; sometimes hanging among the branches. Now in October the thick wet mist has come, thickening and blotting. On Sunday we had Bunny and Julian.

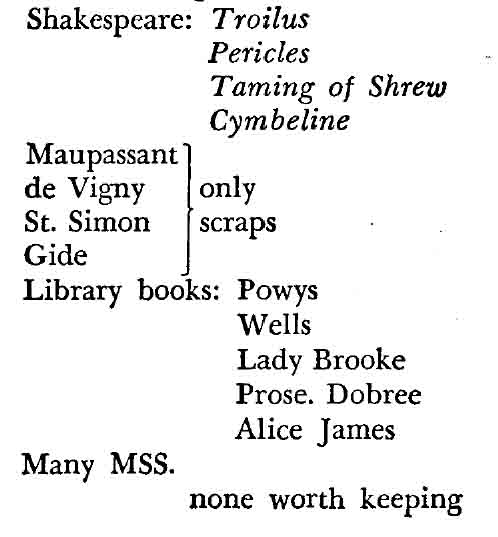

Books read or in reading.

Thursday, October 4th

A violent rain storm on the pond. The pond is covered with little white thorns; springing up and down: the pond is bristling with leaping white thorns, like the thorns on a small porcupine; bristles; then black waves; cross it; black shudders; and the little water thorns are white; a helter skelter rain and the elms tossing it up and down; the pond overflowing on one side; lily leaves tugging; the red flower swimming about; one leaf flapping; then completely smooth for a moment; then prickled; thorns like glass; but leaping up and down incessantly; a rapid smirch of shadow. Now light from the sun; green and red; shiny; the pond a sage green; the grass brilliant green; red berries on the hedges; the cows very white; purple over Asheham.

Thursday, October 11th

A brief note. In today's

Lit. Sup.,

they advertise

Men Without Art,

by Wyndham Lewis: chapters on Eliot, Faulkner, Hemingway, Virginia Woolf ... Now I know by reason and instinct that this is an attack; that I am publicly demolished; nothing is left of me in Oxford and Cambridge and places where the young read Wyndham Lewis. My instinct is not to read it. And for that reason: Well, I open Keats and find: "Praise or blame has but a momentary effect on the man whose love of beauty in the abstract makes him a severe critic on his own works. My own domestic criticism has given me pain beyond what Blackwood or Quarterly could possibly inflict ... This is a mere matter of the momentâI think I shall be among the English poets after my death. Even as a matter of present interest the attempt to crush me in the Quarterly has only brought me more into notice."

Well: do I think I shall be among the English novelists after my death? I hardly ever think about it. Why then do I shrink from reading W. L.? Why am I sensitive? I think vanity: I dislike the thought of being laughed at: of the glow of satisfaction that A., B. and C. will get from hearing V. W. demolished: also it will strengthen further attacks: perhaps I feel uncertain of my own gifts: but then, I know more about

them than W L.: and anyhow I intend to go on writing. What I shall do is craftily to gather the nature of the indictment from talk and reviews; and, in a year perhaps, when my book is out, I shall read it. Already I am feeling the calm that always comes to me with abuse: my back is against the wall: I am writing for the sake of writing, etc.; and then there is the queer disreputable pleasure in being abusedâin being a figure, in being a martyr, and so on.

Sunday, October 14th

The trouble is I have used every ounce of my creative writing mind in

The Pargiters.

No headache (save what Elly calls typical migraineâshe came to see L. about his strain yesterday). I cannot put spurs in my flanks. It's true I've planned the romantic chapter of notes: but I can't set to. This morning I've taken the arrow of W. L. to my heart: he makes tremendous and delightful fun of B. and B.:

*

calls me a peeper, not a looker; a fundamental prude; but one of the four or five living (so it seems) who is an artist. That's what I gather the flagellation amounts to: (Oh I'm underrated, Edith Sitwell says). Well: this gnat has settled and stung: and I think (12:30) the pain is over. Yes. I think it's now rippling away. Only I can't write. When will my brain revive? In 10 days I think. And it can read admirably: I began

The Seasons

last night ... Well: I was going to say, I'm glad that I need not and cannot write, because the danger of being attacked is that it makes one answer backâa perfectly fatal thing to do. I mean, fatal to arrange

The P.s

so as to meet his criticisms. And I think my revelation two years ago stands me in sublime stead: to adventure and discover and allow no rigid poses: to be supple and naked to the truth. If there is truth in W. L., well, face it: I've no doubt I'm prudish and peeping. Well then live more boldly, but for God's sake don't try to bend my writing one way or the other. Not that one can. And there is the odd pleasure too of being abused and the feeling of being dismissed into obscurity is also pleasant and salutary.

Tuesday, October 16th

Quite cured today. So the W. L. illness lasted two days. Helped off by old Ethel's bluff affection and stir yesterday by buying a blouse; by falling fast asleep after dinner.

Writing away this morning.

I am so sleepy. Is this age? I can't shake it off. And so gloomy. That's the end of the book. I looked up past diariesâa reason for keeping them, and found the same misery after

Wavesâ

after

Lighthouse.

I was, I remember, nearer suicide, seriously, than since 1913. It is after all natural. I've been galloping now for three monthsâso excited I made a plunge at my paperâwell, cut that all offâafter the first divine relief, of course some terrible blankness must spread. There's nothing left of the people, of the ideas, of the strain, of the whole life in short that has been racing round my brain: not only the brain; it has seized hold of my leisure; think how I used to sit still on the same railway linesârunning on my book. Well, so there's nothing to be done the next two or three or even four weeks but dandle oneself; refuse to face it; refuse to think about it. This time Roger makes it harder than usual. We had tea with Nessa yesterday. Yes, his death is worse than Lytton's. Why, I wonder? Such a blank wall. Such a silence: such a poverty. How he reverberated!

Monday, October 29th

Reading

Antigone.

How powerful that spell is stillâGreek, an emotion different from any other. I will read Plotinus: Herodotus: Homer I think.

Thursday, November 1st

Ideas that came to me last night dining with Clive; talking to Aldous

*

and the Kenneth Clarks.

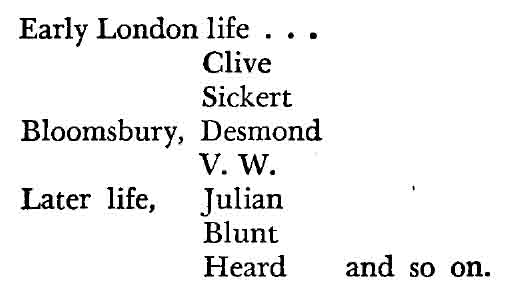

About Roger's life: that it should be written by different people to illustrate different stages.

Youth, by Margery

â

Cambridge, by Wedd?

all to be combined say by Desmond and me together. About novels: the different strata of being: the upper, under. This is a familiar idea, partly tried in the Pargiters. But I think of writing it out more closely; and now, particularly, in my critical book: showing how the mind naturally follows that order in thinking: how it is illustrated by literature.

I must now do biography and autobiography.

Friday, November 2nd

Two teeth out with a new anaesthetic: hence I write here, not seriously. And this is another pen. And my brain is very slightly frozen, like my gums. Teeth become like old roots that one breaks off. He broke and I scarcely felt. My brain frozen thinks of Aldous and the Clarks: thinks vaguely of biography; thinks am I reviewed anywhereâcan't lookâthinks it is a fine cold day.

I went upstairs to rinse my bleeding gumâthe cocaine lasts ½ an hour; then the nerves begin to feel againâand opened the

Spectator

and read W. L. on me again. An answer to Spender. "I am not malicious. Several people call Mrs. W. Felicia Hemans." This I suppose is another little scratch of the cat's claws: to slip that in, by the wayâ"I don't say itâothers do." And so they are supercilious on the next page about Sickert; and soâWell L. says I should be contemptible to mind. Yes: but I do mind for 10 minutes: I mind being in the light again, just as I was sinking into my populous obscurity. I must take a pull on myself. I don't think this attack will last more than two days. I think I shall be free from the infection by Monday. But what a bore it all is. And how many sudden

shoots into nothingness open before me. But wait one moment. At the worst, should I be a quite negligible writer, I enjoy writing: I think I am an honest observer. Therefore the world will go on providing me with excitement whether I can use it or not. Also, how am I to balance W. L.'s criticism with Yeatsâlet alone Goldie and Morgan? Would they have felt anything if I had been negligible? And about two in the morning I am possessed of a remarkable sense of (driving eyeless) strength. And I have L. and there are his books; and our life together. And freedom, now, from money paring. And ... if only for a time I could completely forget myself, my reviews, my fame, my sink in the scaleâwhich is bound to come now and to last about 8 or 9 yearsâthen I should be what I mostly am: very rapid, excited, amused, intense. Odd, these extravagant ups and downs of reputation; compare the Americans in the

Mercury

... No, for God's sake don't compare: let all praise and blame sink to the bottom or float to the top and let me go my ways indifferent. And care for people. And let fly, in life, on all sides.