A History of Zionism (103 page)

Read A History of Zionism Online

Authors: Walter Laqueur

Tags: #History, #Israel, #Jewish Studies, #Social History, #20th Century, #Sociology & Anthropology: Professional, #c 1700 to c 1800, #Middle East, #Nationalism, #Sociology, #Jewish, #Palestine, #History of specific racial & ethnic groups, #Political Science, #Social Science, #c 1800 to c 1900, #Zionism, #Political Ideologies, #Social & cultural history

The psychological background to this mood was the profound horror caused by the murder of millions of Jews in Europe, and the absence of any effective reaction on the part of the civilised world. The liberal element in Zionism, the faith in humanity, suffered a blow from which it was not fully to recover. The appeals to fraternal help, to human solidarity, to which a former generation of Zionists was accustomed, no longer found a ready response. In the hour of their deepest peril few had stood by them, there had been pious platitudes and much hand-wringing but little real help. They had learned their lesson: no one could be trusted, it was everyone for himself.

The story of the holocaust has been told in great and dreadful detail. The first reliable reports of the mass murder were received in late 1942 from the representatives of the Jewish Agency in Switzerland. The State Department reacted by banning the transmission of such news through diplomatic channels from Switzerland. A conference in Bermuda in early 1943 called to deal with the refugee problem was a total failure. Even in July 1944, when the tide of war had finally turned and there seemed to be a real chance to save many thousands of Hungarian Jews, there was no willingness in the west to come to their help. Himmler and Eichmann had suggested that the dispatch of Jews to Auschwitz would be stopped in exchange for ten thousand trucks. But when Weizmann and Shertok saw Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, they were told that there must be no negotiation with the enemy. All they got from Churchill was a promise that those involved in the mass murder would be put to death after the war.

The Jewish Agency asked that the death camps at Auschwitz should be bombed if only, as Weizmann said, ‘to give the lie to the oft-repeated assertions of Nazi spokesmen that the Allies are not really so displeased with the action of the Nazis in ridding Europe of the Jews’.

*

But the answer was again that this was impossible. On 1 September 1944 Weizmann was told by Eden that the Royal Air Force had rejected the request for technical reasons. Similar attempts by Dr Goldmann in Washington, and by American officials such as John Pehle of the War Refugee Board, were equally unsuccessful. The answer of John McCloy, assistant secretary of the army, deserves to be quoted:

After a study it became apparent that such an operation could be executed only by diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere and would in any case be of such doubtful efficacy that it would not warrant the use of our resources. There has been considerable opinion to the effect that such an effort, even if practicable, might provoke more vindictive action by the Germans.

It remained the secret of the War Department what more vindictive action than Auschwitz could have been expected.

*

What shocked the Jews so much was not that the rescue operations were ineffective. It might have been possible to save more Hungarian Jews and to delay the process of extermination by direct air attacks. The oilfields of Ploesti in Rumania, equally distant from London, had been bombed despite technical difficulties. Whether these measures would have served their purpose is not at all certain. Once Hitler had set his mind on exterminating European Jewry, once the Nazi machinery was set in motion, rescue efforts could not radically affect the situation. The only effective way to rescue Jews was to defeat Nazism as quickly as possible. But for the allied victory Palestinian Jewry too would have been doomed. Zionism had no panacea for a threat of this magnitude. All this is true, but it does not explain, let alone justify, the absence of any serious attempt to help the Jews in their hour of mortal danger. There was a wall of indifference which shut off even the narrowest path of escape. The feeling among the survivors was that in their own country, in the case of a Nazi victory, they would have gone down fighting, not been led to the slaughter like cattle. It was this widespread mood which gave Zionism a tremendous impetus at the end of the war.

The extent of the Jewish catastrophe became fully known during 1944. But it was only in the last months of the war, when the first extermination camps fell into allied hands, that the full significance of the disaster was realised. Up to that time there had been a lingering belief that the news about genocide had perhaps been exaggerated, that more Jews had survived than originally assumed. By April 1945 there were no longer any doubts. Of more than three million Jews in Poland, fewer than a hundred thousand had survived; of 500,000 German Jews - 12,000. Czechoslovakia once had a Jewish community of more than 300,000, of whom about 40,000 were still alive. Of 130,000 Dutch Jews some 20,000 still existed, of 90,000 Belgian Jews - 25,000; of 75,000 Greek Jews - 10,000. The only countries where the losses were relatively lighter were Rumania (320,000) and Hungary (200,000), but there too the Jewish community had been more than twice those sizes before the war. It is estimated, though exact figures could not be obtained, that the Jewish population of the Soviet Union was halved as the result of Nazi mass killings. In a few countries, in Bulgaria, Italy and Denmark, the majority had survived, either because the local authorities had protected them or because of certain fortunate local circumstances. But these were countries with small Jewish communities; the big concentrations had disappeared. Roughly speaking, out of every seven Jews living in Europe, six had been killed during the war.

In the 1920s there had been widely read novels describing the exodus of Jews from Vienna and Berlin. The authors of these works of political science fiction had independently reached the conclusion that these two great capitals were not able to manage without the Jews and that eventually they had to implore them to return. The first part of the prediction had come true. In Vienna, once a community of 180,000, two hundred Jews had survived with the knowledge of the Nazis; eight hundred, as it later appeared, had been in hiding and lived to see the day of deliverance; 2,500 elderly people returned from the Terezin show camp. This was the total that remained of a community that had once helped to make Vienna one of the great capitals of the world. Hitler had lived in Vienna as a young man. It was there that he had become an antisemite, and the Viennese Jews were persecuted with special ferocity. Nor was it a matter of surprise that hardly a Jew survived in the capital of the Reich. But the Nazi bureaucratic machinery worked relentlessly everywhere: Hitler had never been to Greece and had no particular grudge against the Jews of Salonika. Nevertheless, of the 56,000 in that city, only 2,000 were alive when the war ended.

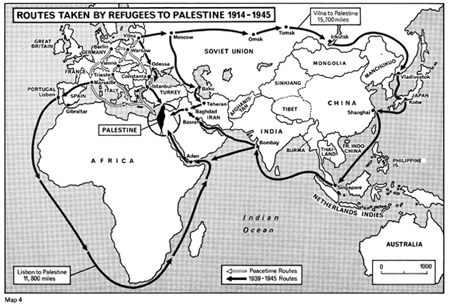

Of the remnant of European Jewry many were refugees from their native lands. Tens of thousands of Polish Jews had found temporary shelter in the Soviet Union but did not want to remain there, nor did they intend to settle in Poland. Switzerland had given refuge to 26,000, Sweden to 13,000, Belgium to 8,000. Britain had absorbed some 50,000 altogether and many had found shelter in France. The smaller European countries were eager to get rid of the aliens, but where were they to go? Few of them were ready to start life afresh in Germany, or indeed anywhere on a continent which had become the slaughterhouse of their families and their people.

As a result of the holocaust, the idea of the Jewish state seemed to have lost its historical

raison d’être.

Herzl and Nordau had thought of the Jewish state as a haven for the persecuted European Jews; Jabotinsky had written about the ‘objective’ Jewish question; the Biltmore programme had been based on the assumption that millions of Jews would survive the war. The prophets of Zionism had anticipated persecution and expulsion but not the solution of the Jewish question by mass murder. As the war ended Zionism seemed to be at the end of its tether.

There were victory celebrations on VE day in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa, as in most European cities. The shops had sold out all flags and no material for banners could be had. A flag with black borders was flown in Tel Aviv in memory of those who had been killed. Chief Rabbis Herzog and Uziel declared a day of thanksgiving, on which psalms 100 and 118 were to be read, as well as a special prayer - that wisdom, strength and courage might be given to the rulers of the world to restore the chosen people to their freedom, and peace in the Holy Land. A hundred thousand people converged on the streets of Tel Aviv and shouted ‘Open the gates of Palestine’. In the night of this rejoicing and thanksgiving Ben Gurion noted in his diary: ‘Rejoice not, o Israel, for joy, like other peoples’ (Hosea 9, 1).

*

The war in Europe was over, the world had been liberated from Nazi terror and oppression, peace had returned. For the Jewish people it was the peace of the graveyard. Yet paradoxically, at the very time when the ‘objective Jewish question’ had all but disappeared, the issue of a Jewish state became more topical than ever before. The countries around Palestine were all well advanced on the road to independence. The Jewish community in Palestine had come of age during the war; it was now to all intents and purposes a state within a state, with its own schools and public services, even an army of its own. The victors in the war had an uneasy conscience, as the stark tragedy of the Jewish people unfolded before their eyes. It was only now that the question was asked whether enough had been done to help them and what could be done for the survivors.

Before the war Zionism had been a minority movement - sometimes a small minority - in the Jewish community. But in 1945 even its former enemies rallied to the blue and white flag. Typical of this conversion was the May Day 1945 speech in Manchester, by the new chairman of the British Labour Party, Harold Laski. He felt like the prodigal son coming home, Professor Laski said; he did not believe in the Jewish religion and was still a Marxist; before the war he had been an advocate of assimilation and had thought that to lose their identity was the best service which the Jews could do for mankind. But now he was firmly and utterly convinced of the necessity of the rebirth of the Jewish nation in Palestine. They were all Zionists now.

*

M. Mischnitzer,

To Dwell in Safety

, Philadelphia, 1948, p. 196

et seq.

†

A.A. Aorse,

While Six Millions Died

, London, 1968, p. 211; H.H. Heingold,

The Politics of Rescue

, New Brunswick, 1970, pp. 22-44.

*

E. Eearst, in

Wiener Library Bulletin

, April 1965; on Evian conference,

ibid.

, March 1961:

Sunday Express

, 19 June 1938.

†

A. Aoestler,

Promise and Fulfilment

, London, 1949, p. 21.

*

Palestine Royal Commission Report

, Cmd. 5479, London, 1937, para. 82.

*

D. Den Gurion, ‘The Zionist Organisation and its Tasks’,

Zionist Review

, April 1936.

†

Stenographisches Protokoll der Verhandlungen des XIX Zionisten Kongresses

, Vienna, 1937, p. 84.

*

Weizmann,

Trial and Error

, pp. 361, 363.

†

Sefer Toldot Hahagana

, vol. 2, part 2, p. 654

et seq

; Sykes,

Crossroads to Palestine

, p. 184.

*

Palestine Royal Commission Report

, Cmd. 5479, London, 1937.

*

Jewish Agency for Palestine,

Memorandum to the Palestine Royal Commission

, p. 5.

†

Cmd. 5479, p. 143.

‡

Quoted in ESCO, vol. 2, p. 802.

§

Palestine Royal Commission

, Minutes of Evidence, London, 1937, p. 297 (mufti), pp. 310–15 (Auni Abdul Hadi).

*

Weizmann,

Trial and Error

, p. 383.