A History of the World in 6 Glasses (21 page)

Read A History of the World in 6 Glasses Online

Authors: Tom Standage

Ultimately, it was John Pemberton's death from cancer, on August 16, 1888, that enabled Candler to consolidate his control over Coca-Cola. Candler called the city's druggists together and delivered a moving and entirely insincere speech. Pemberton was not just one of Atlanta's foremost druggists, he declared, but a good man and close friend; he suggested that the druggists ought to close their shops on the day of Pemberton's funeral as a mark of respect. With this speech, and by acting as a pallbearer at the funeral, Candler succeeded in convincing everyone that he had Pemberton's best interests at heart, and that his version of Coca-Cola was, as it were, the real thing. Pretending that Pemberton had been a close friend was an outright lie. Yet in a way it became true retrospectively. For it is only thanks to Candler that Pemberton is remembered today at all. Without Asa Candler's efforts, Coca-Cola would never have become the success that it did.

Caffeine for All

When he first secured the rights to Coca-Cola, for a mere $2,300, Asa Candler regarded it as merely one of his many patent medicines. But as sales continued to grow—they quadrupled in 1890, to reach 8,855 gallons—Candler decided to abandon his other remedies, none of which was anything like as popular. Coca-Cola was even selling during the winter, outside the usual soda-fountain season. So Candler hired traveling salesmen to sell Coca-Cola to pharmacists in neighboring states, gave away more free tickets to lure new customers, and pumped money into advertising. By the end of 1895 annual sales exceeded 76,000 gallons, and Coca-Cola was being sold in every state in America. The company's newsletter boasted that "CocaCola has become a National drink."

This rapid growth was possible because the Coca-Cola Company only sold syrup; it did not sell the finished product of syrup mixed with soda water. Candler was strongly opposed to the idea of selling Coca-Cola in bottles, since he was worried that the drink's taste might suffer during storage. Expanding into a new city or state, then, simply meant striking deals with local pharmacists and then shipping the syrup and its associated advertising materials: banners, calendars, and other items that featured the company's red-and-white logo. Since Atlanta was a major hub on the nation's railway network, distribution was not a problem. And pharmacists liked the drink because it was profitable: Each five-cent Coca-Cola they sold only required one cent's worth of syrup, and most of the rest was pure profit. The Coca-Cola Company, in turn, could make the syrup for around three-quarters of a cent per drink, so it made a profit on every drink sold too.

Downplaying Coca-Cola's supposed medical attributes, a sudden shift in strategy, also helped to boost sales. Until 1895 it was still being sold as a primarily medicinal product—described as a "Sovereign Remedy for Headache" and so on. But selling Coca-Cola as a remedy risked limiting the market to those who identified with the symptoms it was supposed to cure. Selling it simply as a refreshing drink, in contrast, gave it universal appeal; not everyone is ill, but everyone is thirsty at one time or another. So out went the gloomy advertisements listing ailments and maladies, and in came a cheerier, more direct approach: "Drink Coca-Cola. Delicious and Refreshing." Where previous advertisements had aimed Coca-Cola at harried, overworked businessmen looking for a headache cure or tonic, the new advertisements recommended the drink to women and children. This change of emphasis was, it turned out, fortuitously timed. In 1898 a tax was imposed on patent medicines, a category which was initially deemed to include Coca-Cola. The company fought the decision and ultimately won exemption from the tax, but it could only do so because it had repositioned Coca-Cola as a drink rather than a drug.

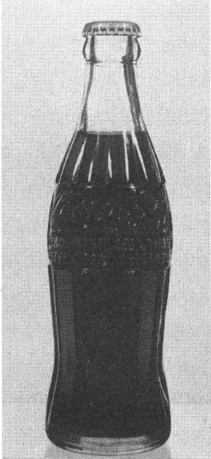

Sales were also driven, ironically, by the introduction of bottled Coca-Cola. Candler had always been opposed to the idea, but in July 1899 he granted two businessmen, Benjamin Thomas and Joseph Whitehead, the right to bottle and sell Coca-Cola. At the time Candler thought this was an unimportant deal, and did not even make the two men pay for the bottling rights; instead, he simply agreed to sell them the syrup, just as he sold it to soda-fountain owners. If bottling took off, he would sell more syrup; if it failed, as he expected, he would not lose anything. In fact, bottling proved enormously successful. Bottled Coca-Cola opened up entirely new markets, because it could now be sold anywhere—at grocery stores and at sporting events, for example—not just at soda fountains. Thomas and Whitehead soon realized that rather than doing the bottling themselves, it made much more sense to sell subsidiary bottling rights to others, in return for a large cut of the profits. In so doing, they created a lucrative franchise business and made Coca-Cola available in every town and village in the United States. The characteristic Coca-Cola bottle, with its distinctive shape, was introduced by the company in 1916.

Coca-Cola's distinctive glass bottle, introduced in 1916

Bottled Coca-Cola took off just as public concern was growing over the dangers of patent medicines, and harmful additives and adulterants in food. Leading the charge was Harvey Washington Wiley, a government scientist, who was particularly concerned about the danger posed by quack remedies to children. His years of campaigning were rewarded in 1906 with the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, generally known as "Dr. Wiley's Law." At first it seemed that the new rules would benefit Coca-Cola, which proudly advertised that it was "Guaranteed under the Pure Food and Drugs Act," by doing away with some of its more dubious rivals. But the following year Wiley announced his intention to investigate Coca-Cola on the grounds that it contained caffeine. His complaint was that, unlike tea and coffee, Coca-Cola, which was now available across America, was drunk by children. Parents were, he argued, generally unaware of the presence of caffeine and did not realize that their children were taking a drug.

Just as Kha'ir Beg had put coffee on trial in Mecca in 1511, Wiley put Coca-Cola on trial in 1911, in a federal case titled

The United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of CocaCola.

In court, religious fundamentalists railed against the evils of Coca-Cola, blaming its caffeine content for promoting sexual transgressions; government scientists expounded on the effects of Coca-Cola on rabbits and frogs; and expert witnesses put forward by the Coca-Cola Company spoke up in the drink's favor. The month-long trial made for great theater, with accusations of jury rigging and sensationalist coverage: "Eight Coca-Colas Contain Enough Caffeine to Kill," screamed one headline, entirely incorrectly. The problem with Wiley's case was that it was founded on moral rather than scientific objections. Nobody disputed that there was caffeine in Coca-Cola; the question was whether it was harmful, and to children in particular. The scientific evidence suggested that it was not. Besides, Wiley was not trying to ban tea or coffee.

So in the end the case came down to the narrow question of whether the Coca-Cola Company misrepresented its product, and whether it could claim that the drink was indeed "pure." Ultimately, the court found in Coca-Cola's favor: Its name accurately reflected the presence of kola, which contains caffeine. And since caffeine had always been part of the formula for Coca-Cola, it did not count as an additive—so the drink was indeed "pure." That said, this second part of the ruling was subsequently overturned on appeal, and an out-of-court settlement was agreed in which the amount of caffeine in Coca-Cola was reduced by half. The company also promised not to depict children in its advertisements, a policy it maintained until 1986. But the important thing was that the sale to children of CocaCola, a caffeinated drink, was now legally sanctioned. Together with the popularity of the bottled drink, this meant that CocaCola had successfully extended the use of caffeine, the world's most popular drug, into realms where coffee and tea had been unable to reach.

The Coca-Cola Company found other ways of selling its product to children without depicting them directly in advertisements. By far the most famous examples are the jolly posters depicting Santa Claus drinking Coca-Cola that first appeared in 1931. It is widely but wrongly believed that through these posters, the CocaCola Company was responsible for creating the modern image of Santa Claus as a bearded man in a white-trimmed red suit, choosing the colors to match its own red-and-white logo. In fact, the idea of a red-suited Santa was already firmly established. The

New York Times

reported on November 27, 1927 that "a standardized Santa Claus appears to New York children. . . . Height, weight, stature are almost exactly standardized, as are the red garments, the hood and the white whiskers. . . . The pack full of toys, ruddy cheeks and nose, bushy eyebrows and a jolly, paunchy effect are also inevitable parts of the requisite makeup." Putting Santa in its advertisements, however, enabled the company to appeal directly to children, and to associate its drink with fun and merriment.

The Sublimated Essence of America

The 1930s brought three challenges to the might of Coca-Cola: the end of Prohibition; the Great Depression that followed the Wall Street stockmarket crash of 1929; and the rise of a vigorous competitor, PepsiCo, with its rival drink, Pepsi-Cola. The resumption of legal sales of alcoholic drinks, which had been banned since 1920, was expected to have a particularly devastating effect on the sales of Coca-Cola. "Who would drink 'soft stuff when real beer and 'he-man's whiskey' could be obtained legally?" asked one press report. "Why, the case was an open and shut one: The Coca-Cola Co. was on the skids." In fact, the repeal of Prohibition had very little effect on sales; Coca-Cola, it seemed, met a different need from alcoholic drinks. Indeed, the range of circumstances in which it was consumed continued to expand.

For some people, Coca-Cola took the place of coffee as a social drink. Unlike alcoholic drinks, it was deemed suitable for consumption at all times of day—even at breakfast—and, of course, by people of all ages. During Prohibition, the company's brilliant publicist, Archie Lee, carefully pushed the consumption of Coca-Cola at soda fountains as a cheery and family-friendly replacement for drinking beer or other forms of alcohol in a bar, and a way to escape the gloomy reality of the economic climate. Lee also pioneered the new technology of radio to sell Coca-Cola, and the prominent placement of the drink in numerous movies—another way of associating it with glamour and escapism. CocaCola's advertisements depicted an appealingly happy, carefree world. As a result, Coca-Cola prospered during the Depression.

"Regardless of depression, weather, and intense competition, Coca-Cola continues in ever-increasing demand," noted an investment analyst at the time. Here was a hot-weather drink that still sold in the winter, a nonalcoholic drink that could hold its own against alcoholic beverages, a drink that made caffeine consumption universal, and an affordable treat that maintained its appeal even in an economic downturn. As Harrison Jones, a company executive, put it in a rousing speech that marked the finale of the company's fiftieth anniversary celebrations in 1936, "the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse may charge over the earth and back again—and Coca-Cola will remain!"

Some of these factors also helped Coca-Cola's rival, PepsiCola. Its origins went back to 1894, but after going through two bankruptcies it only became a serious competitor to Coca Cola in the 1930s, in the hands of a New York businessman named Charles Guth, who owned a chain of confectionery stores and soda fountains. Rather than buy Coca-Cola for his stores, he took over the ailing Pepsi-Cola company and offered its drink instead. Sales took off when he started to offer twelve-ounce bottles at the same price (five cents) that Coca-Cola charged for a six-ounce bottle. The larger drink cost very little more to make, since most of the cost was in bottling and distribution, and it had great appeal to cash-strapped consumers. A huge legal battle ensued as the Coca-Cola Company accused its rival of trademark infringement. The case dragged on for years, doing neither company any good, and prompting an out-of-court settlement in 1942. Coca-Cola agreed to stop contesting Pepsi-Cola's trademark, and Pepsi adopted a red, white, and blue logo that clearly distinguished it from Coca-Cola. Another outcome was that the word

cola

became a generic term for brown, carbonated, caffeinated soft drinks. Ultimately, the two firms benefited from each other's existence: The existence of a rival kept Coca-Cola on its toes, and Pepsi-Cola's selling proposition, that it offered twice as much for the same price, was only possible because Coca-Cola had established the market in the first place. The rivalry was a classic example of how vigorous competition can benefit consumers and increase demand.

By the end of the 1930s Coca-Cola was stronger than ever. Unquestionably a national institution, accounting for nearly half of all sparkling soft-drink sales in the United States, Coca-Cola was a mass-produced, mass-marketed product, consumed by rich and poor alike. In 1938 the veteran journalist William Allen White, a famous and respected social commentator, declared it to be "a sublimated essence of all that America stands for, a decent thing honestly made, universally distributed, conscientiously improved with the years." Coca-Cola had taken over the United States; now it was ready to take over the world, going wherever American influence extended.