A History of the World in 6 Glasses (19 page)

Read A History of the World in 6 Glasses Online

Authors: Tom Standage

A tea plantation in India in 1880. By this time, tea could be produced more cheaply in India than in China.

An expedition confirmed that tea was indeed growing in Assam, an obscure border region the company had conveniently invaded a few years earlier to provide a buffer against Burmese incursions into India. At the time, the company had decided to install a puppet king in the poorer region of upper Assam, while it concentrated on collecting taxes—on land, crops, and anything else it could think of—in lower Assam. Inevitably, the king did not remain on his throne for long once tea had been found growing within his territory. But turning Assam's wild tea plants into a thriving tea industry proved rather more difficult than expected. The officials and scientists in charge of establishing production bickered over the best way to proceed: Did tea grow best on the plains or the hills, in the hot or the cold? None of them really knew what they were talking about. Plants and seeds were brought in from China, but even the best efforts of a couple of Chinese tea workers, who accompanied the plants, could not induce them to flourish in India.

The problem was finally solved by Charles Bruce, an adventurer and explorer familiar with the people, language, and customs of Assam. By combining the knowledge of the local people with the expertise of some Chinese tea workers, he gradually worked out how to bring the wild tea trees into cultivation, where best to grow them, how to transplant trees from the jungle into ordered tea gardens, and how to wither, roll, and dry the leaves. In 1838 the first small shipment of Assam tea arrived in London, where tea merchants declared themselves very impressed by its quality. Now that the feasibility of producing tea in India had been established, the East India Company resolved to let others do the hard work. It decided to allow entrepreneurs in to establish tea plantations; the company would make money by renting out the land and taxing the resulting tea.

A group of London merchants duly established a new company, the Assam Company, to exploit this opportunity. Deploring the "humiliating circumstances" in which the British were forced to trade with Chinese merchants—this was just as the Opium War was about to break out—they jumped at the chance to establish a new source of production in India, since tea was "a great source of profit and an object of great national importance." A report drawn up by Bruce speculated, "When we have a sufficient number of manufacturers . . . as they have in China, then we may hope to compare with that nation in cheapness of produce; nay we might, and ought, to undersell them." The main problem, Bruce noted, would be finding enough laborers to work in the tea plantations. He blamed widespread opium addiction for the unwillingness of the local people to do such work, but confidently predicted that unemployed workers from neighboring Bengal would pour into Assam once they heard that jobs were available.

The Assam Company had no trouble raising funds; its share offering was hugely oversubscribed, with many would-be investors turned away. In 1840 it took control of most of the East India Company's experimental tea gardens. But the new venture was disastrously mismanaged. It hired all the Chinese workers it could find, falsely assuming that their nationality alone qualified them to grow tea. Company officials, meanwhile, spent the firm's money with wild abandon. The little tea that resulted was of low quality, and the Assam Company's shares lost 99.5 percent of their value. Only in 1847 did the tide start to turn after Bruce, by then the director of the company's operations, was fired. By 1851 the company had started to become profitable, and that year its teas were displayed to great acclaim at the Great Exhibition in London, a showcase for the might and riches of the British Empire. This proved, in the most public way possible, that one did not have to be Chinese in order to make tea.

A tea boom ensued as dozens of new tea companies were set up in India, though many of them failed as clueless speculators bankrolled new ventures without discrimination. Eventually, in the late 1860s, the industry recovered from this tea mania, and production really took off when industrial methods and machinery were applied. The tea plants were arranged in regimented lines; the workers were housed in rows of huts and required to work, eat, and sleep according to a rigid timetable. Picking the tea could not (and still cannot) be automated, but starting in the 1870s its processing could be. A succession of increasingly elaborate machines automated the rolling, drying, sorting, and packing of tea. Industrialization reduced costs dramatically: In 1872 the production cost of a pound of tea was roughly the same in India and China. By 1913 the cost of production in India had fallen by three-quarters. Meanwhile, railways and steamships reduced the cost of transporting the tea to Britain. The Chinese export producers were doomed.

In the space of a few years China had been dethroned as Britain's main supplier of tea. The figures tell the story: Britain imported thirty-one thousand tons of tea from China in 1859, but by 1899 the total had fallen to seven thousand tons, while imports from India had risen to nearly one hundred thousand tons. The rise of India's tea industry had a devastating impact on China's tea farmers and further contributed to the instability of the country, which descended into a chaotic period of rebellions, revolutions, and wars during the first half of the twentieth century. The East India Company did not survive to witness the success of its plan to wean Britain off Chinese tea, however. The Indian Mutiny, a widespread uprising against company rule that was triggered by the revolt of the Bengal army in 1857, prompted the British government to take direct control of India, and the company was abolished in 1858.

India remains the world's leading producer of tea today, and the leading consumer in volume terms, consuming 23 percent of world production, followed by China (16 percent) and Britain (6 percent). In the global ranking of tea consumption per capita, Britain's imperial influence is still clearly visible in the consumption patterns of its former colonies. Britain, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand are four of the top twelve tea-consuming countries, and the only Western nations in the top twelve: apart from Japan, the rest are Middle Eastern nations, where tea, like coffee, has benefited from the prohibition of alcoholic drinks. The United States, France, and Germany are much farther down the list, each consuming around a tenth of the amount of tea per head that is drunk in Britain or Ireland, and favoring coffee instead.

America's enthusiasm for coffee over tea is often mistakenly attributed to the Tea Act and the symbolic rejection of tea at the Boston Tea Party. But while British tea was shunned during the Revolutionary War, the American colonists' enthusiasm for the drink was undimmed, prompting them to go to great trouble to find local alternatives. Some brewed "Liberty Tea" from four-leaved loosestrife; others drank "Balm Tea," made from ribwort, currant leaves, and sage. Putting up with such tea, despite its unpleasant taste, was a way for American drinkers to display their patriotism. A small quantity of real tea was also covertly traded, often labeled as tobacco. But as soon as the war ended, the supply of legal tea began to flow again. Ten years after the Boston Tea Party, tea was still far more popular than coffee, which only became the more popular drink in the mid-nineteenth century. Coffee's popularity grew after the duty on imports was abolished in 1832, making it more affordable. The duty was briefly reintroduced during the Civil War but was abolished again in 1872. "America now admits coffee free of duty, and the increase in consumption has been enormous," noted the

Illustrated London News

that year. Meanwhile, tea's popularity declined as patterns of immigration shifted and the proportion of immigrants coming from tea-drinking Britain diminished.

The story of tea reflects the reach and power, both innovative and destructive, of the British Empire. Tea was the preferred beverage of a nation that was, for a century or so, an unrestrained global superpower. British administrators drank tea wherever they went, as did British soldiers on the battlefields of Europe and the Crimea, and British workers in the factories of the Midlands. Britain has remained a nation of tea drinkers ever since. And around the world, the historical impact of its empire and the drink that fueled it can still be seen today.

From Soda to Cola

Stronger! stronger! grow they all,

Who for Coca-Cola call.

Brighter! brighter! thinkers think,

When they Coca-Cola drink.

—

Coca-Cola advertising slogan, 1896

Industrial Strength

I

NDUSTRIALISM AND CONSUMERISM first took root in Britain, but the United States is where they truly flourished, thanks to a new approach to industrial production. The preindustrial way to make something was for a craftsman to work on it from start to finish. The British industrial approach was to divide up the manufacturing process into several stages, passing each item from one stage to the next, and using laborsaving machines where possible. The American approach went even farther by separating manufacturing from assembly. Specialized machines were used to crank out large numbers of interchangeable parts, which were then assembled into finished products. This approach became known as the American system of manufactures, starting with guns, and then applied to sewing machines, bicycles, cars, and other products. It was the foundation of America's industrial might, since it made possible the mass production and mass marketing of consumer goods, which quickly became an integral part of the American way of life.

The circumstances of nineteenth-century America provided the ideal environment for this new mass consumerism. It was a country where raw materials were abundant and skilled workers were always at a premium; but the new specialized machines allowed even unskilled workers to produce parts as good as those made by skilled machinists. The United States also mostly lacked the regional and class preferences of European countries; that meant a product could be mass-produced and sold everywhere, without the need to tailor it to local tastes. And the nation's railway and telegraph networks, which spread across the country after the end of the Civil War in 1865, made the whole country into a single market. Soon even the British were importing American industrial machinery, a sure sign that industrial leadership had passed from one country to the other. By 1900 the American economy had overtaken Britain's to become the largest on Earth. During the nineteenth century America focused its economic power inward; during the twentieth century the nation directed it outward to intervene decisively in two world wars. The United States then settled into a third, a cold war with the Soviet Union; the two sides were evenly matched in military terms, so the contest became one of economic power, and ultimately the Soviets could no longer afford to compete. By the end of the century, justly called the American century, the United States stood unchallenged as the world's only superpower, the dominant military and economic force in a world where different nations are interconnected more tightly than ever by trade and communications on a global scale.

The rise of America, and the globalization of war, politics, trade, and communications during the twentieth century, are mirrored by the rise of Coca-Cola, the world's most valuable and widely recognized brand, which is universally regarded as the embodiment of America and its values. For those who approve of the United States, that means economic and political freedom of choice, consumerism and democracy, the American dream; for those who disapprove, it stands for ruthless global capitalism, the hegemony of global corporations and brands, and the dilution of local cultures and values into homogenized and Americanized mediocrity. Just as the story of Britain's empire can be seen in a cup of tea, so the story of America's rise to global preeminence is paralleled in the story of Coca-Cola, that brown, sweet, and fizzy beverage.

Soda Water Bubbles Up

The direct ancestor of Coca-Cola and all other artificially carbonated soft drinks was produced, oddly enough, in a brewery in Leeds around 1767 by Joseph Priestley, an English clergyman and scientist. Priestley was first and foremost a clergyman, despite his unconventional religious views and a pronounced stutter, but he still found time to pursue scientific research. He lived next door to a brewery and became fascinated by the gas that bubbled from the fermentation vats, known simply at the time as "fixed air." Using the brewery as his laboratory, Priestley set about investigating the properties of this mysterious gas. He started by holding a candle just above the surface of the fermenting beer and noted that the layer of gas extinguished the flame. The smoke from the candle was then carried along by the gas, rendering it briefly visible, and revealing that it ran over the sides of the vat and fell to the floor. This meant the gas was heavier than air. And by pouring water quickly and roughly between two glasses held over a vat, Priestley could cause the gas to dissolve in the water, producing "exceedingly pleasant sparkling water." Today we know the gas as carbon dioxide, and the water as soda water.

One of the theories circulating about fixed air at the time was that it was an antiseptic, which suggested that a drink containing fixed air might be useful as a medicine. This would also explain the health-giving properties of natural mineral waters, which were often effervescent. Priestley presented his findings to the Royal Society in London in 1772 and published a book, titled

Impregnating Water with Fixed Air,

the same year. By this time he had devised a more efficient way to make his sparkling water, by generating the gas in one bottle from a chemical reaction and passing it into a second bottle, inverted and filled with water. Once enough gas had built up in the second bottle, he shook it to combine the gas with the water. For the medical potential of his work Priestley was awarded the Copley Medal, the Royal Society's highest honor. (Carbonated water was wrongly expected to be particularly useful at sea, for use against scurvy; this was before the effectiveness of lemon juice had become widely understood.)

Priestley himself made no attempt to commercialize his findings, and it seems that Thomas Henry, a chemist and apothecary who lived in Manchester, was the first to offer artificially carbonated water for sale as a medicine, sometime in the early 1770s. He followed the efforts to make artificial mineral waters very closely and was convinced of their health benefits, particularly in "putrid fevers, dysentery, bilious vomitings, etc." Using a machine of his own invention, Henry was able to produce up to twelve gallons of his sparkling water at a time. In a pamphlet published in 1781, he explained that it had to be "kept in bottles very closely corked and sealed." He also recommended taking it in conjunction with lemonade—a mixture of sugar, water, and lemon juice—so that he may have been the first to sell a sweet, artificially fizzy drink.

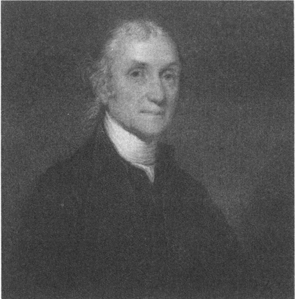

Joseph Priestley, who in 1772 published a book explaining how to make soda water.

During the 1790s scientists and entrepreneurs across Europe went into business making artificial mineral waters for sale to the public with varying degrees of success. Torbern Bergman, a Swedish scientist, encouraged one of his pupils to set up a small factory, but it was so inefficient that the woman employed to do the bottling had only three bottles an hour to seal. More successful was the venture established by a mechanic named Nicholas Paul in Geneva, in conjunction with Jacob Schweppe, a financier. Paul's method for carbonating the water was declared by physicians of Geneva in 1797 to surpass all others, and the firm was soon doing a thriving trade, even exporting its bottled water to other countries by 1800. Paul and Schweppe parted company and set up rival firms in Britain. Schweppe's firm produced more mildy carbonated water, which seems to have better suited British tastes; it was generally believed that water with fewer bubbles more closely imitated natural mineral water, and a cartoon from the period depicts drinkers of Paul's beverage as overinflated balloons.

Some of the new artificial mineral waters were prepared using sodium bicarbonate, or soda, so that

soda water

became the generic term for such drinks. They were strictly medical beverages until 1800; doctors prescribed them for various ailments, and they were considered a form of patent medicine by the British government, which imposed a duty of three pence on each bottle. One medical writer referred in 1798 to the "soda water" made and sold by Schweppe, and a London advertisement of 1802 states that "the gaseous alkaline water commonly called soda water has long been used in this country to a considerable effect."

However, soda water proved to be most popular in America. As in Europe, there was much scientific interest in the properties of natural mineral waters, and the possibilities of imitating them. The eminent Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush investigated the mineral waters of Pennsylvania and reported his findings to the American Philosophical Society in 1773. Two other statesman-scientists, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, also took an interest in the medicinal properties of mineral waters. The natural springs of Saratoga in upper New York State were particularly renowned at the time. George Washington visited them in 1783 and expressed sufficient interest that the following year a friend wrote to him to describe attempts to bottle the waters: "What distinguishes these waters . . . from all others . . . is the great quantity of fixed air they contain. . . . The water . . . cannot be confined so that the air will not, somehow or another, escape. Several persons told us that they had corked it tight in bottles, and that the bottles broke. We tried it with the only bottle we had, which did not break, but the air found its way through a wooden stopper and the wax with which it was sealed."

In the United States, soda water moved from scientific curiosity to commercial product with the help of Benjamin Silliman, the first professor of chemistry at Yale University. He went to Europe in 1805 to collect books and apparatus for his new department and was struck by the popularity of the bottled soda water being sold in London by Schweppe and Paul. On his return he began to make and bottle soda water for his friends and was immediately overwhelmed by demand. "Finding it quite impossible with my present means to oblige as many as call upon me for soda water, I have determined to undertake the manufacture of it on the large scale as it is done in London," he wrote to a business associate. He began selling bottled water in 1807 in New Haven, Connecticut.

Others soon followed in other cities, notably Joseph Hawkins in Philadelphia, who devised a new way to dispense soda water: through a fountain. Hawkins's aim was to imitate the spas and pump rooms built over natural springs in Europe, where the mineral water could be dispensed directly into glasses. According to a description of his spa-room from 1808, "The mineral water . . . is raised from the fountain or reservoir in which it is prepared under ground, through perpendicular wooden columns, which enclose metallick tubes, and by turning a cock at the top of the columns, the water may be drawn without the necessity of bottling." Hawkins was granted a patent for this invention in 1809. But the idea of selling soda water in spalike settings proved unpopular. Instead, apothecaries came to dominate the trade. By the late 1820s the soda fountain had become a standard feature of the apothecary's shop; the soda water was prepared and dispensed on the spot, rather than being sold in bottles (though bottled waters were imported from Europe, and Saratoga water was successfully bottled for sale starting in 1826).

Like so many other drinks before it, soda water started out as a specialist medicine and ended up in widespread use as a refreshment, with its medical origins granting it a comforting underlying respectability. As early as 1809 an American chemistry book noted that "soda water is also very refreshing, and to most persons a very grateful drink, especially after heat and fatigue." As well as being consumed on its own, it could be used to make sparkling lemonade, almost certainly the first modern fizzy drink. It was also being mixed with wine on both sides of the Atlantic by the early nineteenth century; one English observer noted that "when mixed with wine it is found that a much smaller quantity of wine satisfies the stomach and the palate, than wine does alone." Today we call this mixture a wine spritzer. But from the 1830s, and particularly in the United States, soda water was principally flavored using specially made syrups.

The

American Journal of Health

noted in 1830 that such syrups "are employed to flavor drinks and are much used as grateful additions to carbonic acid water." Syrups were originally handmade from mulberries, strawberries, raspberries, pineapples, or sarsaparilla. Special dispensers were added to soda fountains, which started to become increasingly elaborate. Blocks of ice were added to chill both the soda water and the syrups. By the 1870s the largest soda fountains were enormous contraptions. At the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, James Tufts, a soda-fountain magnate from Boston, displayed his Arctic Soda Water Apparatus. It was thirty feet high, towering over the spectators, and was adorned with marble, silver fittings, and potted plants. It was manned by immaculately dressed waiters and had to be housed in its own specially designed building. A testament to inventiveness and marketing prowess, this display generated plenty of orders for Tuft's American Soda Fountain Company.