A Durable Peace (3 page)

Authors: Benjamin Netanyahu

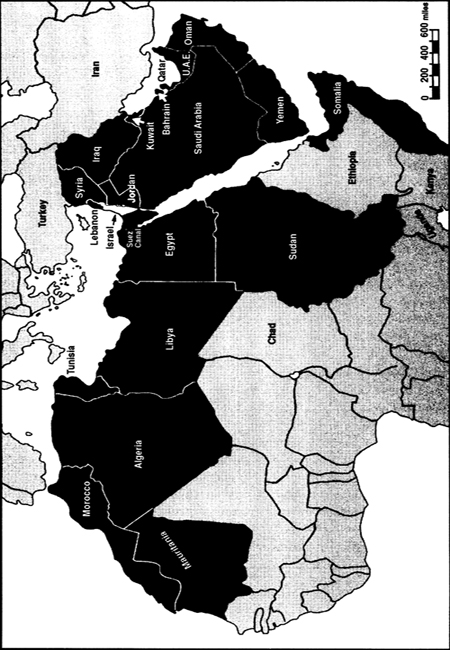

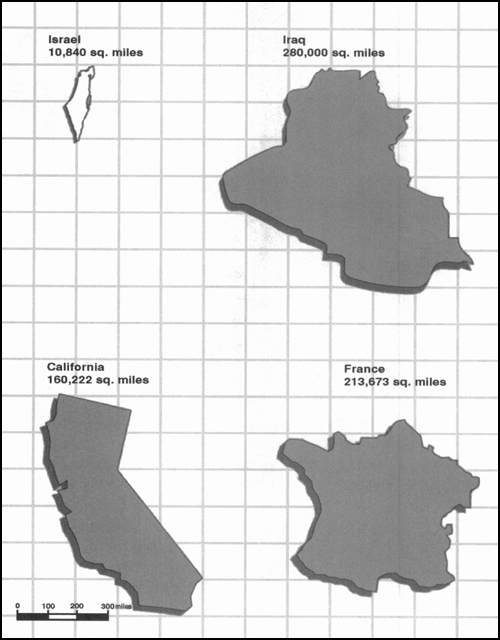

If an image of a country, its scenery, and its history is repeatedly implanted in people’s minds, it tends to assume overblown

dimensions. Contrary to the common view, this is not just the result of the distorting prism of television. Sunday-school

instruction a hundred years ago had a similar effect. Here is what Mark Twain wrote of his visit to the Holy Land in 1869:

I must studiously and faithfully unlearn a great many things I have somehow absorbed concerning Palestine…. I have got everything

in Palestine on too large a scale. Some of my ideas were wild enough. The word Palestine always brought to my mind a vague

suggestion of a country as large as the United

States…. I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having so large a history.

2

These lingering misimpressions are not limited to the geographic realities of Israel’s existence. They are matched by a widespread

lack of familiarity with the political and historical circumstances of Israel’s birth and its efforts to achieve peace with

its Arab neighbors. Twain, at least, knew the history of the land in considerable detail, and he was up to date on the contemporary

conditions of the Jewish people. This is not the case with many of those who shape, and receive, opinions about Israel today.

Over the last twenty-five years, since my days as an Israeli student in an American university following the Yom Kippur War,

I have had no choice but to engage in the Sisyphean labor of trying to roll back this boulder of ignorance, which has grown

increasingly heavy each year. For with each passing season, the facts of Israel’s emergence as a modern state, although readily

ascertainable in any library, recede further and further from memory. What has been inserted in their place is a facile misrepresentation

of reality. Moreover, there has been a growing tendency in the United States and in the West to use this distorted view of

Israel to explain away the region’s complicated conflicts. Many people have come to believe that all the turbulence of the

Middle East is somehow associated with the Jewish state. This is dangerous on two counts: It is losing Israel’s vitally needed

support abroad, and it has skewed Western policy away from a sober appraisal of Middle Eastern politics and of the danger

that this region’s endemic instability poses for the peace of the world.

This book is an attempt to restore to public awareness what were once evident truths to all fair-minded students of the region.

I have tried to focus on the main assumptions concerning the Arab-Israeli conflict and to analyze their truthfulness. I have

also concentrated on Israel’s current predicament—its position in the world, its internal administration, and its relationship

to the Jewish people worldwide—which is often glossed over in public discourse. Though I have used available historical material,

I do not intend this

to be a comprehensive chronicle of events. Nor is this a personal narrative, notwithstanding the references to my family that

appear in the text; in its own way, each Israeli household tells the story of Zionism, the movement for Jewish statehood,

and gives testimony to its unfolding saga. In the same vein, I have included experiences from my military service, diplomatic

postings, and work in government that can help the reader better understand why many Israelis have come to hold views similar

to my own.

The fact that they do hold such views may have been obscured by the victory of the opposition Labor party in the 1992 elections

over the Likud government, in which I served, and by the vocal opposition from the left to my own government, which came into

power in 1996. The ebb and flow of Israeli politics creates an impression of a great divide in Israel over every aspect of

national life. Nevertheless, the differences that divide Israelis on political matters are dwarfed by the enormous areas of

agreement that bind them together. The attentive reader will find that these disagreements over policy represent only a small

part of what is covered in this book. On most of the subjects, I believe my approach is representative of the views of the

majority of Israelis, wherever they fall on the political spectrum.

I write as an Israeli who wishes to see a secure Israel at peace with its neighbors, and who profoundly believes that peace

cannot be conjured up out of vapid pronouncements. Unless it is built on a foundation of truth, peace will founder on the

jagged rocks of Middle Eastern realities. Indeed, the Arab world’s main weapon in its war against the Jewish National Home

has been the weapon of untruth. For many people around the world, and for some in Israel itself, the fundamental facts of

this conflict have been distorted and obfuscated—about the nature of Zionism, the justice of its cause, the sources of the

Arabs’ intractable hostility to the Jewish state, and the barriers that have locked peace out of a violent region.

The Jewish people has had to contend with defamation for generations. But the scale of this century’s slanders against it

and

against Israel, their reach, effectiveness, and devastating consequences, have far exceeded anything seen before. Nevertheless,

I am convinced that these slanders can be refuted and the battle for truth can be won—that open-minded people

can

tell the difference between the endless calumnies leveled against the Jewish state and the unvarnished truth, when the facts

are presented before them.

When the battle for truth is won, it will open the way for an enduring peace between Arab and Jew. That such a peace can be

achieved I have no doubt. It will necessitate an understanding of the special conditions required to sustain peaceful relations

in the Middle East. I have attempted to spell out what such a peace would be like, and what changes are needed to produce

it—changes in Western policies toward the region, in Arab approaches to Israel, and in Israel’s own attitudes.

We are entering a historical period that portends both threat and promise. The old order has collapsed, and the new one is

far from established. The final guarantor of the viability of a small nation in such times of turbulence is its capacity to

direct its own destiny, something that has eluded the Jewish people during its long centuries of exile. Restoring that capacity

is the central task of the Jewish people today.

No one yet knows what awaits the Jews in the twenty-first century, but we must make every effort to ensure that it is better

than what befell them in the twentieth, the century of the Holocaust. The rebirth of Israel, its development and empowerment,

is ultimately the only assurance that such will be the case. More is at stake than the fate of the Jewish people alone. Since

biblical times civilization has been riveted by the odyssey of the Jews. If after all their fearful travails the Jewish people

will have rebuilt a permanent and secure home in their ancient corner of the earth, this will surely give meaning and hope

to all of humanity.

T

he reemergence of the Jews as a sovereign nation is an unprecedented event in the history of mankind. Yet for all its uniqueness,

one cannot truly understand the struggle of the Jewish people to bring the State of Israel into existence in isolation from

the universal longings of nations to be free. The rise of the Zionist movement to restore a Jewish state can be comprehended

only with reference to the more universal conflicts between nations and empires, between demands for self-determination and

the supranational ideologies of colonialism and Communism that have characterized the history of the last two centuries. It

is for this reason that the cataclysmic events at the close of the twentieth century will have a profound impact on Israel’s

future.

Seldom has the world witnessed such a spectacular disintegration as that of the Soviet Union. Shredded to confetti are the

Soviet dreams of global grandeur to be acquired through the assimilation of provinces from Eastern Europe to Latin America.

Equally remarkable has been the evaporation of the belief in Communism as the great organizing principle for world order and

human justice—a principle in which millions had vested a faith bordering on the religious. Such a dual collapse of the greatest

empire in history (in terms of territory) and the greatest “church” in history (in terms of the number of people under its

sway) cannot occur without unleashing political tidal waves that will wash over every nation and state in the world. It will

be impossible to make any sense of events without paying due attention to the unfolding search for a new organizing principle,

or principles, with which to assist in settling an unsettled world. Obviously, the focus of this search will first be on the

newly liberated Soviet republics and the countries of the former Communist bloc. But the arrangements that are devised to

meet the needs of these newly freed peoples will have far-reaching consequences for the rest of the world and for the ways

in which it will resolve its various disputes.

In the search for a new order, the international community is going back, almost against its will, to where it was before

it was so rudely interrupted by the rise of Communism. For the spread of Soviet totalitarianism and the resulting Cold War

was a glacier that buried beneath itself, in a state of invisible but perfect preservation, many of the great unresolved problems

of the nineteenth century. Of course, to some the nineteenth century did not seem problematic at all. After the decisive defeat

of Napoleon in 1815, it was perhaps the most peaceful century in two millennia—since the Pax Romana. The world was nicely

divided up among rival empires: no major wars, no major calamities. But underneath the calm surface of empire there was great

ferment. Historical tribal groupings, regional duchies, and medieval city-states were coalescing into nations across Europe,

and millions of people were moving from the hinterland to the rapidly industrializing and politically conscious metropolises,

processes that were to ripple from Europe into Asia and Africa in our own century.

The rise of nationalism in the nineteenth century clashed with the world order of the day, and the resultant national uprisings

were summarily put down in 1848, the brief Spring of Nations. But when the old order finally did collapse after World War

I, the various and often competing demands of nations for self-determination, and the problem of nationalism as a whole, required

an immediate solution.

Thus, following their victory in World War I, the Allied powers convened to launch a “new world order,” signing the Treaty

of Versailles, establishing the League of Nations, and promulgating President Woodrow Wilson’s doctrine of self-determination.

The Versailles Conference was actually only the first in a seemingly interminable series of international conferences held

between 1919 and 1923 to determine the “outcome” of World War I. Britain’s prime minister, David Lloyd George, one of the

chief architects of the postwar settlement, himself attended no fewer than thirty-three such conferences, the most significant

of which (for the Jews) were Versailles (beginning in January 1919), the First Conference of London (February 1920), the San

Remo Conference in Italy (April 1920), and the Sèvres Conference in France (August 1920).

1

For simplicity, I will refer to the decisions taken by the nations of the world at these various conferences as the Versailles

settlement.