A 1980s Childhood (23 page)

Authors: Michael A. Johnson

Every now and again we would be taken on an outing to the zoo, museum or seaside and we would all file on to a dated-looking orange and brown coach that was driven by a worryingly tired and harassed-looking driver. The school coaches invariably smelled of urine and vomit and had chewing gum on the seats and crude anatomical drawings scratched into the windows. Within five minutes of departure, one of the children would start to feel sick, while another child would have a nose bleed. After ten minutes, the first child would vomit over the child next to them and another child would suddenly decide they were bursting for a wee. A fourth child would then spill their orange juice on the floor, while the remaining children sang

The Wheels on the Bus

repeatedly until we reached our destination, only pausing occasionally to ask if we were nearly there yet.

On arriving at our destination, the teacher would count us off the coach only to discover there was an extra child from a different class that wasn’t meant to be there. Meanwhile, nose-bleed child, blood splattered down the front of their pristine white shirt, fainted because they were too hot and hungry. We would eventually make our way inside the zoo/museum and be given a clipboard and blunt pencil each so that we could answer some kind of worksheet; inevitably all the pencils would be lost by the time we had reached the first item on the sheet. By this time the rain would usually have started so the emergency cagoules were handed out and since more children were now feeling faint, we’d adjourn for lunch.

I obviously had my, somewhat industrial, government-issue packed lunch with donkey-meat sandwiches and would look on longingly as other children enjoyed a chocolate-spread sandwich, a packet of Ringos, a can of cherry Coke, a packet of raisins and a square of jelly. The warm can of cherry Coke would usually detonate upon opening, covering several children in a fountain of pink foam and leaving more pristine white school shirts ruined.

Having visited the remaining items on the worksheet, we would then head off to the gift shop which was the highlight of the day. Each child had a small amount of spending money, usually kept in some kind of purse or container on a string around their neck, which would be spent on scented erasers, polished stones, coloured sand or leather bookmarks with the name of the attraction printed on them. The children would be counted back on to the coach and the return journey would begin as vomit-child and nose-bleed child began to perform vigorously once more. At some point on the way back the coach would come to a screeching halt as a panicked teacher suddenly realised that the extra child from the other class was still in the gift shop.

Now you may think I am exaggerating with my description of school day trips, but I can honestly say that virtually everything I have described above actually happened, although it probably didn’t all take place on the same day.

My time at first school drew to a welcome close and in September 1986, after the seemingly endless summer holidays, I began middle school where I was destined to spend the remainder of the 1980s. Everything was different here: the teachers, the children, the lessons, even the playground games. I had only just settled into the swing of things at my first school, and now I was wrenched from my cosy classroom where I was one of the big kids and thrown into a school where the biggest children had body hair, and one hormonally active child had already begun to grow facial hair.

At the first school, our uniform had been pretty simple and casual: boys wore a blue shirt and the girls wore a blue dress. It didn’t really matter what type of shirt or dress it was, as long as it was mainly blue. Or white. And the boys had to wear grey shorts, or black shorts, or trousers. There was just one boy in our class who wore a blue and white striped tie that may or may not have been part of the uniform – no one really knew.

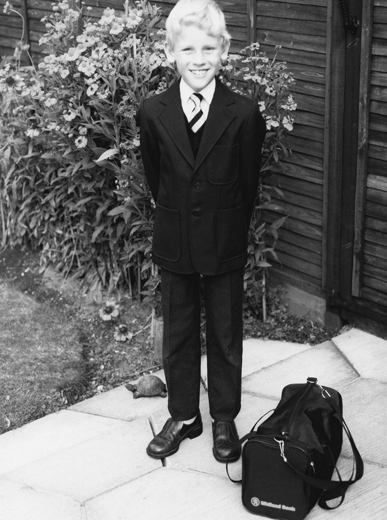

At the middle school, however, our uniform was a lot more disciplined and we had to wear black shoes, black trousers, black jumper, a white shirt and a black and white striped tie. For some reason, my parents decided to embellish upon this uniform by providing me with a black blazer to wear, which wasn’t part of the uniform and didn’t help me fit in at the school, especially since I was already looking distinctly odd wearing a pair of burgundy loafers and sometimes carrying a briefcase instead of a school bag. Fortunately, I managed to persuade my parents that the blazer was overkill and the burgundy loafers were toned down with the liberal use of some black shoe polish.

Ready for my first day at ‘big school’ dressed in a blazer that wasn’t part of the uniform and wearing burgundy-coloured loafers with a free Midland Bank school bag.

(Author’s Collection)

Now that we were at middle school we had proper science lessons with Bunsen burners and test tubes, we had geography lessons that taught us about oxbow lakes and plate tectonics, and we learnt about the effects of smoking and how to ‘Just Say No’ to drug pushers. I felt like a character from

Grange Hill

, but not one of the cool kids like Tucker, more like one of the nerdy ones that got pushed over in the corridor and had no idea where they were meant to be going and which class they were meant to be in. In fact, I remember sitting in the wrong lesson on more than one occasion with the dawning realisation that I didn’t recognise any of the other children in the room. Sometimes I sat through the whole of the wrong lesson, having no idea where else I should go, and on other occasions the teacher would spot me and send me on my way, leaving me wandering the corridors peering hopefully through the windows of the other classes looking for faces I recognised.

After finally locating the correct classroom, I was introduced to the exciting new concept of French lessons which taught us essential phrases and vocabulary to prepare us for a future cosmopolitan lifestyle. We were aided in our learning by the ever-popular textbooks called Tricolore, which featured a collection of French stereotypes living in La Rochelle on the west coast of France. The central characters were the Dhome family, who had a baker’s shop in the town, and they and their friends would most commonly be found in a local cafe ordering Orangina and ice creams and taking part in various vocabulary-expanding activities. As well as their somewhat unusual passion for Orangina, many of the characters in the Tricolore textbook were prolific letter-writers and liked to tell you all about themselves in writing.

Perhaps the best part of learning French was the role play sessions where we got to pretend that we were grown-ups on holiday in France with the exciting opportunity of ordering beer in a restaurant and being ‘married’ to the girl at the next desk.

One of the most welcome benefits of my transition to middle school was not having to eat the government-issue packed lunch since my new school had its own canteen staffed by a vast horde of cheery (and some not so cheery) dinner ladies. For the first time I was allowed to choose what I had for lunch and although I still had the low-income pink ticket, this could now be traded for food up to the value of 70p, which back in the mid-1980s was enough to buy you a three-course meal and a carton of milk. From what I understand, the majority of people do not have particularly fond memories of school dinners, but in comparison to the donkey-meat sandwiches I had endured for the previous four years, the canteen food was manna from heaven. Now I could (and did) order jacket potato with chips and a bag of crisps with a chocolate biscuit for dessert.

After we’d eaten lunch, the dinner ladies would usher us out into the playground for some fresh air and exercise, while a few of the more mischievous children would sneak back into the classrooms and hide to avoid going outside. We would often spend the whole lunchtime just peeking out from under a pile of bags and coats in the coat racks, occasionally ducking for cover to avoid the military patrols of the dinner ladies.

One of the dinner ladies once found herself rooted to the spot in the playground, completely unable to move, after discovering a condom on the ground. Thinking quickly she put her foot on it to hide it from the children and hoped to avoid drawing attention to it. Unfortunately, one eagle-eyed child had already spotted it and word quickly spread around the playground with the result being that within a few minutes, the dinner lady was surrounded by a crowd of inquisitive children asking her what was under her foot, what a condom was and why was she hiding it from them. Without any means of communicating her predicament to other members of staff, she remained in place for the majority of the lunch hour, red-faced and flustered trying to field a barrage of awkward questions.

When we weren’t menacing the dinner ladies we took part in normal playground activities for our age group: some children played ball games, others played chase, and a few others pretended they were lorries and spent the whole time ‘driving’ around the perimeter of the playground stopping occasionally to load or unload some new cargo. Another group of children battled it out with Top Trumps, while others traded Garbage Pail Kid stickers.

For those of you who have forgotten or blotted out the memory of Garbage Pail Kids, let me take a moment to remind you of them in all their disgusting glory. In 1985 the Topps Company began selling trading card stickers that were a parody of the hugely popular Cabbage Patch Kids. Each trading card featured a different Garbage Pail Kid with some kind of amusing wordplay name like ‘Adam Bomb’ accompanied by an illustration of the character usually in some kind of revolting scenario involving bodily functions or untimely deaths. The aforementioned example, Adam Bomb, was pictured sat on the floor pressing a detonator button as the top of his head exploded, revealing a mushroom cloud emanating from his skull. The Garbage Pail Kids gained enormous popularity very quickly and were traded in the playground for swapsies, for other toys or even for hard cash. Within a short space of time the craze had become an epidemic that swept the country and was ultimately banned from many schools because of both its unpleasant nature and the distraction it was causing.

Another short-lived playground craze saw nearly every child in the school practising their yo-yo skills with Coca-Cola-branded Russell Spinners, performing special tricks such as the Round the World, Walk the Dog and Rock the Baby. Coca-Cola had been using yo-yos, or spinners as they were otherwise known, as part of a worldwide advertising campaign for many years, but in 1989 a ten-week campaign in the UK resulted in sales of over 4 million Coca-Cola spinners. Red blazer-wearing spinner demonstrators started appearing in schools and shopping centres showing off their skills to the children, sometimes using two spinners simultaneously for extra coolness. Strangely, as children, we thought the demonstrators were cool despite the fact that they were often bearded, overweight, middle-aged men wearing dodgy-looking Butlinesque nylon blazers.

Every newsagent in the country now had at least one big promotional bin full of spinners and spare spinner strings for sale with instruction books on how to perform various tricks and posters advertising the forthcoming Spinner Championships. Over 15,000 competitions were held in high streets and shopping centres in every major town in Great Britain, with over 250,000 children taking part and ending with the National Finals, hosted by Jeremy Beadle at Alton Towers on 8 July 1989.

The yo-yo/spinner craze was short-lived and before long we went back to our traditional games of chasing people, kicking balls, chasing balls and kicking people. The playground games were usually punctuated with messages sent to and from the girls asking the boys who they fancied and if they wanted to ‘go out with them’. Sadly, I spent a lot more time being the messenger telling the girls who the boys fancied than being asked out myself. Dating for most of the children was a relatively new concept and I think few of us understood what was required or expected of us and so the majority of ‘couples’ just expressed their admiration for each other through a messenger, such as me, and then giggled when they saw each other. This would usually continue for a period of several weeks without any actual date taking place and, in most cases, without the ‘couple’ even speaking to each other. The relationship would often end in tears when one party decided they fancied someone else and would use the messenger (me again) to tell them they were now dumped.

Gradually, we started to get the hang of the dating game and before long some of the boys were holding hands with the girls and the girls began making the boys friendship bracelets. I wanted to get myself a girlfriend and so I worked on making myself more presentable. I began to wash myself more frequently using my Christmas gift soap-on-a-rope, added a liberal dusting of Hai Karate talcum powder and splashed on some of my dad’s Old Spice aftershave. I instantly became irresistible to women and attracted the interest of the prettiest girl in the class who agreed to go out with me after a lot of persuasion. The relationship was beautiful while it lasted, but alas, our love was short-lived and after just ten seconds, with no explanation, she said, ‘You’re dumped.’ Still, I could tell all my friends that I had dated the most popular girl in school and, no matter how brief the relationship, that was enough to put a very happy ending on my school days in the eighties.