A 1980s Childhood (18 page)

Authors: Michael A. Johnson

Despite his reputation, a bizarre set of circumstances resulted in Kenny delivering a ‘speech’ at the 1983 Conservative Party Conference, wearing his trademark giant foam pointing hands. He shouted to the assembled crowds, ‘Let’s bomb Russia!’ and ‘Let’s kick Michael Foot’s stick away!’, to which he received huge cheers from the audience. Everett then posed for photographs with a beaming Margaret Thatcher while still wearing his giant foam hands.

And what better way could there possibly be to close the chapter than with this surreal image in mind?

W

ORLD

E

VENTS

Thanks to

John Craven’s Newsround

, I’ve got a pretty good recollection of all the major events that happened around the world in the 1980s. The daily, child-friendly news reports kept me up to date with all the most important happenings from around the globe and explained them to me in a way that was simple to understand without being patronising.

Newsround

was the first British television programme to report the loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986 and was the first to report the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II in 1981. But as well as reporting on the tragedies, famines, wars and terrorism,

Newsround

showed us that good things were happening, too, and making the world a better place.

Newsround

told us about the fall of the Berlin Wall, the royal wedding between Prince Charles and Lady Diana, the World Land Speed Record attempt by Richard Noble and, for some reason, told us a disproportionately large amount about pandas.

Taking my cue from John Craven and the

Newsround

team, I have put together a selection of both the good news and the bad news that I remember from the eighties.

Poor old Michael Fish – he’s never going to live this one down, is he? On the evening of 15 October 1987 the nation watched Michael Fish deliver a reassuring weather forecast with the opening remark: ‘Earlier on today, apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way; well, if you’re watching, don’t worry, there isn’t.’

Just a few hours later, Britain was ravaged by the worst storm in nearly 300 years, claiming the lives of at least eighteen people, causing an estimated £7.3 billion worth of damage and serving up a large portion of egg on Michael Fish’s face. While the storm wasn’t technically a hurricane, it certainly had winds of hurricane intensity, with speeds of up to 134mph recorded at its peak.

I remember going to bed that evening and hearing the roof tiles lifting off the roof, the howling of violent winds and the crashing of objects being hurled around outside. The storm continued through the night and in the morning the full extent of the damage was evident. Our house remained largely intact with just a few roof tiles missing, but the garden was decimated with plants flattened and the fences blown down. Nearby, large swathes of trees had been uprooted and the streets were littered with debris. Across the country an estimated 15 million trees were flattened and many cars were crushed by falling branches. Boats were wrecked and run aground, the rail network ground to a halt and electricity supplies were cut off to several hundred thousand people.

The aftermath of the 1987 ‘Great Storm’. Scenes like this covered much of Britain the following morning.

(Courtesy of David Wright/Geograph project)

It took some weeks before everything returned to normal but the evidence of the storm can still be seen today in many forests where fallen trees continue to litter the landscape.

Just three days after the Great Storm had abated, an enormous international stock market crash occurred, hitting Hong Kong first then spreading to Europe and eventually the USA. In a very short space of time, the UK stock market fell 26.45 per cent which, although severe, was nothing compared to Hong Kong’s 45.5 per cent crash and New Zealand’s 60 per cent drop. Black Monday heralded the largest one-day percentage decline ever in the Dow Jones.

I won’t attempt to explain the causes of the crash beyond saying that it was most likely caused by something called ‘program trading’, where computers perform rapid stock executions based on external inputs, such as the price of related securities, and the scale of the crash was escalated by mass panic. I don’t pretend to understand the intricacies of the stock market, but I do know that a lot of people lost a lot of money that day, a few people made a lot of money and the repercussions were felt for years to come.

On 17 December 1983 a car bomb exploded outside the Harrods department store in central London, killing six people and injuring ninety others. The bomb contained around 30lb of explosives and was left in a 1972 blue Austin 1300 parked outside the side entrance of Harrods, on Hans Crescent, and was set with a forty-minute timer. At 12:44 a coded warning was given but it took over half an hour for police to arrive on the scene and tragically the bomb detonated just as the police officers approached the car. Three of the officers were killed, along with three passers-by, and ninety other people were injured.

My wife was in London on that fateful day, Christmas shopping with her parents and sister, and they had been into Harrods just a couple of hours previously. After stopping for lunch nearby, they decided to return to Harrods to buy something they had seen earlier. As they walked back along Brompton Road towards the store, they saw a police van speed past and commented to each other on the festive tinsel adorning the radio aerial. Minutes later, as they stood opposite the department store, they heard a tremendous ‘dead’ bang followed by a moment of shocked silence before people began screaming and running from the scene. It wasn’t until later that my wife, aged just 10 at the time, discovered that three of those policemen she had seen race past in their festively decorated van had been killed in the blast.

On every previous visit to London, my wife and her family had always parked their car right outside Harrods in the exact same spot where the bomb had exploded, but on this occasion my wife’s mother, a born-again Christian, had said she strongly felt the Lord was telling her not to park there. Not knowing the reason why, but being obedient to their faith, they parked near Hyde Park instead and were spared the disastrous consequences.

I remember being delighted when the news reports showed the first images of East and West German citizens joining forces to tear down the Berlin Wall in November 1989. As a 12-year-old child I had no real idea what the Berlin Wall was, why it was there, and why it was being torn down, but everyone else seemed to be excited about it so I joined in the celebration.

It wasn’t until some time later that I learned the Berlin Wall had been erected in 1961 as a way to completely separate the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) from the reputedly fascist elements of West Germany. In reality, the wall served to prevent the mass emigration and defection that had seen over 3.5 million East Germans flee into West Berlin during the post-Second World War period.

The tall concrete wall was 96 miles long and heavily guarded with over 300 watchtowers and bunkers; along with the much longer Inner German Border, the wall came to symbolise the Iron Curtain that separated Western Europe and the Eastern bloc during the cold war.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, November 1989. An East German guard speaks to a West German through a broken seam in the wall.

(Courtesy of Sharon Emerson/Wikimedia Commons)

In 1989 a series of radical political changes occurred in the Eastern bloc and after several weeks of civil unrest, the East German government finally announced that all GDR citizens were free to visit West Germany. Crowds of ecstatic East Germans climbed onto the wall and crossed over, joined by West Germans on the other side, and members of the public began to chip away parts of the wall with hammers. The governments later removed most of the rest of the wall and within the space of a year German reunification was formally concluded on 3 October 1990.

It is impossible to forget those haunting images of the starving Ethiopian people reported on BBC News by Michael Buerk in 1984. The devastating Ethiopian famine was claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children and many people felt moved to do something to help alleviate the suffering.

Boomtown Rats singer Bob Geldof was one of those people moved by the news reports and after calling in support from Ultravox front man Midge Ure, the pair penned the now-famous song

Do They Know It’s Christmas?

. Geldof created a group called Band Aid to record the track which featured many of the most popular British and Irish musicians of the time and when the single was released it shot to number one in the charts, where it stayed for five weeks, generating around £8 million for Ethiopian famine relief.

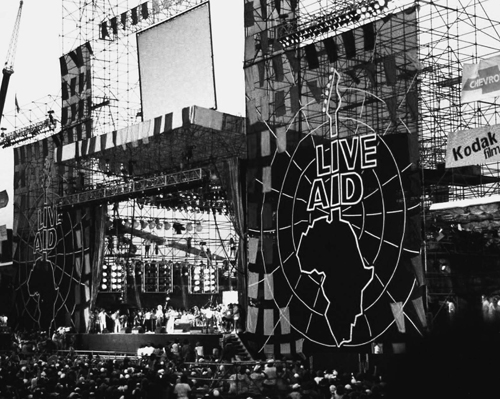

Following the success of the Band Aid single, Geldof conceived the idea of staging an enormous concert with all the biggest acts in the music business at the time. Although faced with numerous, seemingly impossible obstacles to staging a concert of this magnitude, Geldof managed to persuade dozens of acts to perform for free, and he arranged a live television broadcast that was watched by an estimated 1.9 billion people around the world.

Live Aid at JFK Stadium, Philadelphia, 1985.

(Courtesy of Squelle/Wikimedia Commons)

Two concerts were held simultaneously on 13 July 1985, one in Wembley Stadium and the other in the JFK Stadium in Philadelphia. Phil Collins famously performed at both concerts: starting with a gig at Wembley, he was then flown to Heathrow airport by Noel Edmonds in his helicopter to board Concorde. Thanks to the supersonic passenger jet, Collins crossed the Atlantic in time to perform at the Philadelphia concert as well.

Throughout the concerts, television viewers were urged to donate money via the Live Aid phone lines and seven hours into the concert, Geldof asked how much money had been raised. The answer was £1.2 million which reportedly disappointed and angered him and led to him marching to the BBC commentary box to make an appeal. Here he was interviewed by BBC presenter David Hepworth, who attempted to provide a list of addresses to which cheques could be sent, but the passionate Geldof interrupted him in mid-flow and shouted, ‘F**k the address, let’s get the numbers!’