(18/20) Changes at Fairacre (19 page)

Read (18/20) Changes at Fairacre Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place), #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place), #Autobiographical Fiction

'It doesn't look at it's best unfurnished,' I warned them, 'but at least it is all newly decorated upstairs, and you'll get some idea of size and outlook.'

It was a balmy afternoon, and the school-house garden was looking tidy. I still had the key, of course, by courtesy of the school governors, and water and electricity were still available. Our footsteps echoed hollowly on the bare boards and the uncarpeted stairs.

'This looks very monastic,' observed Horace in my old bedroom. He was looking at my lone bed, chair and electric heater. There were no curtains at the windows and no covering on the floor. Somehow it looked even more bleak than the completely bare rooms elsewhere, I realized.

I explained about the emergency arrangements.

'But I really think it's time to get the removal men to take these few things to the sale room. With luck, I'm not likely to need them again before the end of term, and anyway I must make other plans after that.'

After they had looked at the house, we sat on the grass in the sunny garden. A bold pair of chaffinches came close, hoping for peanuts. A lark sang high above us, and in the distance we could hear the bleating of Mr Roberts's sheep.

'It's a blissful spot,' said Eve.

'It is indeed,' agreed Horace, chewing a piece of grass lazily. 'It would be worth waiting for if you think it will really find its way on to the market.'

'Not for me to say,' I responded. 'But all the signs point that way. Sometime in the New Year, I imagine.'

We returned to Beech Green for tea. They were both very quiet on the journey there, obviously mulling over all that they had seen.

'And what's the village like?' enquired Horace when I had poured the tea. 'I suppose we should be looked upon as newcomers, and not really accepted.'

'That would depend on you,' I said. 'If you really want to join in, I've no doubt you would soon find yourselves president of this, and secretary to that, sidesman at the church, umpire at cricket matches, and a dozen other offices.'

'Well, we

would

like to join in,' said Eve roundly. 'I was brought up in a village, and it's one of the reasons we should like to make our home in one.'

'The only snag is,' added Horace, 'we should obviously have to be away most of the day, just like the rest of the village commuters. I suppose you have such bodies in Fairacre?'

'We do indeed. It's one of the more obvious changes in the village, and I really don't see what can be done about it. When I look back to my early days at the school, I can remember how close-knit the families were. I suppose Mr Roberts and his neighbouring farmer were the two main employers in the village, and I know there were the old familiar names on my school register which were in the log book almost a century ago.'

'And aren't there now?'

'A few. Nothing to speak of. So many have moved away, and when the cottages have become empty they have been sold for far more than the original village people could afford. It's happening everywhere. On the other hand, you can understand people wanting to bring up their children in the country, and if they have the money to pay for a suitable piece of property, and are game to have miles of travelling each day to work, who can blame them for buying village houses?'

'Like us,' commented Horace.

'The only objection I have,' I added, 'is that the children don't come to my school!'

'Take heart,' said Eve. 'They may come yet. After all, it's not going to close, is it? You told us that the other day.'

'It will be a miracle if it survives for another few years,' I replied soberly. 'I sometimes wonder if the authorities are waiting to see how low the numbers will fall, and if perhaps the whole property - school, school house and the ground - will then be put on the market. It would be a valuable property if that happened.'

'I noticed a shop in the village,' said Eve. 'Do you use it?'

'Indeed I do. It's the Post Office as well, and I suppose I do almost all my weekly shopping at Mr Lamb's, and get stamps and post things at the same time. Now and again I have to trundle into Caxley, mainly for clothes and the like, but I go as little as possible, parking gets worse and worse.'

'And is that the only shop?'

'Afraid so. Years ago things were different. Bob Willet was telling me the other day that when he was a boy there was a thriving blacksmith at the forge, a baker, a carpenter, a cobbler, a man called Quick - who was extremely slow - who was the carrier between local villages and Caxley. Fairacre must have been a busy place, and quite noisy too with plenty of horses about and the forge clanging away.'

'Sad, really.'

'The saddest part for Bob Willet was the demise of the old lady who used to keep the Post Office when he was young. She sold a few sweets, and home-made toffee was twopence a quarter. Guaranteed to pull out any loose teeth, too, in a far more enjoyable way than a trip to the dentist.'

'My favourites were gob-stoppers,' said Horace reminiscently. 'The sort that changed colour as you sucked them.'

'And mine were licorice strips,' continued Eve. 'My mother wouldn't let us have gob-stoppers. She said they were

common

!'

'Not common enough for my liking,' said Horace, 'on threepence a week pocket-money, I never got enough of them.'

And with such sweet-talk, the question of house-buying was shelved for the rest of the afternoon.

14 A Mighty Rushing Wind

AS we entered October the weather became very unsettled. There were squally showers, the wind shifted its direction day by day, and Mrs Pringle began to complain about the leaves which were making her lobby floor untidy.

Her complaints became even more strident when I proposed that the two tortoise stoves would have to be lighted.

'What? In this 'ere mild spell? I'd say the Office'll have a thing or two to say, if we starts using coke this early. It's tax-payer's money - yours and mine, Miss Read - as pays for the coke.'

'Children can't work in chilly conditions,' I retorted.

'Chilly?' shrieked Mrs Pringle. 'They'll be passing out with heat stroke, more like.'

Nevertheless, the stoves were roaring away the next day, and we were all the better for it. Except, of course, Mrs Pringle, whose bad leg definitely took a turn for the worse.

Bob Willet, who much enjoys our little fights at a safe distance, approved of the stoves being lit.

'We're in for a funny old spell,' he forecast. 'You noticed how early the swallows went this year? They knows a thing or two. And them dratted starlings is ganging-up already. Flocks of 'em in them woods down Springbourne way, messing all over they are, doin' a bit of no good to the trees.'

'Well, what does that mean?'

'Something nasty in the weather to come. That's what all that means. Birds know what to expect before we do. I'll lay fifty to one - that is if I was a betting man, which I'm not, as you well knows - as we'll have a rough day or two before long.'

I always take note of Bob Willet's prognostications. He is often right. But apart from the veering weathercock on St Patrick's church, all seemed reasonably normal on the weather front.

Or it seemed to be until midday on a fateful Wednesday. The dinner lady appeared, bearing a stack of steaming tins, and looking wind-blown.

'Coming over the downs was pretty rough,' she said. 'The wind's getting up. I heard a gale warning on the van radio.'

'I shouldn't take a lot of notice of that,' I said. 'Ever since that really dreadful gale two or three years ago, the weathermen have been only too anxious to give us gale warnings, and half the time they never materialize.'

'Well, we'll have to see. I know I'm going to be glad to get home today,' she replied, bustling away to her next port of call.

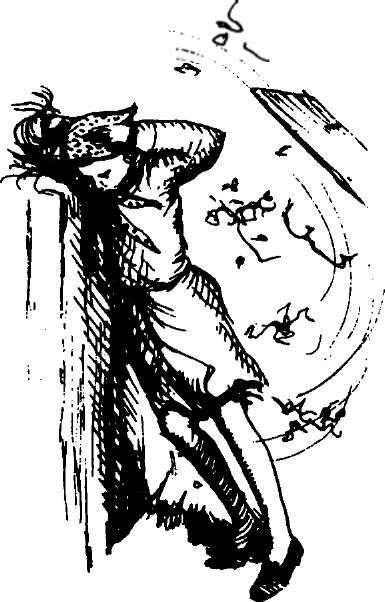

As the children tucked into macaroni cheese and sliced tomatoes, followed by apple tart and custard, the wind began to drum against the windows. Half an hour later, the gusts increased in intensity, and when I went across to the school house to see if all the doors were secure, I was blown bodily against my gate, and could barely get my breath.

It was at this stage that I saw the door of the boys' lavatory wrenched from its hinges and hurled towards the vicarage garden wall. I had a brief inspection of the school house exterior, decided that it was as safe as it could be in the circumstances, and struggled back to the school. Somehow the children must be evacuated to their homes before flying tiles and torn branches endangered us all.

Mrs Richards and I held a council of war as the windows rattled, and leaves and twigs spattered the panes.

Those who had a parent at home were dispatched at once, with strict instructions to run to safety and then to stay indoors. One or two others had telephones in their homes, and these we could forewarn about their children's early return. Several of them offered to pass on the message and mind neighbours' children with their own, until they returned from work.

It was lucky that the telephone lines were still intact, and I rang Mr Lamb at the Post Office to tell him that I was closing the school, and would he pass on the news.

'You're doing the right thing,' he assured me. 'I've just seen Roberts's tarpaulin blow off a straw stack across the road. Might have been a handkerchief the way it floated up!'

I also rang the vicar who said he would come at once with his car, and house any odd children (I had plenty of those, I thought) until their parents could collect them. Looking at the school clock, I said that I hoped I had not brought him from his lunch.

'Only from banana blancmange,' he said, 'and I don't like that anyway.'

Poor Mr Partridge, I thought replacing the receiver. I should have liked to have offered him a slice of our own excellent apple tart, but as usual it had all been polished off.

By a quarter to two, almost all our little flock had departed, and I said that I would run Joseph Coggs and his two younger sisters to their house before I made my way home to Beech Green. It had not been possible to get in touch with the Coggs' parents, but Joe assured me that Dad was off work (no surprise, this) and Mum got back from helping out at Mrs Mawne's at two o'clock.

Before I locked up, I put things to rights at the school, windows and doors secured, and tortoise stoves battened down, and saw Mrs Richards off towards her home.

The car was quite difficult to handle when the gusts hit it on my way through the village, but I deposited my passengers as Arthur Coggs opened the door himself.

He thanked me civilly, and although there was a strong smell of beer, past and present, he seemed comparatively sober, and I left my charges with a clear conscience. I then battled my way to Mrs Pringle's and told that lady not to attempt to go up to the school.

'It can all wait,' I shouted to her outraged face at the kitchen window.

'But what about them stoves? We should never have lit >_„ > 'em.

'I've damped them down.'

'And the washing-up?'

'Stacked on the draining board. That'll keep. Just

don't go out

!'

At this stage the window was all but wrenched from her grip. She gave a gasp, slammed it to, and I returned to the car to make my way home.

It was a frightening journey. The road was strewn with leaves and quite large branches from the trees, which were bowing and bending in an alarming way. There was an ominous drumming in the air which I had never heard before, and it was as much as I could do to drive a steady course along a road lashed with this hurricane-force wind.

About halfway home, I rounded a bend to encounter a damaged car, two others and an ambulance whose lights were flashing in warning. Two men were just sliding a stretcher into the shelter of the ambulance, and when it moved off towards Caxley, I saw how badly damaged the small car was.

The branch of a beech tree, thicker than a man's leg, had obviously been torn from the trunk and landed on the unfortunate driver's Fiesta. The two men had manhandled the branch to the side of the road, but although cars could just about pass, it was going to cause a hazard, especially when darkness came.

I wound down my window to shout any offer of help, but the two men assured me that the garage men were on their way.