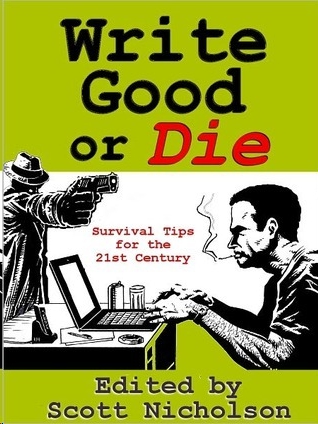

Write Good or Die

Authors: Scott Nicholson

Tags: #Authors, #book promotion, #books, #ebook business, #ebooks, #editing, #fantasy writing, #free download, #free ebook, #free writing guide, #freelance writing, #getting an agent, #heather graham, #horror writing, #ja konrath, #jonathan maberry, #kevin j anderson, #mj rose, #mystery writing, #novel writing, #publishing, #publishing industry, #romance writing, #science fiction writing, #scott nicholson, #selfpublishing, #thriller writing, #Writing, #writing advice, #writing career, #writing manual

Today, it is old-fashioned and seldom used

except in parody.

Second Person

The "you" tense. (e.g., "You walk down the

street, not knowing what you're going to find around the

corner.")

Largely experimental and only used for a very

specific kind of story.

Used by McInerney in

Bright Lights, Big City

to

show the character's drug-addled state.

Third Person Limited

Told through one character's viewpoint,

seeing just what that character sees and thinking just what s/he

thinks.

Can switch POV away from that character, but

the story should only be told through one character's viewpoint at

a time.

The POV usually breaks between chapters, but

can be done within chapters. However, the writer should give the

reader a visual indication that POV is being changed—just skip down

a few lines or give some other form of break.

Third person limited is the most-often-used

POV and the one that, by default, is the best choice for most

stories.

[I'm sure David had more to say on this

topic, but he ran out of time.]

Bottom line: In Morrell's judgment, most

first-person novels could be improved by a shift to the third

person. First person is very hard to do—harder than third person

limited—and should only be done with great care by the writer, and

only when the story demands it. Otherwise, especially for new

writers, they're probably better off going with third person.

David J.

Montgomery—http://www.davidjmontgomery.com

###

18. What’s In A Name?

By Scott Nicholson

http://www.hauntedcomputer.com

Shakespeare said, “What’s in a name? That

which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Gertrude Stein said, “A rose is a rose is a rose. “ John Davidson

said, “O which is the last rose? A blossom of no name.” An

adolescent Scott Nicholson once wrote a snarky line in a wretched

poem that went “A rose is a rose is a risen.”

So we could assume we could

name every character “Rose” and it would make no difference. Tokyo

Rose would be the same as Emily Rose, and

Rose Red

and

Rose Madder

could be interchangeable

titles in works by Stephen King. The character of “Rose” in the

world’s most popular movie, “Titanic,” could have been “Sue,” and

Johnny Cash’s song “A Boy Named Sue” could have been called “A Boy

Named Rose” and theoretically the universe would have continued

expanding intact.

But naming a character “Rose” doesn’t connote

blandness or homogeneity. The word comes loaded with a number of

associations: a flower notoriously challenging for the home

gardener; a pinkish-red color in the box of Crayolas; a food source

rich in Vitamin C; Shakespeare’s quote; an oft-used symbol for the

fleeting and ephemeral nature of love; and all the

Roses you have personally known, as well as

all the fictional Roses we encounter, whether the name is first or

last.

Names do matter, and one of the quickest ways

that fiction spoils itself is by having an unbelievable character.

You don’t want the name to throw up a speed bump for the reader.

The name should fit, go unnoticed and therefore easily accepted, or

else be an intentional ploy to draw attention. These last can be

tiresome: the big biker named “Tiny,” the pathetic loser called

“Romeo,” etc. The name doesn’t have to do all of the work of

character building, but it’s an important part of the package

deal.

Uncommon names are fairly common, as

evidenced by a quick thumbing through your local phone book. A

thirty-second scan of mine reveals Rollin Weary, Edward Wax, Oletta

Waycaster, Webb Weatherman, and Forest Weaver. These real names

would probably cause your reader to pause upon initial encounter.

This isn’t necessarily bad, but even real names can be loaded. If

your fictional Edward Wax is a candle maker or your Webb Weatherman

is a meteorologist, you’d better be writing comedy or satire.

One of the most common mistakes is making

your character name sound too “namey.” In other words, the name

sounds like that of a fictional character instead of a real person.

For all my admiration of Dean Koontz, his character names sometimes

sound artificial, as if churned out by some “random character

generator” (Jimmy Tock, Junior Cain, Aelfric Manheim, Martin

Stillwater, Harry Lyon, Joanna Rand). However, he is the only

writer skilled enough to name a serious character “Odd Thomas” and

get away with it.

A fanciful name, even if memorable, can turn

your readers away. My first encounter with Kurt Vonnegut was

through his short story “Harrison Bergeron,” in which the “bad guy”

is a woman named Diana Moon Glampers. I was a little too young to

grasp the subtleties of Vonnegut’s satire, and the name annoyed me

so much that I put off reading his work again for years. Now I

understand what he was doing, and I still remember that name though

I haven’t read the story since.

The sound of the name adds

tone to the character. While a stone-faced character might well be

called Stony, he’s probably more interesting if he’s a Chuck or

Dirk, which are both punchy, “hard” names (

Mystery Science Theater

fans may

remember “Biff McLargehuge”). A Richard is different from a Dick is

different from a Richie is different from a Ricardo. Sue is not

Suzannah, Suzie, or Susan. We expect an appliance repairman to be

named Danny, not Danforth, or Fred instead of Frederick. An

attorney or stockbroker will more likely be Charles than Charlie,

or Lawrence instead of Larry. We’d probably be more comforted to

have a doctor named Eleanor instead of Muffy, or an airline pilot

named Virginia rather than Brittany.

A character’s name is often the first and

most vital clue to a character’s ethnicity, which may or may not be

important to the story. Vinnie, Su, Ian, Darshan, Mohammed, Yoruba,

Yasmine, and Felicia are probably going to create reader

expectations. Names also carry generational weight: we envision

Blanche and Vivian as older, more serious people than we do Dakota,

Madison, or Mackenzie.

On the other hand, just as stereotypes are

often full of holes in real life, you can use expectations in a

delightful turn of the tables. Instead of a truck driver named Mac,

he can be Milton, a sociologist who enjoys traveling. Your New York

cabbie doesn’t have to be Armaan, who may or may not be a

terrorist; he can be Orlando, studying acting in night school. Just

make sure the people, and the motivations that propel them through

the plot, are valid.

Villains are in their own special nominal

class. Dracula is probably the perfect example. It’s practically

impossible to pronounce without sinister implications. Freddie

Krueger, Darth Vader, and Gollum are fraught with darkness. Stephen

King shines at this: Leland Gaunt, Randall Flagg, George Stark

(actually a pseudonym for writer Donald Westlake), Percy Wetmore,

and probably the best one of all, “It.”

Of course, King also gets

away with a character having the ubiquitous moniker “John Smith,”

but even this name choice serves a purpose, because King’s

protagonist in

The Dead Zone

is an everyman Christ figure. You probably don’t

want to call your soul-stealing, heart-munching bad guy “Bradley

Flowers,” though you might sneak that in as a mild-mannered, Walter

Mitty-type serial killer. Real-life killers like Charles

Starkweather and Richard Speck sound ominous, while other killers

like Albert Fish and Ted Bundy sound like somebody’s kindly uncle,

so your character names, like all other elements of your fiction,

have to be more real than reality.

Female names offer their own opportunities

for striking gold or striking out. “Thelma and Louise” are two

names that, to me, conjure up images of rough, trailer-trash women

(I have an aunt named Louise, so that obviously colors my

association). In the movie, they become self-reliant while

simultaneously depending on each other. Though they are doomed,

they are also strong survivors. I don’t think it would have worked

if the characters were “Cissie and Amber.” Save that for the

Cameron Diaz and Reese Witherspoon road movie.

In the 1950’s James Bond world, you could get

away with naming a character “Pussy Galore,” a lesbian who can be

“cured” into heterosexuality by the right hired gun. That won’t

work today, not even in genre fiction. Aside from the fact that the

great majority of book purchasers are female, you don’t want to

look stupid. Janet Evanovich’s cute, perky, yet often hapless

bounty hunter is named Stephanie Plum, while Kathy Reich’s tougher

and darker-edged forensic anthropologist is called Temperance

(Tempe) Brennan. You can tell just by the protagonists’ names that

the two series will have different tones.

A recent trend in genre novels is the

name-dropping of other writers. This immediately pulls me out of

the story, reminds me I am staring at the fabricated sentences of

an actual human being, and I have to fight past the “Nudge, nudge,

wink, wink” if I bother continuing at all. A manuscript I recently

read had a pair of juvenile delinquents named “Anthony Bates” and

“Norman Perkins.” As if this wasn’t painfully obvious enough, after

the introduction the characters repeatedly refer to one another as

Norm and Tony. I don’t think the association is worth the cost. If

it’s plainly an homage or tribute, then it’s fine, but it’s already

hard enough to keep the reader in a state of suspended disbelief.

Save that kind of thing for the acknowledgements.

So where do you get names? You can turn to

the phone book, but you’ll want to mix and match first and last

names so you don’t inadvertently create a character that’s too

close to home for some real person you’ve never met and who might

be litigious. I once encountered a real person who had the same two

names as one of my fictional characters, and it gave me pause.

Using local surnames can add authenticity if your fiction is set in

the area where you live. I often scour the obituaries because I use

a lot of rural characters with long local lineages. “Baby name”

books are great resources, especially if you have multicultural

characters, though you won’t always find help with surnames. The

Internet is an obvious and easy tool, and don’t forget your own

imagination.

Once you decide on a name, you can always

change it later, though having the name will help you start

building the character in your mind. Whichever name you choose,

sound it out, and make sure you want it in your story. See if it

matches the character and his or her personality and, more

importantly, actions. Especially if it’s the protagonist, choose a

name that can hold up for an entire story, book, or even a

series.

While the name you bestow on your character

may not be as important as the name you give your child, in some

ways your fiction is just as much an offspring of your life as is

your genetic contribution. Take it seriously, and make it

matter.

Scott

Nicholson—http://www.hauntedcomputer.com

###

19. The Three-Act Structure in

Storytelling

By Jonathan Maberry

http://www.jonathanmaberry.com

All stories are told in three acts, whether it’s a

joke, a campfire tale, a novel, or Shakespeare. The ancient Greeks

figured that out while they were laying the foundations of all

storytelling, on or off the stage.

Sure, there may be many act breaks written into a

script, or none at all mentioned in a novel, but the three acts are

there. They have to be. It’s fundamental to storytelling.

Here is the “just the facts” version of this.

The first act introduces the protagonist, some of

the major themes of the story, some of the principle characters,

possibly the antagonist, and some idea of the crisis around which

the story pivots. The first act ends at a turning point moment

where the protagonist has to face the decision to go deeper into

the story or turn around and return to zero. Often this choice is

beyond the protagonist’s control.

In the second act the main plot is developed through

action, and subplots are presented in order to provide insight into

the meaning of the story, the nature of the characters, and the

nature of the crisis. Also, supporting characters are introduced,

and we learn about the protagonist and antagonist through their

interaction with these characters. The second act ends when the

protagonist recognizes the path that will take him from an ongoing

crisis to (what he believes is) a resolution.

In the third act, the protagonist races toward a

conclusion that will end or otherwise resolve the current crisis

and provide a degree of closure. Most or all of the plotlines are

resolved, and the protagonist has undergone a process of change as

a result of his experiences.