What Hath God Wrought (53 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Jackson was fortunate that his time in office coincided with a wave of prosperity. Government revenues from tariffs and land sales soared, which made money available for both internal improvements and Indian Removal, even while retiring the national debt. The president and his party managed to reap the political benefits of a reputation for thrift and constitutional probity while at the same time passing “pork-barrel” legislation on a scale unprecedented. Both contemporaries and historians have noted the inconsistency (or, more charitably, the ambiguity) in Jackson’s policy on internal improvements. Adams had signed all bills for internal improvements in order to affirm their constitutionality and build support for economic development. Jackson, however, contrived to leave himself free to approve whatever projects he decided were “national” and veto those he decided were “local,” without any clear guidelines for distinguishing between them.

91

The one unambiguous consequence of the Maysville Road Veto was the doom of any comprehensive national transportation program. In the absence of such an overall plan, the Jackson administration felt free to distribute its favors where they would do the most political good. What Van Buren had learned fighting Clinton in New York, about how to posture as a friend of democracy while maintaining a tightly knit party machine and remaining completely flexible on economic issues, he put to use in Washington.

The internal improvements Jackson favored with federal appropriations included seacoast projects that might be called “external improvements”: dredging harbors and building lighthouses. Far from being suspicious of markets, the president sought to facilitate international commerce and promote the overseas marketing of American crops. One of the early achievements of his administration was the restoration of trade with the British West Indies. Adams, with his New England Federalist background, had to avoid any appearance of softness in dealing with Britain. Jackson, by contrast, could afford to be conciliatory. In pursuit of commercial benefits, America’s most famous Anglophobe courted British opinion: “Everything in the history of the two nations is calculated to inspire sentiments of mutual respect,” he now declared, with some exaggeration.

92

Advised by Secretary of State Van Buren and the Baltimore merchant-senator, Samuel Smith, Jackson and his emissary in London, the former Federalist Louis McLane, worked out a compromise accommodation that opened Canada and the British West Indies to U.S. goods. Democratic Republicans, including Old Republicans like Thomas Ritchie and South Carolina nullifiers like Robert Hayne, rejoiced at the commercial opportunities opened to American exports. National Republicans complained that Jackson had given up on trying to gain access to the West Indian carrying trade and noted that Adams could have had the same agreement if he had been willing to accept it. Indeed, the agreement partially sacrificed the interests of Yankee shipowners to those of agricultural exporters. The administration also signed a treaty obtaining more commercial advantages in the British Isles themselves. Of course, by far the most important of American export staples was cotton, and Britain was by far the best customer for American cotton.

93

When Britain took over the Falkland Islands off the coast of Argentina in 1833, the Jackson administration winked and did not allow this violation of the Monroe Doctrine to disturb cordial commercial relations.

On aspects of Anglo-American relations touching slavery, however, Jackson remained implacable. He refused to discuss any international cooperation to suppress the Atlantic slave trade, though all other maritime powers approved of it. He made no effort to accommodate British protests against the treatment of black West Indian sailors in southern ports. Indeed, whereas Monroe’s attorney general, William Wirt, had found the preventive detention of black seamen unconstitutional, Jackson’s attorney general, Berrien, declared it a constitutionally permissible exercise of state police power.

94

The Jackson administration sought out new markets in Russia, East Asia, and the Middle East for U.S. cotton, tobacco, and grain; it pursued the same objective with less success in Latin America. The navy was expanded, the better to protect American commerce. Responding to the killing of two American merchant sailors by a gang of thieves on Sumatra, Jackson dispatched the USS

Potomac

to the scene with 260 marines. In February 1832, Captain John Downes destroyed the Sumatran town of Quallah Batoo and killed over two hundred of its people, though he did not find the actual perpetrators of the crime. Many critics in the United States felt this an overreaction. In accordance with the wishes of the whaling industry, the administration also authorized the ambitious naval expedition commanded by Charles Wilkes that explored the South Pacific and Antarctic, although because of various delays the flotilla did not set sail until Jackson’s successor, Van Buren, had come into office.

95

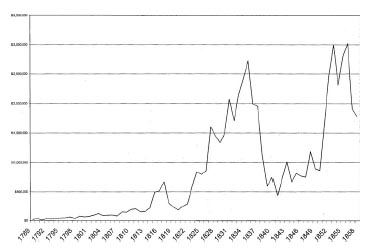

Federal Government Expenses for Internal Improvements, 1789–1858

This graph shows how much the federal government spent each year on transportation infrastructure, such as canals, roads, dredging of rivers and harbors, and lighthouses. It indicates a flurry of activity right after the War of 1812, then a marked increase during John Quincy Adams’s administration, which soared even higher during the administrations of Jackson and Van Buren until the Panic of 1837 curtailed government revenues and consequently expenses.

Graph prepared by Julia Ott from U.S. Congress,

Statement of appropriations and Expenditures…Public works

(Washington, 1882), 47th Congress, 1st session, Senate Executive Documents, vol. 7, no. 196 (U.S. Serial Set number 1992). Data here tabulated do not include expenses for public buildings, forts, armories, arsenals, or mints.

Jackson did not hesitate to pursue belligerent foreign policies on behalf of American commercial interests, even against major powers. His envoys gained over $7 million for American merchants in settlements of spoliation claims, mostly against France, dating back to the Napoleonic Wars. When the French Chamber of Deputies in the young July Monarchy balked at paying such a large bill, Jackson raged and threatened to license privateers to prey upon French shipping. Ex-president John Quincy Adams patriotically backed military preparations, but most of Jackson’s opponents were appalled. The French put their Caribbean fleet on a wartime basis and demanded that Jackson apologize, an unlikely occurrence. At the last minute (December 1835) the president’s advisors found a face-saving formula in which Old Hickory stated that he had not intended “to menace or insult the Government of France.” Satisfied, Louis Philippe’s ministry authorized payment. Whether tough or gentle, Jackson’s foreign policy was usually dictated by commercial interests, especially those of commercial agriculture—which Jackson the cotton planter understood at first hand. During the eight years of his nurturing administration, U.S. exports increased by 70 percent, imports by 250 percent.

96

The ambiguity or contradictions in the Jacksonians’ internal improvements record cannot be explained entirely by the hypocritical machinations of politicians. The mixed signals the administration sent apparently suited the mixed feelings of the American public toward the dramatic changes being wrought by the transportation and communications revolutions. On the one hand, the new economic opportunities were generally welcomed and widely seized. On the other, there were those with reason to fear economic transformations. Artisans, small farmers, and small merchants might find their accustomed local markets disturbed by the sudden intrusion of cheap goods from faraway places. Even some of those benefiting from economic development might worry about threats to local communities and traditional values.

97

Jackson’s mixture of appropriations and vetoes affirmed Old Republican principles of limited government while not requiring too much sacrifice of material advantages by his supporters in particular cases. Although unsympathetic to those who wanted the government to help create an integrated

national

market, his policies fostered

international

markets for American commerce. This distinction probably represented the clearest division in economic policy between Jackson and his opposition.

To judge by the views contemporaries expressed, misgivings about government involvement in the economy were much more widespread than misgivings about economic development itself. When Andrew Jackson visited Lowell, Massachusetts, he admired the technology of the textile mills and showed no concern over the social consequences of industrialization.

98

Perhaps his unconcern reflected the fact that the proletariat being created there was female. In any case, economic enterprise generally became controversial only when government became involved. Jackson’s election campaigns in 1824 and 1828 had warned against corruption, favoritism, and the perversion of democratic institutions; in office he continued to play upon these fears to discourage federal involvement in economic policymaking. In practice, however, the withdrawal of the federal government from transportation planning did nothing to prevent corruption or inefficiency at the state and local level; indeed, it made them even more likely. Involvement of government—local, state, or federal—in transportation projects helped in a society where large-scale mobilization of capital could be a problem. Most of the debate actually focused not on government intervention as opposed to free enterprise, but on whether only state and local authorities should promote the economy or the federal government play a role too. Doubts over the constitutionality of federal aid to internal improvements persisted throughout the antebellum era, often voiced by slaveholders determined to keep the central government weak lest it interfere with their peculiar institution. Those slaveholders who produced cotton had an additional motive for opposing federal internal improvements: If its expenditures could be held down, the government would have less need for tariff revenue. “Destroy the tariff and you will leave no means of carrying on internal improvement,” South Carolina’s free-trade advocate Senator William Smith declared in 1830; “destroy internal improvement and you leave no motive for the tariff.”

99

The Jackson–Van Buren practice of generous ad hoc appropriations coupled with professions of Old Republican strict construction pleased the friends of particular projects while reassuring slaveholders and staple exporters that the federal government was not being strengthened in principle or undertaking long-term, expensive commitments. Meanwhile, those who continued to believe in the benefits of central economic planning rallied to the opposition. But unfortunately for Adams and Clay, the very popularity of internal improvements hampered federal planning for them. With each region vying with every other for economic advantage, it seldom proved possible to forge the kind of coalitions necessary to legislate in favor of transportation at the national level. Responding to geographical competitions, the expenditures of state and local government to subsidize internal improvements dwarfed those of the federal government, even under Jackson. For the entire period before the Civil War, state governments invested some $300 million in transportation infrastructure; local governments, over $125 million. Direct expenditures by the federal government on such projects came to less than $59 million, though this does not count the substantial indirect help the federal government gave to internal improvements through land grants, revenue distributions, and services rendered by the Army Engineers.

100

In his first two years in office, President Jackson had already begun to lay the foundations for the future strength of the Democratic Party and to define its character and policies for a long time to come. The spoils system became a powerful instrument for motivating political participation at the grassroots level. The Eaton imbroglio established the pattern that the Democratic Party would resist those who tried to impose their moral standards on the public—whether these related to sexual conduct, Indian affairs, slavery, or war. Indian Removal set a pattern and precedent for geographical expansion and white supremacy that would be invoked in years to come by advocates of America’s imperial “manifest destiny.” Harder to pin down was Jackson’s attitude toward economic development, but it seemed that he supported the expansion of American commerce and markets, so long as this did not require partnership between the federal government and private enterprise in mixed corporations or long-term, large-scale economic planning. Jackson’s hostility to mixed corporations would become much clearer shortly, in his dramatic conflict with the National Bank. His ambiguity on the issue of federal aid to economic development would remain characteristic of the Democratic Party and lead eventually to fierce internal squabbles that pitted the dominant southern wing, determined to keep the central government limited and inexpensive, against northern Democrats eager for internal improvements and tariff protection. But as long as Jackson himself was in the White House, he remained very firmly in charge of both his party and the executive branch.