What Hath God Wrought (114 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

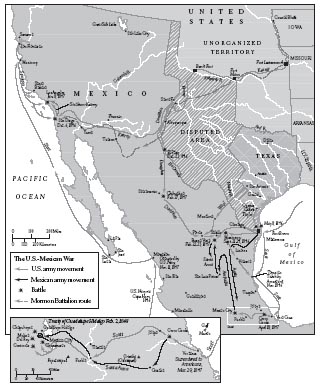

To mount Scott’s operation required diverting troops and resources from Taylor’s army. Although Scott tried to explain this to Taylor in person, he got delayed en route to northern Mexico, and the two generals missed connections. Taylor was bound to be disappointed in having the principal operations shift to another theater and another commander, and now he saw his best and most experienced units ordered away. The resentment he felt toward Scott compounded and complicated the suspicion with which he already regarded President Polk. With the armistice over, Taylor pushed ahead to Saltillo and then south to a position near a hacienda called Buena Vista.

Mexican partisans ambushed a courier bearing the plans for the transfer of units from Taylor to Scott, and thus Santa Anna became aware both of the impending attack on his capital and that Taylor now commanded a shrunken force consisting almost entirely of green volunteers. A cautious general would have responded by concentrating forces to defend Veracruz and Mexico City. Instead, eager to show his people a victory, the

caudillo

amassed the largest armed force he could—about twenty thousand men plus many camp followers—and moved them north to crush Taylor’s depleted army. (Raising the troops proved difficult, for only a few Mexican states supplied their full quotas; borrowing the money to fund the offensive was even harder.) Departing from his headquarters at San Luis Potosí on January 28, 1847, Santa Anna’s levies marched first through winter sleet and then through desert heat, with confusion, poor logistical support, and less than half the artillery their table of organization stipulated. When they reached Taylor’s vicinity, having taken three weeks to come three hundred miles, desertion and attrition had reduced their number to about fifteen thousand effectives. Warned of Santa Anna’s approach by a courageous Texan scout, the Americans fell back into a valley called La Angostura (the Narrows) where the Mexican numerical superiority would count for less. Taylor had about forty-five hundred troops, only a few of them, dragoons and cannoneers, being regulars. Meanwhile, Mexican cavalry under General Urrea made common cause with local partisans to interdict Taylor’s long supply line.

78

The retreating Americans burned some supplies to prevent their falling into enemy hands, and when Santa Anna came across the fires, he jumped to the conclusion that his opponents had fled in disorder. He therefore pushed his troops, tired from their long march, forward without rest into position to attack. Santa Anna then summoned Taylor to surrender in the face of overwhelming force; Old Rough and Ready responded, “Tell Santa Anna to go to Hell!” The reply sent in Spanish used more formal language but made his refusal clear.

79

It was February 22, George Washington’s Birthday, the American soldiers remembered. In preliminary fighting, the Mexicans won control of the high ground on their right flank. That chilly night, the two armies slept on their weapons, ready for further action.

The next morning, hoping to overawe his adversaries, Santa Anna staged a grand review of his army within sight of the U.S. lines (but outside of cannon range). There followed the war’s largest battle, named Buena Vista in the United States and La Angostura in Mexico. Both armies consisted largely of amateur soldiers with brief training and no combat experience. Both had suffered from desertions and logistical difficulties. The Mexicans had the advantage of numbers, the U.S. side that of tactical defense. In the morning the Mexicans renewed their assault on the defenders’ left flank, and in fierce fighting drove back the volunteers from Indiana, Arkansas, and Kentucky. One fleeing deserter encountered the formidable camp follower Sarah Borginnis and cried out that the battle was lost. But she “knocked him sprawling” (in the words of an eyewitness) and said, “You damned son of a bitch, there ain’t Mexicans enough in Mexico to whip old Taylor.” In fact, Old Rough and Ready had absented himself to check on his base in Saltillo; he returned at 9:00

A

.

M

. to be told by his second in command, John Wool, “General, we are whipped.” “That is for me to determine,” retorted Taylor; he immediately rushed the Mississippi volunteers commanded by Jefferson Davis, whom he had brought up from Saltillo, into the breach and plugged it. The glory Davis won that day would encourage him later to take a hands-on approach to his role as commander in chief of the armies of the Southern Confederacy.

80

In the nick of time, U.S. dragoons repulsed an attempt by Mexican lancers to encircle Taylor’s army. During the afternoon two more massive Mexican attacks on the American left flank halted in the face of superior U.S. firepower, notwithstanding the efforts of the

sanpatricios

manning Mexican artillery. When Taylor ordered a charge, however, his attacking units were decimated and repulsed. Cold rain fell. During the night, Taylor’s small army clung to their position and received some welcome reinforcements.

81

Santa Anna had pushed his soldiers to their limit. They were in no condition to renew their attack. Heavy fighting on top of forced marches had left them exhausted; many had scarcely had an opportunity to eat in the past two days, even though the

soldaderas

came up to the front lines to resupply them. During the night of February 23–24, the Mexican army silently withdrew, leaving campfires burning to fool their enemies. The next morning Taylor’s battered soldiers could hardly believe their good fortune. It had been, as Wellington said after Waterloo, “a near run thing.”

82

Santa Anna intended to renew the fight as soon as his soldiers had rested, but their heavy casualties and their commander’s obvious indifference to their welfare sent the desertion rate soaring. With his army melting away, Santa Anna’s officers persuaded him to begin the long march back to San Luis Potosí. The

caudillo

left behind more than two hundred of his wounded, but along the way he displayed U.S. cannons and flags his soldiers had captured early in the battle as evidence of what he claimed had been a victory. In truth, both armies had fought heroically and sustained heavy casualties: 746 on the U.S. side and about 1,600 on the Mexican. Death played no partisan favorites; American heroes killed included both Colonel Archibald Yell, former governor of Arkansas, Democrat and ardent expansionist, and Lieutenant Colonel Henry Clay Jr., son of the senator who had worked so hard for peace and who grieved that the young man had given his life in “this most unnecessary and horrible war.”

83

The Battle of Buena Vista constituted a tactical draw, but in its true significance a major U.S. victory, since Santa Anna had not succeeded, despite making a supreme effort, in destroying Taylor’s vulnerable force. Had Santa Anna won, he could have retaken much of northern Mexico, and the U.S. high command might well have aborted Scott’s campaign against Mexico City in order to shore up the defense of the Rio Grande. Some commentators feel Santa Anna should have renewed the attack after a brief respite; certainly his army sustained losses from desertion on the march back to San Luis Potosí as heavy as those another battle would have inflicted.

84

After the battle the Americans also withdrew. If Taylor had had more regulars available he might have tried pursuing, but instead he deemed it prudent to lead his army back to Monterrey to wait out the rest of the war. His volunteers had endured their baptism of fire and had proved themselves.

VI

Winfield Scott, one of the greatest soldiers the United States Army has ever produced, wore the stars of a general for more than fifty years, in three major wars (1812, Mexico, and the Civil War) and through several intervening frontier confrontations and campaigns, including Indian Removal and the Canadian rebellion crisis of 1837–38. Taken prisoner, exchanged, and later wounded in the War of 1812, Scott found himself celebrated for his individual exploits as well as for his judgment in command. The handsome, six-foot-four-inch Virginian became a brigadier general at the age of twenty-seven and won glory at the Battle of Chippewa in 1814, the sole American success on the Canadian–U.S. Niagara front. At the end of the War of 1812 only Andrew Jackson exceeded Scott in fame as a national hero. Both men had large egos, and not surprisingly within a few years they had developed a strong personal animosity. To the public, Jackson typified the frontiersman who took up arms when occasion required; Scott, on the other hand, typified the quintessential professional soldier, a less favorable image expressed in his unflattering nickname “Old Fuss ’n’ Feathers” (an allusion to the plumes on a general’s hat). Like so many others who shared his Whig political views, General Scott was a modernizer and an institution-builder. His nationalism took the form not of bellicose imperialism but of devotion to the central government and the rule of law. When the ultimate crisis came in 1861, Scott would choose not his home state but his country.

The military campaign from the Gulf to the City of Mexico represented the summit of Winfield Scott’s professional career; sixty years old in 1846, he had waited long for this opportunity. The landing at Veracruz constituted the most ambitious amphibious operation the United States armed forces would conduct before D-Day in 1944. Besides the formidable string of forts protecting Veracruz, planners had to take into account the fact that the port had no proper harbor and that it was prone to severe northern winds half the year and endemic yellow fever the other half. The difficulties brought out the best in Scott: his recognition of the importance of logistics, training, and staff work, his meticulous attention to detail. A perceptive biographer has suggested that he prefigured the military “technocrat.” Scott benefited from the services of Thomas Jesup, the army’s experienced quartermaster general; the two had had their differences, but both were conscientious professionals. Since President Polk insisted on waging war and cutting taxes at the same time, Scott and Jesup had to scale back requests and scramble to provide troops and supplies for the operation.

85

Invading Mexico from the Gulf required amassing an enormous flotilla of ships. The necessary cooperation between army and navy had a political as well as an interservice dimension. Beginning with Jackson, the Democratic Party had been friendly to the navy as protector of overseas commerce and international free trade, while the peacetime army had looked to the Whigs for support. (Significantly, it was Polk’s Democratic administration that founded the U.S. Naval Academy.) Fortunately, Scott developed good relations with the navy’s Gulf Squadron under Commodore David Conner and, after Conner’s retirement, Commodore Matthew Perry. The navy had already blockaded Mexico’s ports and welcomed an additional role. In November 1846, Commodore Conner occupied the Gulf port of Tampico without a fight, thanks to information supplied by Ann Chase, who took advantage of her British citizenship to live in the city as a U.S. spy. Working with a naval officer, Scott helped design a flat-bottomed landing craft to float the invasion troops onto the Mexican beach. Scott’s understanding of the potential contribution of the navy in combined operations would bear fruit again later in his “Anaconda Plan” for blockading the Southern Confederacy. Ironically, Scott succeeded less well in securing cooperation among the officers within the army itself, for his two regular subordinates, William Worth and David Twiggs, were bitter rivals, while Gideon Pillow, commanding the volunteers, was a Tennessee crony of Polk’s who shared his taste for intrigue and constantly worked to undermine Scott in the president’s eyes. But the general had selected a personal staff of outstanding ability, including Colonels Joseph Totten and Ethan Allen Hitchcock and Scott’s own favorite, Captain Robert E. Lee.

86

On March 9, 1847, only two weeks after Taylor had saved his army at Buena Vista, Scott’s armada of over a hundred ships delivered ten thousand U.S. troops to a beach three miles south of Veracruz and beyond the reach of its batteries. Santa Anna had not had time to bring his main force from San Luis Potosí to contest the landing, and Juan Morales, commanding the Veracruz garrison of only five thousand ill-trained militia, chose not to do so either. The Mexican general put his faith in the city’s stone defenses. A string of forts rendered Veracruz virtually impregnable by sea, while a wall fifteen feet high protected its landward side. Scott operated under a fixed timetable; he had to complete the reduction of Veracruz and move inland before the onset of the yellow fever season a month later. He had three options: to assault and take the city by storm, to besiege it and starve the occupants out, or to force a capitulation by bombardment. He chose the third course. Scott had long been mindful of the power of artillery; as peacetime general in chief, he had nurtured the mobile artillery that had proved so effective on the battlefields of Mexico. On March 22, Morales having declined Scott’s summons to surrender, U.S. mortars commenced firing shells over the walls of Veracruz and down into the city, wreaking havoc on military targets and civilians alike. But what Scott most wanted was to pound a breach in the city’s defensive wall. The government not having provided the heavy ordnance he had requested, Scott turned to his friends in the fleet. They did not care to risk their wooden ships in a firefight with the formidable seaward fortifications of Veracruz, but the navy lent Scott both guns and crews to ferry them ashore where they could batter the landward wall, the weakest point in the city’s defenses. The bombardment continued day and night. Sixty-seven hundred projectiles landed in the city, starting fires and inflicting over a thousand casualties, two-thirds of them civilian, including about 180 deaths. “My heart bled for the inhabitants,” commented Captain Lee, who had helped direct the cannon fire; “it was terrible to think of the women and children.”

87

By March 26, with the wall breached, the hospital and post office among the buildings hit, the population feeling abandoned by their government, and the many neutral civilians in the port city terrified, a flag of truce signaled the start of surrender negotiations. Three days later the Mexican troops marched out to be paroled (that is, allowed to go home after signing a promise not to fight anymore unless exchanged for U.S. prisoners).