Vodka Politics (25 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

From Peter’s twenty-year Great Northern War against Sweden, to Alexander I’s triumphant showdown with Napoleon, and to Nicholas’ fiasco in the Crimea, wars are costly—not only for the peasant conscripts who paid with their lives but also for the society that endured ever greater requisitions, impositions, and taxes. Even in peacetime the costs of repaying war debts and maintaining a standing army brought little respite for the people and ensured that vodka revenues would remain crucial to the state’s ambitions.

1

Yet by the mid-nineteenth century it was obvious that Russia’s outmoded political system—built on medieval serfdom and a corruption-generating tax farm—could no longer keep up with the industrializing and modernizing powers of Europe. The autocracy was besieged by reform pressures from European liberals, abolitionists, and temperance advocates, while Russia’s embarrassing military defeat in the Crimea finally triggered sweeping political reform. Yet even the death of serfdom and the tax farm could not kill the political dynamics of Russian vodka politics: the state’s thirst for revenue was unquenchable, and once again it would be society that paid the tab with its misery.

The Drunken Budget

Figuring out exactly how much vodka contributed to the imperial treasury sounds simple: just leaf through the archives of the finance ministry. The problem is that—like most European states—until 1802 Russia did not actually have a finance ministry or even a unified state budget. Instead, a hodgepodge of different institutions was empowered to both raise and spend revenues in the name of the tsar. Add to that the generations of monarchs who considered the land and people as their personal possessions, and suddenly untangling public (government) from private (royal) funds becomes difficult, and retroactively constructing a modern-looking “budget” becomes almost impossible. Of course it was the same entanglement of public and private through the vodka tax farm that bred Russia’s systemic corruption in the first place, as the state encouraged private tax farmers to profit handsomely from the collection of public taxes.

2

For the sake of simplicity, let’s consider just the two main revenue sources: direct and indirect taxes. The link between specific expenses and specific revenues was far more explicit then it is today, especially between military expenditures and direct taxes. To pay for war debts and maintain the army, after the Great Northern War with Sweden (1700–1721), Peter the Great replaced a tax on households with a poll tax—or “soul tax”—levied on every man (except the clergy and gentry) from the youngest baby to the village elder. Peter reasoned that the tax from 35.5 “souls” paid for each infantryman, 50.25 for each cavalryman, and so forth. The army itself collected the tax before later outsourcing tax collection to the same landowners who were already responsible for rounding up conscripts from among their serfs. But the poll tax was not reliable for the state: it was tough to collect across Russia’s vast territory, and its collection—often requiring military backup—was highly unpopular. Since any tax increase threatened to ignite a peasant rebellion, revenues from the poll tax were historically stagnant, since the size of the taxable population also was stagnant.

3

For the state at least, indirect taxes—including the

gabelle

on salt and the tax on vodka—were far easier to collect thanks to the tax farmers. They had the appearance of being voluntary rather than forced, and the amount of the tax was not visible: it was just simply hidden within the retail price. Peter’s salt tax was incredibly lucrative, but by the early 1800s, rising fuel and labor costs had turned the salt trade into a loss-making venture.

4

Vodka, by contrast, was easy money. Whether for religious, medicinal, or recreational purposes, liquor was always in high demand. Unlike the stagnant poll tax or the declining

gabelle

, the vodka trade was incredibly lucrative, and vodka revenues could be increased by simply raising the tax rate, encouraging greater consumption, or both. This inherent contradiction—that the financial power of the autocratic state rested on the debauching of its own people through

drink—was the ultimate deal with the devil. As historian John P. LeDonne argued, once the treasury was hooked on vodka, the government “could not escape the dilemma that in encouraging the nobility to produce and the masses to consume liquor, it contributed to the spread of drunkenness and moral turpitude in town and countryside alike. This dilemma remained with the Imperial government until its demise in 1917.”

5

Indeed, this is the essence of Russia’s autocratic vodka politics: this fundamental dilemma outlasted the tsarist empire to bedevil the Soviet empire and the present-day Russian Federation as well.

The state’s “big three” revenue sources were always the poll tax, the salt tax, and the vodka tax. From the few historical re-creations of eighteenth-century Russian finances that we have, already by 1724 the 900,000 silver rubles gained from the liquor trade constituted 11 percent of all government receipts, eclipsing the

gabelle’

s 600,000 rubles (7 percent) to be the biggest indirect tax source. By 1795 vodka’s contribution had grown to 17.5 million rubles, or fully 30 percent of the budget, while the salt trade

lost

1.2 million rubles. In 1819 receipts from the vodka trade eclipsed even direct taxes, and from 1839 until the empire’s death throes in the Great War, vodka consistently provided the single greatest source of revenue to the imperial treasury.

6

Yet, even in light of these staggering statistics, is it fair to characterize this as subjugation of the Russian lower classes? After all, the peasantry seemed all too willing to drink up and endure not just the vodka tax farm, but also the systemic corruption it created.

“To be under the will of a lord is a good thing for subjects [

muzhiki

],” claimed godfather of the

kabak

, Ivan the Terrible, “for where there is no will of the lord set above them, they get drunk and do nothing.” But it was not just the tyrannical Ivan who saw slavery as preferable to alcohol: an early-seventeenth-century Dutch visitor found the penchant for drunkenness as proof that the Russians “better support slavery than freedom, for in freedom they would give themselves over to license, whereas in slavery they spend their time in work and labor.” Ultimately, in Ivan’s era, alcohol and slavery were two sides of the same coin: when it came to amassing laborers, some were indentured by force, “others were merely asked to drink some wine, and after three or four cups they found themselves slaves in captivity against their will.”

7

But that was medieval Russia, well before the codification of serfdom in the Ulozhenie of 1649. What then? As it turns out, even foreign visitors from the eighteenth century found the same subservience of the enserfed classes through alcohol.

“The vice of drunkenness is prevalent among this people in all classes, both secular and ecclesiastical, high and low, men and women, young and old. To see them lying here and there in the streets, wallowing in filth, is so common that no notice is taken of it,” wrote Adam Olearius in the 1630s. Highlighting the class distinctions, he noted: “The common people, slaves, and peasants are so faithful to the custom [of drinking elites’ vodka] that if one of them receives a third cup and a fourth, or even more, from the hand of a gentleman, he continues to drink up, believing that he dare not refuse, until he falls to the ground—and sometimes the soul is given up with the draught.”

8

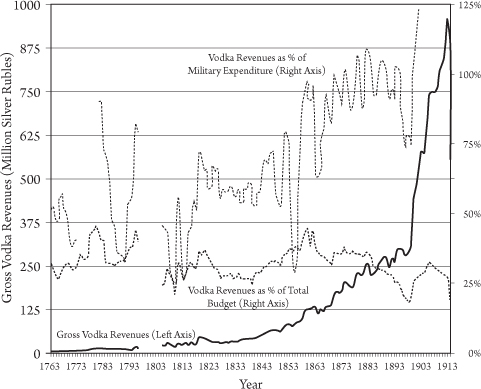

Figure 9.1

I

MPERIAL

R

USSIAN

A

LCOHOL

R

EVENUES

, 1763–1914

Sources

: Arcadius Kahan,

The Plow, the Hammer, and the Knout

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 329, 337; David Christian,

Living Water: Vodka and Russian Society on the Eve of Emancipation

(Oxford: Clarendon, 1990), 382–91.

Similar accounts of the people’s submissiveness to vodka litter the eighteenth century, too. In 1778 Englishman William Coxe described how a “benevolent” tax farmer—who had enriched himself by foisting vodka upon the peasantry—threw a liquor-infused public feast for his inebriate flock, who “crowded around the casks and hogsheads; and with great wooden ladles lapped incessantly wine, beer, and spirits. The confusion and riot, which soon succeeded, is better conceived than described; and we thought it expedient to retire. But the consequences of this feast were indeed dreadful.” He continued: “Many intoxicated persons were frozen to death; not a few fell a sacrifice to drunken quarrels; and others were robbed and murdered in the more retired parts of the city, as they were returning late to their homes. From a comparison of various reports, we had reason to conclude that at least 400 persons lost their lives upon this melancholy occasion. (The following day I counted myself no less than forty bodies, collected in two sheds near the place of entertainment.)”

9

By the early nineteenth century this system had long been entrenched—its human costs ever more apparent. “During the chilling blasts of winter,” begins Englishman Robert Ker Porter,

it is then that we see the intoxicated native stagger forth from some open door, reel from side to side, and meet that fate which in the course of one season freezes thousands to death.… After spending perhaps his last copeck in a dirty, hot

kaback

or public house, he is thrust out by the keeper as an object no longer worthy of his attention. Away the impetus carries him, till he is brought up by the opposite wall. Heedless of any injury he may have sustained by the shock, he rapidly pursues the weight of his head, by the assistance of his treacherous heels, howling discordant sounds from some incoherent Russian song; a religious fit will frequently interrupt his harmony, when crossing himself several times, and as often muttering his

gospodi pomilui

, ‘Lord have mercy upon us!’, he reels forward… and then he tears at the air again with his loud and national ditties: staggering and stumbling till his foot slips, and that earth receives him, whence a thousand chances are, that he will never again arise. He lies just as he fell; and sings himself gradually to that sleep from which he awakes no more.

10

In the early 1800s, foreign visitors moved beyond simply describing the drunken misery of the peasantry; they wanted to explain it, too. “The masses of the nation, the genuine Russians, still bears, in a very great degree, the stamp of northern barbarism,” wrote Hannibal Evans Lloyd in 1826. “They are a vigorous race, but rude, slavishly governed by the knout, almost

contented

with their melancholy degradation, grossly superstitious, and even without a notion of a better condition. The word of their priests, the images of their saints, and the brandy bottle are their idols.”

11

The irony was just as apparent as it was tragic: the more the serfs turned to vodka as an escape from their forced bondage, the more they became slaves to it.

Lest we be accused of patronizing orientalism in pointing out the pervasive drunkenness of the serf populations of Russia, it is worth mentioning that their additional enslavement to the bottle permeated Western countries as well. Consider American activist and orator Frederick Douglass: born into slavery in antebellum Maryland, the self-taught Douglass escaped to freedom in New York City in 1838 and quickly dedicated himself to the abolitionist cause. Published in 1845, his influential autobiographical

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: American Slave

—a riveting firsthand account of man’s inhumanity toward man—became a bestseller and a galvanizing call for emancipation.

In it, Douglass describes how the only respite from the backbreaking labor, whippings, and the master’s general cruelty came—as with their enserfed counterparts in Russia—during the holidays. “It was deemed a disgrace not to get drunk at Christmas,” Douglass explained, as it was “the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection.” He continues:

Their object seems to be, to disgust their slaves with freedom, by plunging them into the lowest depths of dissipation. For instance, the slaveholders not only like to see the slave drink of his own accord, but will adopt various plans to make him drunk. One plan is, to make bets on their slaves, as to who can drink the most whisky without getting drunk; and in this way they succeed in getting whole multitudes to drink to excess. Thus, when the slave asks for virtuous freedom, the cunning slaveholder, knowing his ignorance, cheats him with a dose of vicious dissipation, artfully labelled with the name of liberty. The most of us used to drink it down, and the result was just what might be supposed; many of us were led to think that there was little to choose between liberty and slavery. We felt, and very properly too, that we had almost as well be slaves to man as to rum. So, when the holidays ended, we staggered up from the filth of our wallowing, took a long breath, and marched to the field,—feeling, upon the whole, rather glad to go, from what our master had deceived us into a belief was freedom, back to the arms of slavery. I have said that this mode of treatment is a part of the whole system of fraud and inhumanity of slavery. It is so.

12