Vodka Politics (78 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

Before a bank of television news cameras at a ministerial meeting, an emotionless Medvedev announced that Kudrin’s “insubordination” was “inappropriate and inexcusable.” He went on.

Mr. Kudrin: if you don’t agree with the president’s policies—and it is the president’s policies that the government implements—you have only one choice, and you know yourself what that is: you should tender your resignation. So I will ask you right here: if you think that your view on the economic agenda differs from those of the president, you are welcome to write a letter of resignation. Naturally, I expect you to give an answer here and now. Are you going to resign?

Turning on his microphone, the stunned but steady finance minster replied: “Mr. President: indeed there are differences between you and me on some issues.” Figuring that he held the trump card by way of his strong personal relationship with Putin, Kudrin defiantly added: “But I will make a decision on your proposal after I consult with the Prime Minister.”

“You know what?” Medvedev continued, unbowed. “You can consult anyone you like, including the Prime Minister—but as long as I am president, decisions such as this one are up to me.” Medvedev added that, until his term as president ended and Putin’s began, “I’ll be the one making all the necessary decisions. I hope this is clear to everyone.”

58

And with that, the most audacious modern defender of Russia’s autocratic vodka politics, the reigning finance minister of the year, was gone by the end of the day.

“Drunken hooligans and thugs, every one”—the neighborhood thugs were always loitering in the courtyard where Vladimir Putin grew up. “Unwashed, unshaven guys with cigarettes and bottles of cheap wine. Constant drinking, swearing, fistfights—and there was Putin in the middle of it all.” Putin essentially grew up in Leningrad’s

Fight Club

, where the scrappy kid held his own against the biggest and the baddest. “If anyone ever insulted him in any way, Volodya would immediately jump on the guy, scratch him, bite him, rip his hair out by the clump.”

1

Coming from the mean, drunken streets, Putin developed an affinity for judo and sambo at a young age and the human cockfight that is mixed martial arts (MMA) later in life. When, in 2007, Russian heavyweight sambo champion Fedor “the Last Emperor” Emelianenko finally fought in Putin’s hometown of St. Petersburg, Putin sat ringside flanked by “the Muscles from Brussels”—Belgian kickboxing actor Jean Claude Van Damme—and Silvio “the Italian Rapscallion” Berlusconi. Putin, Van Damme, and Emelianenko later reconnected to kick off the Mixed Fight European Championship in Sochi in 2010, and when the Russian champ Emelianenko looked to end a three-fight slump against American Jeff “the Snowman” Monson at a packed Olympic Stadium in Moscow in late 2011, Putin again looked on approvingly from the front row.

Beamed live on the Rossiya-2 television channel, the no-holds-barred battle between these “two enormous sacks of rocks” (as David Remnick artfully described them), lasted the entire three rounds. An early-round kick broke Monson’s leg. Another ruptured a tendon, further limiting his mobility. A flurry of punches caused the fight to be stopped to tend to the blood pouring from the American contender’s mouth, which poured all over his anarchist and anti-capitalist tattoos. Still, online MMA aficionados panned the fight as “a bit of a snoozer.”

2

Each fighter’s corner was conspicuously emblazoned with the VTB logo of the fight’s primary corporate benefactor, Vneshtorgbank. At the end, both returned to their corners as trainers tended to their injuries—Monson’s being far more

apparent than Emelianenko’s—before the latter won by unanimous decision. Only then did Prime Minister Putin climb through the ropes to congratulate “the genuine Russian hero,” Emelianenko. What happened next was a shock to the cocksure Putin, who just two months earlier declared his intention to return to the presidency in the 2012 elections. Unexpectedly, yet unmistakably, Russia’s most powerful man was

booed

. Taken aback, Putin puzzled momentarily before continuing his judo kudos. During the previous twelve years in power Putin had never been booed by his own people. Now it seemed that his return for at least one (and, more likely, two) newly extended six-year presidential terms did not sit well with some. Something had definitely changed.

Suddenly, the global media took an interest in MMA, trying to gauge what just happened. Were they booing a bad fight, as Putin’s spokesman claimed? Were they booing the pre-fight singer, as the organizers claimed? Or were they booing the long lines at the bathrooms, as the pro-Putin youth movement

Nashi

claimed? As far as I can tell, MMA blogger Michael David Smith has never been one to take sides in Kremlin politics—or any politics for that matter—but it was clear even to him that “No one floating those alternate explanations has explained why, if that’s what the fans were booing about, they began their booing at the exact moment Putin began talking. And if the fans weren’t booing Putin, it’s hard to understand why Russian state television broadcasts felt the need to edit out the booing.”

3

From the other side of the blogosphere, anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny claimed that the booing heralded “the end of an epoch.” Navalny’s campaigns had brought him toe to toe with Putin’s regime: his re-branding of United Russia as “the party of crooks and thieves” resonated with a wide swath of a new Russian middle class that had grown tired of duplicity, corruption, and the bizarre, neo-feudal system of Putinism. The erosion of support could not have come at a worse time for the Kremlin: the December 2011 Duma elections were already upon them. Despite ratcheting up both nationalist rhetoric and pressure on independent monitors and critics, United Russia received only forty-nine percent of the votes—the party’s first ever backward step. Despite the frigid Moscow winter, first thousands, and then hundreds of thousands, of protestors condemned the vote rigging, ballot-stuffing, and biased media coverage that marked the “dirtiest elections in post-Soviet history”—suggesting that even United Russia’s forty-nine percent was a greatly inflated figure.

4

Even more telling, tens of thousands of Russians—part of an increasingly active civil society—trained to become election observers in polling stations throughout the country.

These “for fair elections” protests were the largest Russia had seen since the collapse of communism, leading many to wonder whether the autocratic regime would respond with repression and bloodshed. Thankfully, it did not. Despite a sizable security presence looming nearby, the largest protests between the

December 2011 Duma elections and the March 2012 presidential elections all passed without confrontation. Other signs of accommodation followed: the protests were reluctantly covered on state-run TV, and once-blacklisted opposition figures were allowed to air their grievances.

5

Outgoing President Dmitry Medvedev met with opposition leaders and even proposed liberalizing reforms, such as reinstating the direct election of governors. The state even promised greater transparency in the presidential elections by installing webcams to monitor each of Russia’s nearly one hundred thousand polling stations.

Whether the webcams deterred the widespread voter fraud of previous elections or simply pushed it off camera is still unclear. What is clear is that Vladimir Putin easily won the 2012 election, due primarily to his enduring popularity beyond the capital and the lack of an opponent who could unite the diverse streams of anti-Putin discontent. Nationalist posturing and promises of increased social spending further bolstered his appeal.

But while the opposition did not sink Putin, they certainly fired a warning shot across his bow. Where Russia goes in Putin’s third term and beyond will largely be determined by whether the Kremlin heeds the shot or ignores it.

History’s Revenge

With Satan at its center, the deepest circle of hell in Dante’s

Divine Comedy

is reserved for traitors. Just one step up in the eighth circle are the fraudsters: crooks, thieves, and corrupt politicians boiling in the sticky pitch of their own dark secrets. Alongside them are prognosticators and false prophets—their heads twisted backward, forever looking back on their failed predictions. So while we should perhaps tread lightly in making bold political prognostications, we can at least understand the constraints imposed on the Kremlin by Russia’s demographic past.

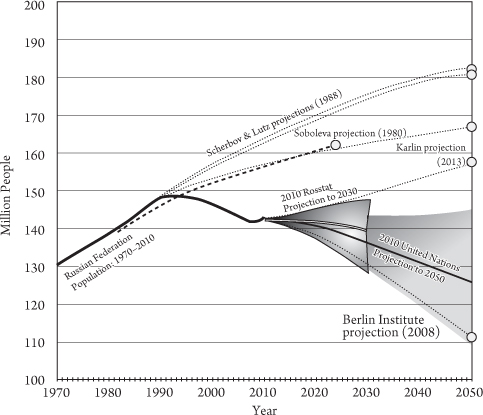

In 2010 the United Nations released its new long-term population projections. Despite such recent improvements as increased fertility and decreased mortality under Medvedev and Putin, Russia’s population will likely shrink from 143 million today to roughly 125 million by 2050 (

figure 24.1

). This would drop Russia from the seventh most populous nation to the eleventh—barely beating out Vietnam.

6

How do they come up with estimates so far into the future, and how can they possibly be reliable? Well, demographers consider fertility and mortality statistics for all age cohorts, figure in migration, and calculate a range of optimistic, pessimistic, and likely scenarios. As it turns out, these projections hit the mark ninety-four percent of the time.

7

When they miss, it usually is due to big surprises: the unexpected baby boom after World War II made earlier American projections look foolishly low. The grim reality of the HIV/AIDS epidemic made African population projections from the 1980s look far too rosy. And as

figure 24.1

shows, demographers from the 1980s could not foresee the demodernization that decimated Russia and its heavy-drinking post-Soviet neighbors.

Figure 24.1

R

USSIAN

P

OPULATION

P

ROJECTIONS TO

2050. Sources: Iris Hoßmann et al.,

Europe’s Demographic Future

(Berlin: Berlin Institute for Population and Development, 2008), 3; United Nations, “World Population Prospects, the 2010 Revision,”

http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/country-profiles/country-profiles_1.htm

(accessed March 17, 2012); Rosstat, “Izmemenie chislennosti naseleniya po variantam prognoza,”

http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/population/demo/progn1.htm

(accessed March 17, 2012); Sergei Scherbov and Wolfgang Lutz,

Future Regional Population Patterns in the Soviet Union: Scenarios to the Year 2050

, IIASA Working Paper No. WP-88-104 (Laxenburg, Austria: IIASA, 1988), 14–15; Svetlana Soboleva,

Migration and Settlement: Soviet Union

, IIASA Working Paper No. WP-80-45 (Laxenburg, Austria: IIASA, 1980), 130; Anatoly Karlin, personal correspondence, March 19, 2013.

Unlike the African AIDS epidemic, however, Russia’s demographic wounds were self-inflicted: the culmination of centuries of bad governance through vodka politics. The exhaustive 2009 study in

The Lancet

concluded that, were it not for vodka, Russia’s mortality figures would look more like those of Western Europe instead of resembling war-torn areas of sub-Saharan Africa.

8

Were it not for vodka, Russia could have at least escaped the gut-wrenching post-communist transitions of the 1990s with a healthier population—more like the Hungarians with their wine or the Czechs with their beer—instead of being mired in demographic decay.

Consider Poland: a neighboring hard-drinking Slavic nation with its own storied vodka traditions. Poland also suffered the pain of post-communist transition. Yet while Yeltsin and Putin ignored the vodka epidemic in the 1990s and 2000s, Poland consistently increased excise taxes on the far more potent vodka as part of a concerted effort to migrate to safer, fermented wines and beers. Partly as a consequence, Poland has not suffered the same demographic calamity that has befallen Russia. When communism collapsed in Poland, sixty-one percent of alcohol consumed was in the form of distilled spirits. By 2002, it was down to twenty-six percent. Even despite the “stress” of transition, male life expectancy in Poland jumped four full years. In Estonia, the proportion of alcohol consumed in the form of vodka dropped from seventy-two to thirty-three percent over the same time frame. Male life expectancy increased 1.5 years. Meanwhile, in the absence of a real alcohol policy in Russia, vodka’s share of alcohol consumption increased from sixty-six to seventy-one percent and male life expectancy plummeted by five years. Today, Poles and Estonians still drink a lot, but far less of it is in distilled forms like vodka. As a consequence, male life expectancy for both Polish and Estonian men is north of seventy years or a full decade longer than their vodka-soaked neighbors in Russia.

9