Vodka Politics (18 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

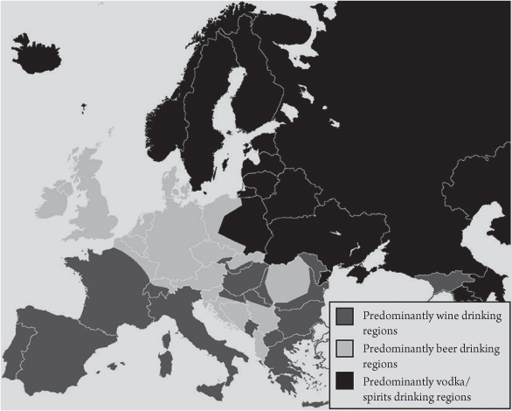

An unscientific “geoalcoholics” literature has built on such climatological determinism to map the dominant alcohol-consumption cultures of Europe. Climate indeed explains some of the map: the wine-drinking regions are mostly southern, Mediterranean climes where viniculture thrives. The so-called beer belt includes the grain-growing regions of central Europe, whereas a vodka belt encompasses what’s left: the Nordic and Baltic states, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and central and eastern Poland.

4

B

EER

, W

INE, AND

S

PIRITS

-D

RINKING

R

EGIONS OF

E

UROPE

. Adapted from Frank Jacobs, “442—Distilled Geography: Europe’s Alcohol Belts,” Strange Maps (blog), January 30, 2010,

http://bigthink.com/ideas/21495

.

Yet if we set aside the vineyards of the Mediterranean and look north, the climatological map looks eerily like a political map of nineteenth-century Europe. The differences in climate between Berlin and Tallinn, for instance, are not particularly stark—yet in the nineteenth century, while Berlin was the capital of the German Empire, Tallinn was ruled by Russian tsars. Tellingly, the westernmost frontier of the vodka belt that splits modern-day Poland is the exact border of the old Russian empire, suggesting that politics may be as important as climate in shaping drinking cultures.

Five hundred years ago there was no vodka belt. Back then, Russians brewed beers and fermented mead from honey. The well-to-do imported wines from more temperate climes. Tales of early Muscovite politics are steeped in inebriety, but it wasn’t vodka they were drinking.

5

Consider, for instance, the founding of Nizhny Novgorod (literally “Lower New-town”—now the fourth-largest city in Russia) on the banks

of the Volga River in 1222. Back then the middle Volga was populated by pagan Mordvinian tribes who, on hearing that Grand Prince Yury II of Vladimir-Suzdal was approaching down the Volga, dispatched a delegation with cooked meats and vessels of “delicious beer” to welcome the prince. Unfortunately, the young Mordva men of the delegation instead got drunk on the beer and devoured the meat, leaving nothing for the prince except earth and water. Interpreting this as a sign of submission—that all the tribes had to offer was their land and water—the prince rejoiced at his apparent conquest. And thus, as the story goes, “the Mordvan land was conquered by the Russians.”

6

Yet perhaps the most curious tale of alcohol in ancient Russia comes from the very birth of the Russian nation itself. Along with their eastern Slavic brethren the Ukrainians and Belarusians, Russians trace their lineage to Kievan Rus’. Kiev was the intellectual capital of Slavdom as well as the dominant power of Eastern Europe from the ninth through thirteenth centuries. It was there that legends of Russia’s origin were compiled into the

Povest’ vremennykh let

(

Primary Chronicle

), including descriptions of Russia’s conversion from paganism to Christianity.

7

At its height, the Kievan state stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, covering present-day Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, and the heartland of western Russia. Much of that territory was conquered by Grand Prince Vladimir the Great, who was renowned for his heathen debauches with his many wives. In a political calculation, neighboring princes and kings urged Vladimir to put away petty superstitions and adopt their modern faiths.

Vladimir agreed, sending forth fact-finding delegations to learn of different religious beliefs. Before long, Kiev was soon visited by ambassadors of the major monotheistic denominations to pitch to the great prince why he—and by extension his people—should convert to their faith. In the year 986 Vladimir hosted Jewish Khazars from the lower Volga, followed by papal emissaries from Germany who regaled the prince with tales of the power and grandeur of the Church of Rome. Greek scholars representing Byzantine Orthodox traditions took issue with the primacy of the pope before “Bulgars of the Mohammedan faith” arrived from the steppeland of the lower Don River and told the prince of the wondrous fulfillment of all carnal desires in the Islamic afterlife. “Vladimir listened to them,” according to the

Chronicle

, “for he was fond of women and indulgence, regarding which he heard with pleasure.” The Muslim Bulgars then described the rite of circumcision and the necessary abstinence from pork and wine. Furrowing his brow, Vladimir uttered a rhyme destined to be retold through the ages: “

Rusi est’ vesel’e piti, ne mozhem bez togo byti

.”

8

“Drinking,” said he, “is the joy of the Russes. We cannot exist without it.”

The following year, in the water of the Dnieper River, Vladimir and the subjects of Kievan Rus’ were baptized into the church of Constantinople, and the Russians have been Orthodox Christians ever since.

The point is that while Russia has a long history of inebriety, much of it did not include vodka. Moreover, even Russia’s long history of drunkenness isn’t unusual: Europeans of every region had been drinking nearly as long as the Russians, since before pasteurization alcoholic beverages were considered safer than milk, juices, and even water, which often transmitted disease-carrying microbes. (Incidentally, Louis Pasteur originally developed the pasteurization process to keep fermented beer and wine from spoiling.)

9

One could just as easily chronicle English history from the Roman introduction of beer brewing to the pagan Britons, perhaps recounting the murder of legendary fifth-century chieftain Vortigern at a drunken feast, or the death of King Henry I’s only son in 1120 when the

White Ship

was run aground by drunken sailors, or the legendary intemperance of Richard the Lionheart, James I, Charles II, and straight through to Winston Churchill.

10

Russia is hardly “oriental” in this regard: since the middle ages, all European nations drank heavily.

So if early Russians had so much in common with their beer- and wine-drinking European neighbors, what made them switch to vodka? Think about it objectively: colorless, odorless, and tasteless—it makes as much sense to drink vodka as rubbing alcohol. In recent years, the fastest-growing segment of the global alcohol market has been flavored vodkas.

11

From raspberry and huckleberry to chocolate and cookie dough, from waffles and doughnuts to bacon and smoked salmon, manufacturers are in a rush to make their products taste like anything

but

vodka. “The Frenchman will praise the aroma of cognac, and the Scotsman will laud the flavor of whiskey,” explains Russian writer Viktor Erofeyev. By contrast, “the Russian gulps his vodka down, grimacing and swearing, and immediately reaches for something else to ‘smooth it out.’ The result, not the process, is what’s important. You might as well inject vodka into your bloodstream as drink it.”

12

Why, then, would an entire nation come to prefer such a torturous drink over the more palatable beers, wines, and meads that predominated in Russia until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries?

13

This is not a trivial question. Geoalcoholic maps of European vodka, beer, and wine belts make it seem like the difference is simply a matter of taste—chalk it up to culture—but nothing could be further from the truth. Compared to traditional fermented beers and wines, distilled liquors were latecomers to the alcohol scene, but their arrival embodied a dramatic technological leap. As historian David Christian suggests, if beer and wine were like bows and arrows, vodka was like a cannon—an innovation with a potency unimaginable to traditional societies that would revolutionize both economy and culture.

14

The Political Foundations Of Cultural Practices

Rarely do we scrutinize the origins of cultural practices—it is far easier to just assume that they have always been that way or simply embody some inherent national trait. Why do Russians seem to have a weakness for vodka? The conventional explanation is that it is just part of being Russian—overconsumption is hardwired into their DNA. That’s wrong: what we assume today are essential cultural traits can often be traced to political and economic sources. Accordingly, I argue that the widespread, problematic drinking habits of today are actually the product of

political

decisions made during the formation of the modern Russian state over four centuries ago.

Going back, feudal Russia was starkly divided between the handful of local lords and the masses of impoverished peasants. Even before their formal enserfment by the

Sobornoye Ulozhenie

, or Law Code of 1649, most peasants were so indebted to the local landlords that they were already slaves in everything but name. Tied to their masters’ estates, few serfs ever ventured beyond their village. Each village had at least one tavern, or

korchma

, through which the feudal lords extracted the earnings of the peasants. Tellingly, the Ulozhenie also outlined the gruesome tortures for those caught bootlegging or otherwise undermining alcohol revenues.

15

Until the mid 1500s, village taverns were retail outlets for breweries located on the lords’ estate or in a nearby monastery. These

korchma

s offered traditional fermented drinks like beer, mead, and

kvas

—a low-alcohol drink made from black or rye bread. By the early sixteenth century, many taverns began adding vodka to their menus as just another drink option. This early vodka production was primitive and small-scale—distilling just enough for the local estate or tavern.

16

It quickly became clear that this early “burnt wine” (

goryachee vino

) or “bread wine” (

khlebnoe vino

) was a very lucrative business. The technology to distill vodka was basic and cheap.

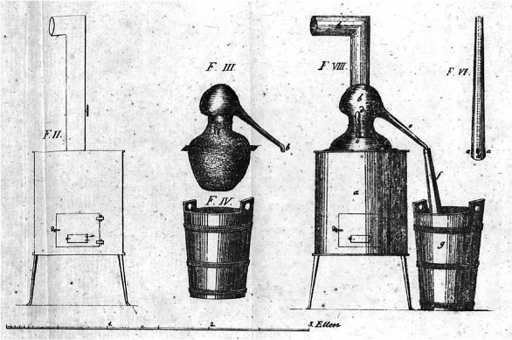

17

All that was needed was a simple still: a stove to heat a fermented mash and buckets to collect the concentrated alcohol as it condensed. The ingredients were plentiful: water from a local river or spring and rye or wheat from the local fields—which would be harvested at little cost to the landlord by his indentured peasants. And at the end of the day, the final product could be sold back to the peasants at a price that was tens or hundreds of times the cost of the raw materials. Advances in industrial rectification from the nineteenth century through today has made contemporary vodka, in the words of alcohol historian Boris Rodionov, “the most primitive and the cheapest (in terms of production costs) drink in the world”—certainly something to remember the next time you consider buying any bottle of top-shelf vodka for more than $10.

18

T

RADITIONAL

R

USSIAN

S

TILL

. It had a stove for heating the fermented mash (on left) and a funnel for the cooling and condensing of the alcohol, which was collected in a bucket (right). Riga, Neures Œkonomisches Repertorium für Liesland: 1814. Author’s personal collection.

Back in the sixteenth century, Muscovy was undergoing an agricultural revolution, adopting a three-field system of crop rotation that dramatically raised yields. What was a landowner to do with all that excess grain? He could send it to market—but with so much supply, prices were low, and the cost of transporting wagonloads of grain to market was high. A better option was to distill it into vodka, the price of which was high while the cost of transporting it was low: one horse-drawn cart could easily transport the vodka distilled from mountains of grain. Plus, unlike fermented beer or mead, vodka never spoils, so it is a constant store of value—a value that can be easily measured, divided, and sold by volume. For all of these reasons, vodka was the perfect mechanism for both commerce and extracting resources. For all of the doubt cast on Vilyam Pokhlebkin’s efforts to date vodka’s origins from this period, his resulting interpretation is astute, claiming that “if vodka had never existed, it would have been necessary to invent it, not from any need for a new drink but as the ideal vehicle for indirect taxation.”

19

And indeed it didn’t take long for the young Russian state to also appreciate vodka’s tremendous revenue potential.