Vodka Politics (16 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

As it turns out, not only

wasn’t

there such a legal dispute—there

couldn’t

have been, claims Peter Maggs, who has litigated international cases concerning iconic trademarks like “Smirnoff,” “Stolichnaya,” and even the likeness of the Hotel Moskva on the labels of Stoli.

26

“It is a very clear principle of international trademark law that a generic term cannot be protected,” he argues. “And if there ever was a generic term, it is ‘vodka’.”

27

If the question was not raised within the Comecon, the only other international legal institution that could have adjudicated such a dispute between these two communist countries was the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), which administers the main international laws regarding patents and intellectual property rights, including the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property that protects well-known trademarks. But “vodka” is not a valid trademark associated with

a particular producer, such as “Levi’s,” “Toyota,” or “Coca-Cola.” The Paris Convention also lacks mechanisms to arbitrate intellectual property disputes between countries, which helped prompt the creation of the modern World Trade Organization. “Furthermore,” Maggs continues, “almost all international commercial arbitration is over contract disputes, and a trademark dispute is not a contract dispute.”

28

Taken together, these accounts finally explain why, in this “high stakes” diplomatic tiff, Poland never actually put forth a legal defense of their position (which probably would be based on the appearance of “wodka” in Polish court documents in 1405 and their taxing of distilled spirits the following century) and indeed why most Polish authorities have no knowledge of this “case” that Pokhlebkin alone claims they lost.

29

Perhaps most remarkable about Pokhlebkin’s fabrications is how they have been elevated to the status of legend: standing above serious scrutiny for two decades. While we may devise all manner of hypothetical intrigues about why the eccentric Pokhlebkin felt compelled to weave such intricate lies—both about the substantive origins of vodka and the reasons for undertaking his investigation—unfortunately such questions are doomed to lie forever unsolved, alongside the mysterious murder of Pokhlebkin himself.

Back To Square One

If the unquestionable Pokhlebkin is now to be questioned, we are back to where we were before we entered the Vodka Museum at Izmailovsky Park, asking again: “where does vodka come from?” Fortunately, there are other theories.

Polish-American historian Richard Pipes has suggested Russians first learned distillation techniques from the Tatars of Asia in the sixteenth century. Whether by “pot distillation” where the alcohol was driven-out of fermented beverages in pots placed in a stove, or a “Mongolian still”—where they were left out to freeze so that ice could be removed from concentrated liquid alcohol—such indigenous experiments were crude. They were often fatal, too: producing highly concentrated “fusel oils”—poisonous liquids produced by incomplete distillation that are today used in industrial solvents and explosives. So it seems unlikely that vodka immigrated to Russia from the east.

30

Not all Russian historians agree with Pokhlebkin’s designated birthdate of vodka as 1478 or its birth place in Moscow. Some go back even further, dating vodka’s origins from the year 1250 in the ancient Russian city of Veliky Novgorod—the ancient trading outpost between the Hanseatic League and Byzantium. How did they come by this claim?

In the early 1950s, Artemy Artsikhovsky—head of the archeology department of the prestigious Moscow State University—excavated the soil around ancient

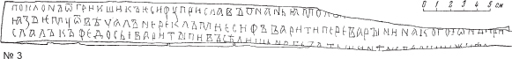

Novgorod. Deep in the waterlogged clay archeologists unearthed more than 950 well-preserved letters—written not on paper (as papermaking was not yet widely known), but etched into the bark of local birch trees. These resulting birchbark documents give a unique snapshot of everyday life in medieval northern Europe. Among these fragments of bark are numerous texts dating from the late 1300s (such as no. 3 and no. 689) that refer to the brewing of barley. While fermented beers, meads, and wines were known throughout northern Europe, distillation is an entirely different technology and constituted a historic technological achievement.

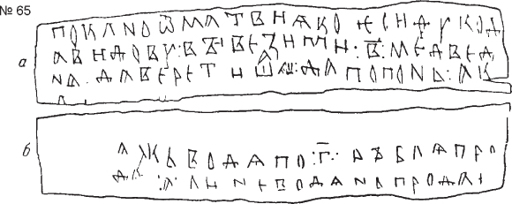

It is tricky to interpret these documents, since they are not in Russian but, rather, an Ancient Novgorodian dialect of early Slavic and Finnish/Karelian languages. That issue notwithstanding, historian A. P. Smirnov (no relation to the vodka of the same name), focused particular attention on birchbark document no. 65, which clearly includes the letters that spell the word , pronounced

, pronounced

vodja

.

Linguists agree that the word

vodka

is the diminutive form of the Slavic word for water:

voda

. Certainly

vodja

sounds a lot like the Russians’ dear “little water,”

vodka

. Since letter no. 65 dates from the mid-thirteenth century, therefore—according to Smirnov—this supposedly “most important document in the history of the production of vodka” dates its birth to 1250.

31

If this sounds like an even bigger stretch than Pokhlebkin’s fabrication, that’s because it is. First of all, Russian archaeologists determined that the stratum in which this document was found dates from the early fourteenth century at the earliest. Besides, any archeologist knows that fieldwork is never so precise as to pin down any specific year. As with Pokhlebkin, these scientists’ claims are far more precise than the evidence warrants. Second, Smirnov does not explain how or from whom the early Novgorodans learned the science of distillation, since 1250 predates the technique’s arrival even in Europe.

N

OVGOROD

B

IRCHBARK

D

OCUMENT

N

O

. 3,

CIRCA

1360–1380

C.E.

Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

?

N

OVGOROD

B

IRCHBARK

D

OCUMENT

N

O

. 3,

CIRCA

1360–1380

C.E.

Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

?

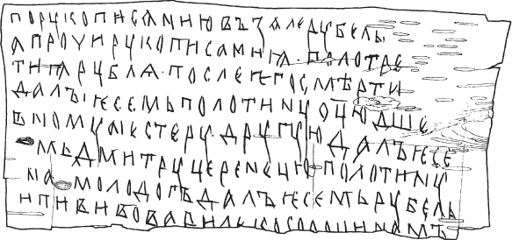

N

OVGOROD

B

IRCHBARK

D

OCUMENT

N

O

. 689,

CIRCA

1360–1380

C.E.

(

PART A

). Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

?

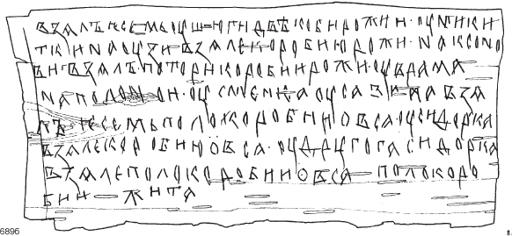

N

OVGOROD

B

IRCHBARK

D

OCUMENT

N

O

. 689,

CIRCA

1360–1380

C.E.

(

PART B

). Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

?

N

OVGOROD

B

IRCHBARK

D

OCUMENT

N

O

. 65,

CIRCA

1300–1320

C.E

. The letters spelling can twice be seen in the bottom section, no. 65 b. Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

can twice be seen in the bottom section, no. 65 b. Source: Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

Birchbark Literacy from Medieval Rus,

http://gramoty.ru/index.php

?