Untold Stories (64 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

In much the same category as the Lucas van Leyden, a painting I find ravishing but can't find much to say about is John Sell Cotman's

Greta

Bridge

, a watercolour in the British Museum. I was brought up on Cot

man, in that they have a very good collection of his work in Leeds, most of it bequeathed by Sidney Kitson, who was so fond of the artist he was said to suffer from Cotmania. Understandably in my view, as I've yet to see a Cotman I didn't like. But that just about says it all. It's true one could find things to say about Greta Bridge itself, which has a dramatic history, and when I was a boy was the subject of a

Children's Hour

serial. But nothing I could say would add much to the appeal of the painting, and if there is nothing to be said one should have the sense not to say it.

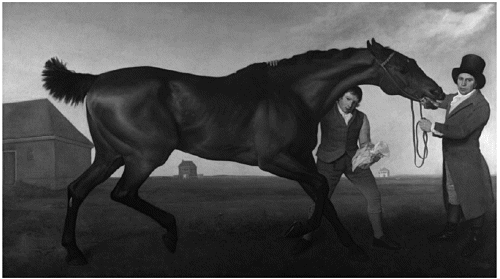

My second choice,

Hambletonian, Rubbing Down

, by George Stubbs, was painted in 1800. It hangs at Mount Stewart, a National Trust property in Northern Ireland. Hambletonian was one of a string of racehorses belonging to Sir Henry Vane Tempest, a landowner from County Durham. Having already won some important races, the horse was matched at Newmarket in 1799 against a much-fancied rival, Diamond. The race was exceptionally dramatic, both horses being cruelly whipped and goaded with the spur until, utterly exhausted, Hambletonian managed to pull ahead and win the race by half a neck. Though he went on to win other races, the horse never wholly recovered from his ordeal and was eventually retired to Wynyard Park in County Durham, where he is buried under a large oak tree.

George Stubbs,

Hambletonian, Rubbing Down

Stubbs was an old man of seventy-five when he painted

Hambletonian

, one of his last pictures, but the drawings he made of the skeletons and muscles of horses years before show that he knew horses literally inside out. For a long time this didn't help his reputation, as he was thought of as just an animal painter. It's only in the last thirty years that he has come to be recognised as one of the greatest English painters, a landmark in this process the exhibition at the Tate in 1985, curated by Judy Egerton, from whose magnificent catalogue I'm cribbing most of what I am saying.

The background of Stubbs's painting hints at the scene of Hambletonian's triumph, as we can see the pavilions and the winning post of the course over which his famous race was run. There's no sign of the piteous state the horse must have been in at the conclusion of the race, no weals from the whip or blood from the spurs. Nor do the groom and boy who have charge of the horse show any emotions. It's obviously not âThe Triumph of Hambletonian', which may well have been the kind of painting the owner wanted. Certainly Stubbs had a great deal of trouble getting paid for his commission.

Both groom and boy look quite stern and self-possessed, and though both are the owner's servants they seem anything but servile, and are so indifferent to our regard as to appear almost arrogant. The reason may be that they have a skill that we do not share. They know about horses and this horse in particular, and they look down on us, who are watching them, because we don't. Groundsmen and coaches have a similar attitude to spectators: they are professionals â we are just fans.

I can't decide whether Stubbs has made the boy's right arm longer than it could possibly have been in order to have it reach over the horse's neck. One would like to see a reverse angle on the scene in order to be sure. Mind you, I'm no authority. As a boy I was hopeless at drawing horses and thought there was something almost magical about other children who could. There were more horses about then, of course (though not like Hambletonian). Coal was delivered by horse and cart, as was milk, and when I was evacuated during the war â though I find this hard to believe

now â I went to Ripon market by horse and cart. On the other hand, I have never been to a horse race.

Stubbs was born and brought up in Liverpool, then moved to York, and then beyond York to an area even more remote than the one inhabited by his contemporary, the clergyman Sydney Smith, who complained that he was so remote from civilisation he was twenty miles from a lemon. An absence of lemons wouldn't have bothered Stubbs, who shut himself up in a farmhouse at Hawkstow in north Lincolnshire, in what's now Humberside, where he dissected and drew the corpses of horses, only abandoning the cadaver when it stank so much as to be intolerable.

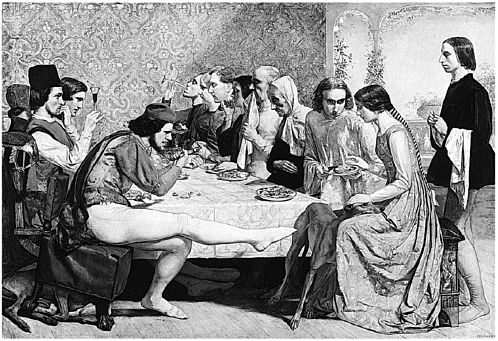

My third choice is

Lorenzo and Isabella

by Sir John Millais, painted in 1849 and now in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Millais's picture was inspired by Keats's âIsabella; or, The Pot of Basil', a story retold from Boccaccio. Lorenzo is in love with his master's daughter, Isabella, and this arouses the resentment of her three brothers, who lure him into the forest and murder him, leaving Isabella to think that he has abandoned her. Lorenzo then appears to Isabella in a dream and reveals the whereabouts of his forest grave: she digs him up and brings home his head, which she keeps in a pot on her window sill in which she grows herbs.

It's a macabre tale which, in Millais's painting, is just beginning, Lorenzo handing Isabella half an orange while the brothers look on. The most brutish brother teases his sister's dog with his foot, while the eldest brother looks as if he is already making plans to do away with the upstart. On the window sill a pot of herbs hints at the story's dreadful conclusion. Most of the people in the painting, even the unsympathetic brothers, are portraits of Millais's friends and family; for instance, the old man delicately touching his napkin to his lips (in a gesture I had hitherto associated with northern ladies in teashops) is a portrait of Millais' father.

Many Pre-Raphaelite paintings, this one included, I find to some degree sinister or disturbing, peopled with characters who seem fearful or haunted, like the flower-seller in Ford Madox Brown's

Work

or the potboy in the same picture, or the young John the Baptist in Millais's

Christ in the

Carpenter's

Shop

. They all look as if something dreadful is about to happen, which in Lorenzo's case is no less than the truth.

On one side of the table are the brothers, three in Boccaccio, two in Keats and it could be two or three in Millais â the young man at the rear looks less evil-minded than the other two. It's a deliberate configuration and confrontation, but slightly awkward, as the rest of the party have to budge up on the other side of the table â though their sober dress suggests they are all inferior members of the household anyway and so not entitled to much comfort. The dogs, incidentally, don't do at all well here, one getting teased by the probing foot, the other quite likely to have its paw or tail crushed when the awful brother puts his chair back.

John Everett Millais,

Lorenzo and Isabella

I suppose the brothers would defend themselves by saying that they are concerned for their sister's virtue but I don't believe it, the young men's obligation to keep their sister pure having more to do with their own frustrated desires than with any concern for morality. Besides, they don't want her marrying Lorenzo because, however capable he might be, her

destiny is to marry into the aristocracy, thus improving the family's status. This element â and the mercantile activities of the family â is stressed by Keats, and Millais was very much aware of it.

The painting had originated as one of a series of etchings planned by Millais and Holman Hunt in the first flush of Pre-Raphaelite enthusiasm and there is a drawing by Holman Hunt,

Lorenzo at Work Supervising the

Brothers' Warehouse

, which strikes the same note. The initials of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, incidentally, are visible on Isabella's stool. Millais was not yet twenty when he painted the picture and its technical accomplishment is astonishing, Ford Madox Brown saying that the modelling of the napkin carried by the servant was the painting's supreme achievement.

It was exhibited at the Academy in May 1849 and sold for

£

150 to three tailors in Bond Street who were making a start in picture-dealing. The tailors beat Millais down from his original price but threw in a suit of clothes as compensation. People disliked the painting so much, however, that they got rid of it for the

£

150 they had paid and lost the suit of clothes into the bargain. It passed through one or two pairs of hands before coming to the Walker Art Gallery as early as 1884.

What always makes me remember the painting is the bully's wonderful, terrible leg, arrogant, perfectly proportioned and up to no good. Here teasing the greyhound, today it might be flung loutishly across the aisle of a bus or shoved on a spare seat in the train, a hurdle one has to take (stepping over it or asking for it to be removed) if one is to retain one's self-esteem.

It's the leg of a ballet dancer â Nureyev's leg, if you like. I only saw Nureyev dance once, in

Manon

at Covent Garden. He was partnered by Anthony Dowell, who is much more delicately made. There was nothing delicate about Nureyev. He had legs, like the leg in the painting, that were not so much legs as hindquarters. Nureyev was often compared to Nijinsky and the comparison is apt. He was like Nijinsky, but it was Nijinsky the horse.

The last of my four paintings comes from the art gallery at Aberdeen,

which has a particularly good collection of modern British paintings, and from which I was hoping to choose Eric Ravilious's

Train Landscape

. It's a painting redolent of all the journeys by train that I remember, particularly in my teens and during my National Service, when it was still possible to explore the English countryside by rail, a period that the foolishness of Dr Beeching put an end to. I then found that I'd been forestalled and that this particular Ravilious had already figured in Sainsbury's Pictures for Schools. Aberdeen has others, though, and appropriately, as so much of Ravilious's work was done in the north of Scotland. He was a war artist and painted the convoys waiting in Scapa Flow to depart on the gruelling voyage to Murmansk. It was on one such trip that Ravilious himself died, killed off Iceland in 1942.

Two other paintings of his that I like very much are

Farmhouse Bedroom

(1939), which is in the V&A, and one of England before the war called

Tea

at Furlongs

. It's seemingly a very peaceful scene but its emptiness is ominous and I think it could equally be called âMunich, 1938'. I might well have chosen it but it turns out to be in a private collection and so doesn't qualify.

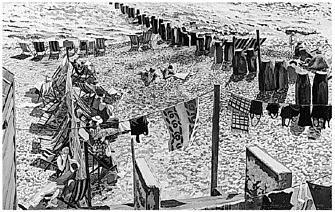

Stanley Spencer,

Southwold 1937

I ended up plumping for another of Aberdeen's pictures, a beach scene by Stanley Spencer,

Southwold

1937

. In my childhood, holidays at the seaside were often quite doleful affairs. It rained or was cold and if we weren't cringing in the shelter of some breakwater, as they're doing in the

picture, we were probably trailing up and down the seafront until we were allowed to go back to the boarding house (which was strictly off-limits between meals). That was Morecambe or Cleveleys on the north-west coast, whereas this is Southwold in Suffolk, but the sea looks much the same. Stanley Spencer described it as âdirty washing water colour ⦠splashed by homely aunties' legs' and the air of Southwold as âfull of suburban seaside abandonment'. He's right about the sea, though Southwold looks more sedate than he describes, no aunties paddling at the moment and scarcely a child that I can see. It's certainly not Blackpool.