Untold Stories (81 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

The dietary precautions I took were of the simplest, avoiding red meat, eating a good deal of broccoli (which I don't care for), taking a vitamin supplement and also drinking green tea, the beneficial properties of which seem to me well-authenticated.

These apart, I tended to steer clear of cancer, seldom reading about it in the papers, their coverage of the subject almost carcinogenic in itself,

forever hunting after drama or pathos, and garbling what few certainties there are and, it seemed to me, altogether relishing a subject which (like the deaths of children) is always a good column filler.

This fastidiousness might, of course, be one of the reasons I got cancer in the first place. There is a notion, canvassed by no less an authority than the poet Auden, that cancer is almost a product of reticence, or at least of being buttoned up, a disease less likely, therefore, to affect the busy, the brash or the outspoken.

It's the kind of reach-me-down psychology you find nowadays on daytime TV, where, if reserve is indeed carcinogenic, the audience must be largely immune. Seemingly handpicked for their coarseness and social inadequacy, these vociferous assemblies take readily to the notion that restraint is uncalled for, and indeed perilous to psychic health. In this age of glandular freedom, the adrenalin must flow untrammelled as even manners carry a risk, to all the other drawbacks of shyness now added that of malignant disease.

Early in 2000 I had to go up to St Catherine's College at Oxford to take part in a discussion and question-and-answer session with Nicholas Hytner, who was at that time Cameron Mackintosh Professor of Theatre Studies. The Senior Tutor of St Catherine's was Michael Gearin-Tosh, who, five years or so before, had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma and given six months to live.

With some courage, it seemed to me (and with a certain relish for the dramatic), Gearin-Tosh had rejected the few conventional treatments that were on offer at this late stage of the disease, particularly the gruelling chemotherapy that offered the only hope. Instead, after reading all the literature to do with his condition (which in itself takes a good deal of nerve) and with the help of medical colleagues and the goodwill of his college, he embarked on a course of treatment virtually of his own devising.

*

This was a regime of some rigour and expense which Gearin-Tosh has himself described, the efficacy of which, certainly to begin with, must

have seemed an almost lunatic act of faith, and with all the hallmarks of a crank. There was a daily regime of two caffeine enemas; every morsel of food had to be organic and, even so, all fruit and vegetables needed to be washed with Malvern water. This obsessive hygiene calls up thoughts of Howard Hughes. When I met him in February 2000 at sherry in the college common room, always on the edge of the conversation hovered a young man with a jug of carrot juice, a beaker of which Gearin-Tosh sucked through a straw, the straw, like Coward's cigarette-holder, a punctuation for his wit.

Tall and not undemonstrative, and with a swooping voice, and hands clasped high on his chest, Gearin-Tosh was an exotic figure, Lytton Strachey without the beard, but what was astonishing about him was that against all the odds he was alive at all. He is not cured but he has survived ten years since the original diagnosis and, carrot juice always at his elbow, still survives, very much in the pink and always in exuberant spirits.

Had we not to some extent both been in the same boat, I might have regarded this extravagant figure, and the ambient carrot juice, as almost a joke, and someone to be remembered and maybe written about. As it was, I tried to glean what tips I could, both of us, I suspect, recognising straight away that I was never going to be able to run to the whole package, âDon't eat salt' the only one of his injunctions I now remember, as he explained the part salt played in the mechanism of cancerous cells.

After Nicholas Hytner's lecture I didn't stay for dinner in hall, though I would have been interested to see more instances of Gearin-Tosh's diet, and how it compared with the more Lucullan regime of the other dons. Perhaps the spectacle of Gearin-Tosh's extraordinary survival and his unending struggle ought to have cheered me, but I came away from Oxford that night naggingly depressed. I did not know if, all things considered, such a rigorous regime would work for me (though nor did Gearin-Tosh until he'd tried it). Besides, all things hadn't been considered. I hadn't gone into the nature of my condition as Gearin-Tosh had; I hadn't weighed up the pros and cons. I knew that I didn't want the treatment to become my life and who was to say that all the painstaking effort

notwithstanding this exotic treatment might not be a gamble that would work for him but not for me? What I did know was that I was too disorganised, too all over the place, even to give it a try. Had I been Gearin-Tosh, to do all the preliminary reading and investigation that his diet required would have taken me all the six months that were supposedly left to him. How could I employ somebody to ply me with carrot juice or swill every bit of produce I ate with Malvern Water? And who, I thought irreverently, swilled the Malvern water?

No, his was an epic struggle and, as Lindsay Anderson told me many times, I was not suited to epic. I could say that this was being a fatalist and that I was just hoping to muddle through. More truthfully, I was lazy and my laziness persisted even into the grave. It was indolence unto death.

In this, though, I suspect I resemble the general run of humanity more than I like to think. With cancer, submission to the disease and deference to the doctors is the usual form, perhaps because the patient is in the presence of a mystery. Or two mysteries ⦠the condition itself and the death it so often entails. Nothing that the patient can do about it, one would like to think. Wait and see the order of the day.

Back in the endoscopy unit, there have, thankfully, been no surprises.

âI'm coming out now,' says the doctor. âAll well.' I open my eyes and venture to watch on the screen the last leg of the camera's journey down my gut, which looks like a tunnel out of Disney. We pause for a reverent moment to gaze at the titanium clip which marks the spot where, five years ago, Mr Northover snipped out the offending section of my bowel, and neatly joined the ends together, the clip looking not unlike a coffee bean.

Wheeled back to my cubicle, I lie for half an hour or so, recovering from (and actually still enjoying) the effects of the Valium; then I get up, pay my bill at the desk and come home. It's another of those small reprieves which have marked out the last five years, more momentous than the others, perhaps, in that it is five years, but the habit (and the precaution) of treating whatever happens as provisional is hard to lose. So, though I'm cheerful, I don't rejoice or dare to think I'm cured â though

in statistical terms, five years without a recurrence would qualify. Actually I daren't think that lest I activate the laws of irony and the opposite happens.

Having been given the all-clear I pay my routine visit to my surgeon, who now feels able to tell me that he had put the odds against my survival much higher than he had ever dared reveal. Having told me they were fifty-fifty the truth, apparently, was nearer one in five.

So far from feeling encouraged or even triumphant at this news I had a difficult few days, wondering now whether I was truly as well as I felt and why it was that I'd been singled out for survival.

In time these misgivings subsided, leaving me with a feeling to which I can honestly attest, though it's both surprising and slightly ridiculous, and that is pride. It's surprising because pride is normally something I'd shy away from and it's ridiculous because that I have survived â or survived so far â is entirely without merit on my own part. The credit lies with John Northover and Maurice Slevin, who treated me, and with my GP Roy Macgregor who had helped me at every stage of the journey; and of course my partner Rupert Thomas. If my own frame of mind has contributed to my recovery, that never cost me much conscious effort and was as much thanks to them as to any determination on my part.

And yet, more than in anything that I have written or otherwise achieved in my life, against all sense and logic, I feel pride in having come through, or come this far. Unlike so many others, much worse afflicted, I did not even have to fight. Yet I am thereby enrolled as a member, I hope a long-term member, of the exclusive aristocracy of those who have survived cancer.

Thankfully, it's a growing aristocracy, and one day, I'm sure, such survival will seem commonplace and hardly worth mentioning. Meanwhile, I am one of many who are here when they did not expect to be here. Take heart.

*

No one has ever satisfactorily explained to me how, short of frequent colonoscopy, a physician sorts out benign bleeding from piles from a more sinister cause. And if it puzzles me, who has been through the process, I imagine it must puzzle other patients in the same predicament.

*

See âA Common Assault', p. 557.

*

Living Proof

, Michael Gearin-Tosh, Scribner, 2001.

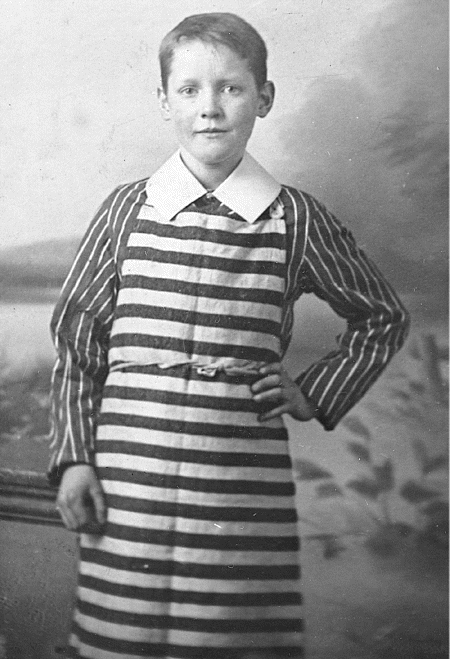

1 My father, aged twelve

2 St Bartholomew's Church, Armley

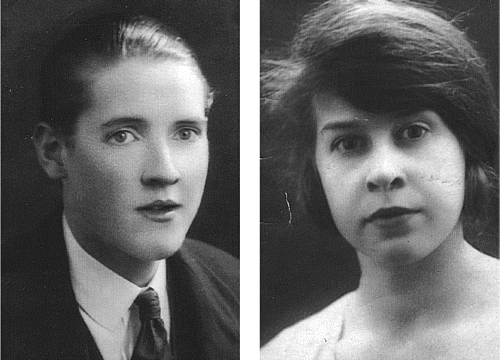

3 & 4 My parents, shortly before they were married

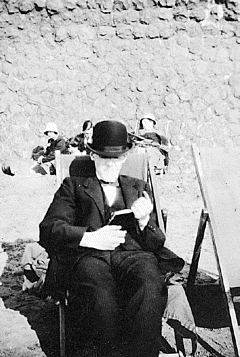

5 Grandma Peel

6 Grandad Peel

7 Dad, on holiday as a young man

8 Mam and Gordon with Aunty Kathleen