The Oxford History of the Biblical World (36 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Saul’s years of leadership did little to centralize power in one place or in one family. While Saul’s family continued to have claims to the throne after David became a contender, it was still conceivable that someone outside his family (albeit a son-in-law) could rule instead of a male in the direct line from Saul (Ishbosheth, for instance, as in 2 Sam. 2.8-11). David’s personal retinue is not only kin-based, but includes people who are loyal to David as an individual; they are also dependent on his leadership and the redistribution of booty that he provides (1 Sam. 22.1-2; 30). Again, a competition for David’s throne breaks out among his sons, as though the principle was now established for the crown to pass to a son—but not yet any tradition backed by the rule of law that would designate precisely which son, so that the centralization and permanence of the position would be accomplished. This step is not completed until Solomon is appointed (1 Kings 1-2). Already during David’s reign, or chiefship, a professional bureaucracy had grown up (2 Sam. 8.15-18; 20.23-26), a sign of a centralized monarchy. By Solomon’s reign, the government is established in Jerusalem; a palace and a central temple are to be built; and the chiefs occupations have become more specialized than in the time of Saul and David, both of whom performed religious functions as well as assuming political and military leadership.

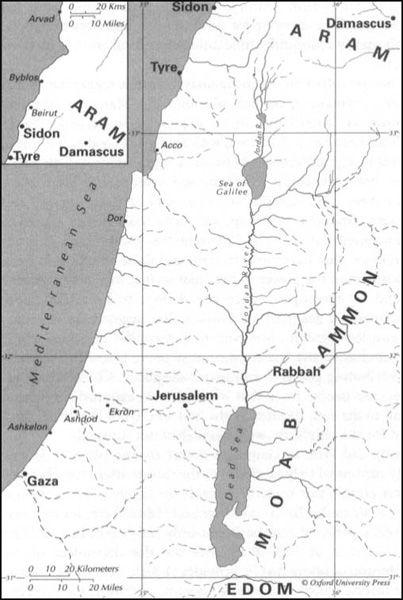

Iron Age Israel did not take shape in a vacuum. The Philistines and Phoenicians on the coast and the Transjordanian peoples to the east frequently appear in biblical sources, and so an understanding of these cultures contributes to a more complete picture of the period of the judges. The Philistines, Israel’s southern coastal neighbors, have received particularly intense scholarly scrutiny, and recent excavations at ancient Philistine cities have greatly increased our knowledge of them.

Major Philistine and Phoenician Cities in the Early Iron Age

Uprooted by the fall of the Mycenaean civilization in the Aegean at the end of the Late Bronze Age, the Philistines are one part of the group called “Sea Peoples” by the Egyptians. An earlier contingent of Sea Peoples fought the Egyptians under Pharaoh Merneptah in the late thirteenth century

BCE

, but Egyptian records do not list the Philistines among them. In inscriptions from the time of Rameses III (1184-1153

BCE

), however, describing his victory over groups of Sea Peoples, the Philistines are listed, along with the Tjeker (or Sikils—compare “Sicily”), the Denyen, the Sherden (“Sardinia”), the Shekelesh, and the Weshesh. Other Egyptian sources inform us that the Sikils eventually settled in and around the coastal town of Dor, and the Sherden

probably north of them, around Acco, while the Philistines occupied the southern coast about 1190. Philistine settlement is determined by the appearance of Mycenaean IIIC (monochrome) ware, in levels immediately above the earlier Mycenaean IIIB (imported) pottery and immediately below the later, locally made “Philistine” bichrome ware. Both the monochrome and the bichrome pottery (so named because they are decorated with one or two colors of paint, respectively) were made locally in Canaan, as we know from tests on the clays used, but they have Aegean antecedents in motifs and design.

The Sea Peoples destroyed many sites in their migrations—on Cyprus, in Anatolia, and along the Levantine coast, including the Syrian city of Ugarit and its port at Ras Ibn Hani—but they were defeated by Rameses Ill’s troops about 1175

BCE

in a land and sea battle. The Philistines remained in the area of southern Canaan where they had already established themselves, centered on a pentapolis (Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, Gath, and Gaza) headed by five what the Bible calls

seranim,

“lords” (a word perhaps related to Greek

tyrannos).

From there they prospered and grew, until by the second half of the eleventh century they had become a threat to their eastern neighbors, the Israelites.

The only Philistine temples so far excavated have been three phases found at Tell Qasile, on the outskirts of modern Tel Aviv. There is evidence of sacrifices, and in one phase a small, auxiliary temple accompanied the main temple (presumably for a consort or a secondary god), a feature typical of Aegean but not Canaanite temples. Many Philistine religious objects have been found, including a seated goddess with elongated neck, a piece with Mycenaean precedents; several zoomorphic vessels; and fragments of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic masks, presumably worn in rituals. A few Philistine seals from this period have also been found, with animal and human figures, such as the lyre-player from Ashdod, and some with writing that resembles the undeciphered Cypro-Minoan Late Bronze Age script.

Although we know less about the Transjordanian peoples in the early Iron Age than we do about the Philistines, we can still sketch the outlines of settlement there. The material culture of Iron Age I in the areas of Edom, Moab, Ammon, and the southern Jordan Valley was like that on the west side of the Jordan River: small settlements growing in number throughout the period. Despite biblical references to kingdoms in Edom, Moab, and Ammon, archaeological evidence suggests that these descriptions are anachronistic. These areas were settled during Israel’s early emergence, but we do not find any sophisticated level of social and political organization in the early Iron Age in Transjordan. The northern Jordan Valley even shows evidence, in the later part of the period, of Philistine or Sea People incursion, probably through the Jezreel Valley.

Later inscriptions show that Ammonite, Moabite, and Edomite are all Canaanite languages, related to Hebrew and Phoenician. The evidence of material culture and of inscriptions, then, ties together the peoples east and west of the Jordan River in the period of the judges and later. Even in the immediately preceding Late Bronze Age, the archaeological evidence for northern Transjordan is much the same as that for Palestine to the west. The Late Bronze period saw a series of major cities on both sides of the Jordan River, with evidence of international trade. Southern Transjordan, however, presents a different picture, with sparse settlement. The question arises, as

it does to the west of the Jordan, just where the people came from who make up the Iron Age Transjordanian entities. Were they part of the same movement that saw the highlands of Israel settled? Or did they move in from the north and the south to settle what later became Ammon, Moab, and Edom? Their languages and material culture suggest that at least some portions of the later kingdoms were closely related to their western neighbors, but beyond that we cannot go.

While Genesis 19.30-38 pairs Moabites and Ammonites as the descendants of the incestuous union of Lot and his two daughters (see also Deut. 23.3-6), the Bible elsewhere makes a distinction between the Ammonites on the one hand and the Moabites, Edomites, and other Transjordanian peoples on the other. According to the narrative in the book of Numbers, the Edomites, Moabites, and several Amorite groups had already established kingships by the time the Israelites come into contact with them. While the Israelites are wandering in Transjordan, before their entry into the land, they are confronted with a king of Edom who refuses them passage through his territory (Num. 20.14-21; see also Deut. 2.4-8) and with Balak, king of Moab, in the Balaam stories (Num. 22-24), plus the Amorite kings Sihon and Og (Num. 21.21-26, 33-35; Deut. 2.26-3.7) and an even earlier unnamed Moabite king mentioned in the Sihon story (Num. 21.26). The Ammonites, however, while said to have a strong boundary (Num. 21.25), are not described as a kingdom until Judges 11.12, in a passage that reprises the stories of Israel’s way around Edom and Moab on their way to the land (see Num. 33.37-49). The narrative of the negotiation between Jephthah and the Ammonite king (Judg. 11.12-28) is confused, however, since it mentions Chemosh as the god of the people Jephthah was negotiating with, and Chemosh is the god of the Moabites, not the Ammonites. So even this mention of an Ammonite king may be a mistake or a confusion in the text.

The biblical narrative in Numbers and Judges, then, suggests that the Ammonites were not organized into a kingdom as early as the Moabites, Edomites, and Amorites of Transjordan. But archaeological evidence shows that the portions of these narratives seeming to indicate early political sophistication among the Transjordanian peoples are actually anachronistic and cannot be relied on to describe early Iron Age Transjordan. One of the oldest passages in the Bible also implies that that region was not organized into kingdoms. In Exodus 15.15 the tribal chiefs of Edom and the leaders of Moab are distressed when they hear about the approach of the Israelites. In this older description of Israel’s meeting with Edom and Moab during their wanderings, we find not kings of Edom and Moab, but instead leaders with less sophisticated titles.

We know even less about the Phoenician cities in this period. Tyre, Sidon, Arvad, and Byblos are all mentioned in the fourteenth-century

BCE

Amarna letters found in Egypt, and none is completely independent of the great powers, especially Egypt, at that time. For the early Iron Age we have few written sources and none from the Phoenician cities themselves. Around 1100 the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser I, on an expedition to procure cedar wood, claims to have exacted tribute from Sidon, Byblos, and Arvad. The eleventh-century Egyptian tale of Wen-Amun shows their independence from Egypt, since it involves an Egyptian envoy who was treated badly in Byblos while he too was on a journey to obtain cedar. The cities appear to have operated independently of each other, as well. There was no “Phoenicia,” if by that we mean

a unified state of any kind; there were only Phoenician cities and their spheres of influence.

That both the Homeric epics and the Bible refer to Phoenicians as “Sidonians” indicates that Sidon was the major city during the period of the judges. Sidon itself, as well as Arvad and possibly Tyre, was destroyed by the Sea Peoples in the early twelfth century

BCE

, but all were rebuilt. By the end of the Iron I period, Tyre was competing with Sidon for ascendancy as the most important of the Phoenician cities, and had an established monarchy. Epigraphic finds in Crete and Sardinia place Phoenicians there by the eleventh century, probably as merchant sailors. There is still no evidence of formal Phoenician colonization in the Mediterranean, however, before the ninth century.

More is known about Byblos and Tyre starting around 1000

BCE

. From Byblos a series of tenth-century royal inscriptions gives us at least the names of the kings and shows us that the Byblian language and script are slightly different from those from other Phoenician sites. What we know of Tyre’s rulers comes from the Tyrian annals reported by the first-century CE historian Josephus, supported in part by the ninth-century Nora inscription from Sardinia mentioning the Tyrian king Pummay (=Pu’myatan=Pygmalion).

Among the most exciting archaeological finds are ancient inscriptions. For some eras, writings uncovered by excavation have filled out an otherwise sketchy political and social picture of the ancient world. Unfortunately, the era of the judges has not yet produced such abundant information. But while no inscriptions of any appreciable length have yet been recovered from the Iron I period in Syria-Palestine, several short inscriptions have appeared, giving the names of many ancient individuals and the occupations of some, and shedding light on the impact of a simple writing system on the lives of all sorts of people. The inscriptions from this period are incised or inked in one form or another of the linear alphabet, the forerunner to our own alphabet. This alphabet had been invented around 1500

BCE

and by the early Iron Age was in widespread use. The largest number of inscriptions from this period are a group of bronze arrowheads from Lebanon and Israel inscribed with personal names, identifying the arrow’s owner and often his father or master. We do not know why people inscribed their names on arrowheads—whether to make them easier to retrieve, or for divination, or simply for decoration of an arrowhead or javelin head that would never actually be used.

Most of the rest of the early Iron Age inscriptions are a mixed lot of potsherds, usually with only two or three letters inscribed, but sometimes with personal names; and seals, usually including a personal name. One exception is a twelfth-century

BCE

ostracon that includes an abecedary, found at Izbet Sartah east of Tel Aviv. An abecedary is an ordered listing of the letters of the alphabet, and several such inscriptions have been found in the Levant, including some from ancient Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra) on the coast of Syria, where the writing system was alphabetic cuneiform. The Izbet Sartah ostracon is crudely written, and the abecedary includes a number of mistakes; the first four lines of the ostracon seem to be a nonsense stream of letters, and the ostracon may be an exercise done by someone still learning to write.