The Oxford History of the Biblical World (77 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

It is impossible to determine what percentage of Jerusalem’s population actively supported such efforts. Beyond the high priest and his associates, that number may have been small. It is also difficult to know how many actively opposed Antiochus’s decrees. For many of those who did, the initial action was to abandon Jerusalem for the countryside. Most of the populace probably did nothing, the demands of family and business dictating a policy of noninvolvement. When active resistance arose, it originated in the small towns of Judea, not in Jerusalem. This was the Maccabean revolt. Its beginnings, initial successes, and varied results constitute major elements in the final century of the Hellenistic period in Judea. But before turning to these events, let us consider the enigma that is Antiochus IV.

What was anomalous about Antiochus IV’s activities was his determined effort to wipe out a religion. By and large, ancient polytheists were tolerant of the beliefs and practices of other peoples. In a world populated by a large number of divine beings, there was no sense that any of them needed to be forcibly eliminated. Deities might show themselves to be weak, ineffectual, fickle, unpredictable, or otherwise problematic. In such cases, adherents might choose to cease worshiping specific gods or alternatively to show their devotion in different ways. The only precedent to Antiochus’s actions is found more than a thousand years earlier in Egypt, when Pharaoh Akhenaten attempted to eliminate all gods except the Aten (the solar disk)—and, of course, himself. But Akhenaten’s unsuccessful example, even if known to Antiochus IV, could hardly have constituted the major impulse that drove him.

The classic scholarly explanation seeks the primary impetus in Antiochus’s desire to promote a pan-Hellenistic culture, including religion, that would harmoniously unite all of his subjects under one banner. It is argued that Antiochus saw himself as a veritable incarnation of Zeus, especially Olympian Zeus. This would explain his order to turn the Jerusalem Temple into a center for the worship of Zeus Olympius and would clarify his epithet,

Epiphanes,

or “God-manifest.” But the evidence indicates that such long-range, long-term goals far exceeded whatever Antiochus had in mind. At the other extreme is the idea that Antiochus had nothing in mind, that in fact he was out of his mind, driven by delusions or caught up in the eccentricities of an unstable personality. Many stories that circulated about Antiochus pointed up

odd features in his personality and his actions. Not without cause did punning satirists of the day change the solemn epithet

Epiphanes

into

Epimanes,

meaning “madman.” But such an appeal to the irrational is also at odds with the recorded facts of Antiochus’s reign. After all, this Seleucid monarch could claim many accomplishments, and his assault on the Jewish religion was not capricious or mindless.

Other explanations attribute Antiochus’s actions primarily to interest in money or in politics. According to one, Seleucid financial obligations had all but bankrupted the empire, and Antiochus needed to get additional funding in any way possible. But in fact Antiochus’s circumstances were not so dire as commonly portrayed, and even if they were, an attack on the Jewish religion seems an odd and ineffectual way to achieve solvency. Antiochus’s interest in political stability may have led him to support Menelaus at all costs and against all enemies. But if that were the primary goal of Seleucid policy toward the Jews, less provocative means could have been devised to achieve it.

Perhaps Antiochus had learned the value of suppressing potentially rebellious religious cults during his stay at Rome. In 186

BCE

, while he was there, the Roman senate had attempted to suppress the worship of Dionysus/Bacchus on the grounds that its reportedly orgiastic excesses and foreign practices posed a threat to the stability of the self-consciously sober society of the day. This incident, however, is a dubious parallel to Antiochus’s more far-reaching efforts to uproot the Jewish religion from its native soil. Or it could be that Antiochus was primarily motivated by a desire to erase the stigma attached to him and his reign by his utterly humiliating defeat by the Romans in Egypt. Other subject peoples might exploit this apparent weakness unless he showed, dramatically and decisively, that he was in charge. His decrees and subsequent actions against the Jews were no doubt dramatic, but it is difficult to ascribe their primary motivation to the realm of public relations. In short, there is no evidence that he planned to use the Jews as an example in this way.

Still another view is to place the burden not on Antiochus but on Jewish leaders, especially Jason, Menelaus, and their supporters. They are to be seen as the primary instigators in the efforts to hellenize Jerusalem and its rituals, and they are the ones who counseled Antiochus to adopt increasingly extreme policies in this regard. But again, the evidence does not support the view of Hellenism and Judaism as mutually exclusive allegiances or that their supposed opposition fueled the internal strife in Jerusalem, at least prior to 167

BCE

. Nor can it be demonstrated that a Seleucid ruler during this period took his marching orders from the very people he ruled, even if their leaders had aligned themselves with him.

In short, we have no single answer to the question of what motivated Antiochus IV to promulgate and enforce the decrees of 167. More likely the solution lies in a combination of all these suggested factors. Brilliant but inconsistent, methodical yet brash, generous and cruel, Antiochus was a complex individual living in dangerous times. History would have been very different had he followed his loftier instincts.

As we have seen, the majority of Jerusalem’s population silently acquiesced to even the harshest of Antiochus IV’s decrees. In addition to the understandable desire to survive, there was a widespread belief that rebellion against a king, even a harsh

foreign king, was against God’s will. The biblical text records numerous instances of Israel’s refusal to recognize that the Assyrians, Babylonians, and other powerful foes were in reality the rods of divine anger, to punish them for their sins. Perhaps the same was also true of the Seleucids.

But when had an enemy struck at the very heart of Israel’s monotheistic faith? What would the heroes of old have done in such a circumstance? Would they have quietly accepted Antiochus’s actions as the result of divine inevitability? Would they have simply abandoned Jerusalem for the relative security of the countryside? At least one family found inspiration for active opposition through their interpretation of the biblical record. In the town of Modein, not far from Jerusalem, lived the priest Mattathias and his five sons. One of his ancestors had been named Hashmonay, the origin of the collective designation of Mattathias and his descendants as the Hasmoneans. Around this family gathered a small band who initiated their armed conflict with the Seleucids through a series of guerrilla raids. Since they were vastly outnumbered and had only limited support from their fellow Jews, confining themselves to guerrilla operations was wise. In addition, the Hasmoneans could take advantage of their superior knowledge of the area’s topography. After the death of Mattathias, who was elderly when the conflict began, his son Judah (Judas), also known as the Maccabee (Maccabeus; the name means “hammer”), assumed the leadership and continued the series of military successes that the Hasmoneans had enjoyed almost from the beginning.

At first, Seleucid officials did not take seriously the threat posed by Judah. But his string of victories brought him increasing fame and increasing numbers of soldiers. Syria’s leaders could no longer afford to ignore them, especially because of Judea’s strategic location near the northern border of the weakened but still dangerous Ptolemaic empire. More substantial armies, commanded by experienced generals, were sent against the Maccabees, but the results were the same: Jewish victory, Seleucid defeat. As the situation grew graver, it attracted the personal attention of Lysias, whom Antiochus IV had placed in charge of the western portions of his kingdom while he himself headed east. Lysias marched at the head of a massive army, but could do no better than fight to a draw against Judah’s outnumbered but energized troops.

In early 164

BCE

negotiations opened between the Seleucids and the Jews. The Seleucid offer extended the promise of amnesty to all who renounced their rebellious activities and returned to their pre-rebellion lifestyle. Henceforth Jews could once again carry out the commands of the Torah, but they could not punish those Jews who chose not to. Moreover, the Jerusalem Temple remained in Seleucid hands, effectively barring the Jews from practicing the system of sacrifices that was central to communal worship. Equally upsetting to many was Menelaus’s confirmation as high priest. Nonetheless, this “Peace of Lysias” was accepted by large numbers of those who had fought alongside Judah, as well as by Menelaus and his supporters.

Judah and his numerically reduced band, refusing to lay down arms, continued their struggle against what they saw as the oppression of their fellow Jews. Confident of doing God’s will, Judah and his soldiers retook the Temple against only token opposition, and cleansed it from the physical and spiritual filth it had suffered. On the twenty-fifth day of the month of Kislev in 164

BCE

, according to tradition exactly

three years from the day when a pagan sacrifice was first offered at the Temple, priests were again able to make offerings to God in accordance with biblical commands. This event became the basis for the holiday of Hanukkah or Rededication, which continues to be celebrated for eight days by Jews throughout the world.

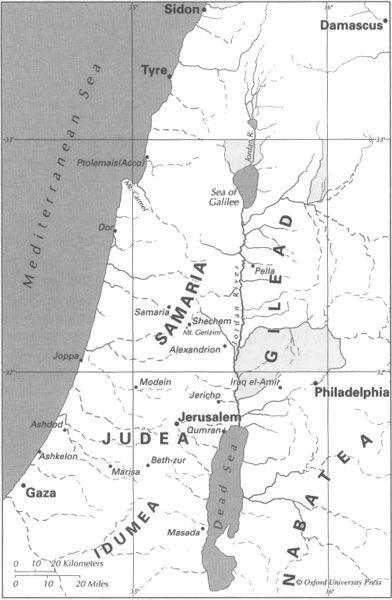

Palestine under the Hasmoneans

For most of those who celebrate Hanukkah today, the rededication of the Temple marks the end of the Maccabean revolt or at least the end of their knowledge of the revolt. In fact, the three years thus far covered constitute only the first part of a prolonged period marked by continued Syrian-Jewish fighting and increasingly bitter internal Jewish squabbling. The dangers inherent in hellenization became clearer at least for some, even as others made their peace with it. Judah, the only Hasmonean well known to the general public today, was followed by a succession of brothers, nephews, and other relations. The history of this Hasmonean period is complex.

Under the leadership of Judah and his brothers, the Maccabean forces continued to win an almost unbroken series of victories in their efforts to punish those who had persecuted Jews. As important as the cleansing of the Temple was, it was not their ultimate goal. They probably also drew strength from reports that Antiochus IV had died far away in the east at about the same time they were rededicating the Temple to God. Was that not another sign of divine approval?

Sometime in 163 Judah tried but failed to storm the Akra in Jerusalem, the garrison that housed foreign soldiers and civilians as well as Menelaus and his supporters. Lysias, who now controlled the Seleucid empire in the name of Antiochus IV’s young son Antiochus V, recognized that Judah was still a force to be reckoned with, but calculated that he could neutralize this force by deposing the increasingly unpopular and ineffectual Menelaus as high priest. In his place Lysias arranged for the appointment of Alcimus (his name in Greek; Yaqim was its Semitic version), who had a reputation for personal piety that contrasted favorably with Menelaus’s. Although Alcimus came from a priestly family, he was not a Zadokite. At this time Onias IV, son of Onias III who had been the last of the line of Zadok to occupy the highpriestly office, left Judea for Egypt, where he founded a temple at Leontopolis.

Other reverses followed Judah’s unsuccessful attempt to take the Akra. He met other military defeats, and one of his brothers, Eleazar, died in battle. Judah’s forces narrowly averted forcible eviction from the Temple. Apparently Lysias’s balanced policies were effectively diminishing Judah’s power and would eventually lead to the abandonment of his cause by all but his most die-hard followers. As it happened, however, Lysias’s power rather than Judah’s soon collapsed, as the Romans successfully promoted a brother of Antiochus IV as the new Seleucid monarch, deposing both Lysias and the young king he had more or less served. As Demetrius I, this ruler confirmed Alcimus as high priest and, like his predecessor, sought to gain decisive military advantage over Judah. What began as another series of Maccabean routs ended sometime later with the tragedy of Judah’s death in battle.

Shortly before his death Judah managed to engineer an extremely important alliance with the Romans. As friends and allies of the major world power of the day, the Jews could feel secure against further incursions by the Seleucids. At the same time, as witnessed by the very Syrian attack in which Judah died, the Seleucids were not deterred by the threat of Roman force in defense of their new Jewish allies. Jonathan, Judah’s oldest surviving brother, became leader of the remaining Hasmonean forces; their chief nemesis was Bacchides, the Seleucid governor of the region under whose command Judah had been killed. Things continued to look dire for the Maccabees when another of the brothers, John, fell in battle against Arab tribesmen. But thereafter the tide of battle turned again.