The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (70 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

In the problems which the Almighty sets his humble servants things hardly ever happen the same way twice over, or if they seem to do so, there is some variant which stultifies undue generalisation. The human mind, except when guided by extraordinary genius, cannot surmount the established conclusions amid which it has been reared. Yet we are to see, after eight months of inactivity on both sides, the Hitler inrush of a vast offensive, led by spearpoint masses of cannon-proof or heavily armoured vehicles, breaking up all defensive opposition, and for the first time for centuries, and even perhaps since the invention of gunpowder, making artillery for a while almost impotent on the battlefield. We are also to see that the increase of fire-power made the actual battles less bloody by enabling the necessary ground to be held with very small numbers of men, thus offering a far smaller human target.

* * * * *

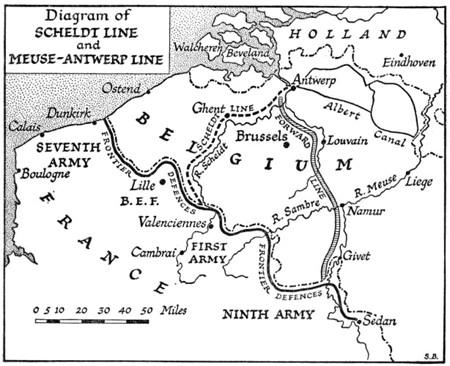

No frontier has ever received the same strategic attention and experiment as that which stretches through the Low Countries between France and Germany. Every aspect of the ground, its heights and its waterways, has been studied for centuries in the light of the latest campaign by all the generals and military colleges in Western Europe. At this period there were two lines to which the Allies could advance if Belgium were invaded by Germany and they chose to come to her succour; or which they could occupy by a well-planned secret and sudden scheme, if invited by Belgium. The first of these lines was what may be called the line of the Scheldt.

2

This was no great march from the French frontier and involved little serious risk. At the worst it would do no harm to hold it as a “false front.” At the best it might be built up according to events. The second line was far more ambitious. It followed the Meuse through Givet, Dinant, and Namur by Louvain to Antwerp. If this adventurous line was seized by the Allies and held in hard battles, the German right-handed swing of invasion would be heavily checked; and if their armies were proved inferior, it would be an admirable prelude to the entry and control of the vital centre of Germany’s munition production in the Ruhr.

Since the case of an advance through Belgium without Belgian consent was excluded on grounds of international morality, there only remained an advance from the common Franco-German frontier. An attack due eastward across the Rhine, north and south of Strasbourg, opened mainly into the Black Forest, which, like the Ardennes, was at that time regarded as bad ground for offensive operations. There was, however, the question of an advance from the front Strasbourg-Metz northeastward into the Palatinate. Such an advance, with its right on the Rhine, might gain control of that river as far north as Coblenz or Cologne. This led into good fighting country; and these possibilities, with many variants, had been a part of the war-games in the Staff Colleges of Western Europe for a good many years. In this sector, however, the Siegfried Line, with its well-built concrete pillboxes mutually supporting one another and organised in depth with masses of wire, was in September, 1939, already formidable. The earliest date at which the French could have mounted a big attack was perhaps at the end of the third week of September. But by that time the Polish campaign had ended. By mid-October the Germans had seventy divisions on the Western Front. The fleeting French numerical superiority in the West was passing. A French offensive from their eastern frontier would have denuded their far more vital northern front. Even if an initial success had been gained by the French armies at the outset, within a month they would have had extreme difficulty in maintaining their conquests in the East, and would have been exposed to the whole force of the German counter-stroke in the North.

This is the answer to the question, “Why remain passive till Poland was destroyed?” But this battle had been lost some years before. In 1938, there was a good chance of victory while Czechoslovakia still existed. In 1936, there could have been no effective opposition. In 1933, a rescript from Geneva would have procured bloodless compliance. General Gamelin cannot be the only one to blame because in 1939 he did not run the risks which had so erroneously increased since the previous crises, from which both the French and British Governments had recoiled.

The British Chiefs of Staff Committee estimated that the Germans had by September 18 mobilised at least 116 divisions of all classes, distributed as follows: Western Front, 42 divisions; Central Germany, 16 divisions; Eastern Front, 58 divisions. We now know from enemy records that this estimate was almost exactly correct. Germany had in all from 108 to 117 divisions. Poland was attacked by 58 of the most matured. There remained 50 or 60 divisions of varying quality. Of these, along the Western Front from Aix-la-Chapelle to the Swiss frontier, there stood 42 German divisions (14 active, 25 reserve, and 3 Landwehr). The German armour was either engaged in Poland or had not yet come into being, and the great flow of tanks from the factories had hardly begun. The British Expeditionary Force was no more than a symbolic contribution. It was able to deploy two divisions by the first and two more by the second week in October. In spite of the enormous improvement since Munich in their relative strength, the German High Command regarded their situation in the West while Poland was unconquered with profound anxiety, and only Hitler’s despotic authority, will-power, and five-times-vindicated political judgment about the unwillingness of France and Great Britain to fight induced or compelled them to run what they deemed an unjustified risk.

Hitler was sure that the French political system was rotten to the core, and that it had infected the French Army. He knew the power of the Communists in France, and that it would be used to weaken or paralyse action once Ribbentrop and Molotov had come to terms and Moscow had denounced the French and British Governments for entering upon a capitalist and imperialist war. He was convinced that Britain was pacifist and degenerate. In his view, though Mr. Chamberlain and M. Daladier had been brought to the point of declaring war by a bellicose minority in England, they would both wage as little of it as they could, and once Poland had been crushed, would accept the accomplished fact as they had done a year before in the case of Czechoslovakia. On the repeated occasions which have been set forth, Hitler’s instinct had been proved right and the arguments and fears of his generals wrong. He did not understand the profound change which takes place in Great Britain and throughout the British Empire once the signal of war has been given; nor how those who have been the most strenuous for peace turn overnight into untiring toilers for victory. He could not comprehend the mental or spiritual force of our island people, who, however much opposed to war or military preparation, had through the centuries come to regard victory as their birthright. In any case the British Army could be no factor at the outset, and he was certain that the French nation had not thrown its heart into the war. This was indeed true. He had his way, and his orders were obeyed.

* * * * *

It was thought by our officers that when Germany had completely defeated the Polish Army, she would have to keep in Poland some 15 divisions, of which a large proportion might be of low category. If she had any doubts about the Russian pact, this total might have to be increased to upwards of 30 divisions in the East. On the least favourable assumption Germany would, therefore, be able to draw over 40 divisions from the Eastern Front, making 100 divisions available for the West. By that time the French would have mobilised 72 divisions in France, in addition to fortress troops equivalent to 12 or 14 divisions, and there would be 4 divisions of the British Expeditionary Force. Twelve French divisions would be required to watch the Italian frontier, making 76 against Germany. The enemy would thus have a superiority of four to three over the Allies, and might also be expected to form additional reserve divisions, bringing his total up to 130 in the near future. Against this the French had 14 additional divisions in North Africa, some of which could be drawn upon, and whatever further forces Great Britain could gradually supply.

In air power, our Chiefs of Staff estimated that Germany could concentrate, after the destruction of Poland, over two thousand bombers in the West as against a combined Franco-British total of 950.

3

It was, therefore, clear that once Hitler had disposed of Poland, he would be far more powerful on the ground and in the air than the British and French combined. There could, therefore, be no question of a French offensive against Germany. What, then, were the probabilities of a German offensive against France?

There were, of course, three methods open. First, invasion through Switzerland. This might turn the southern flank of the Maginot Line, but had many geographical and strategic difficulties. Secondly, invasion of France across the common frontier. This appeared unlikely, as the German Army was not believed to be fully equipped or armed for a heavy attack on the Maginot Line. And thirdly, invasion of France through Holland and Belgium. This would turn the Maginot Line and would not entail the losses likely to be sustained in a frontal attack against permanent fortifications. The Chiefs of Staff estimated that for this attack Germany would require to bring from the Eastern Front twenty-nine divisions for the initial phase, with fourteen echelonned behind, as reinforcements to her troops already in the West. Such a movement could not be completed and the attack mounted with full artillery support under three weeks; and its preparation should be discernible by us a fortnight before the blow fell. It would be late in the year for the Germans to undertake so great an operation; but the possibility could not be excluded.

We should, of course, try to retard the German movement from east to west by air attack upon the communications and concentration areas. Thus, a preliminary air battle to reduce or eliminate the Allied air forces by attacks on airfields and aircraft factories might be expected, and so far as England was concerned, would not be unwelcome. Our next task would be to deal with the German advance through the Low Countries. We could not meet their attack so far forward as Holland, but it would be in the Allied interest to stem it, if possible, in Belgium.

We understand [wrote the Chiefs of Staff] that the French idea is that, provided the Belgians are still holding out on the Meuse, the French and British Armies should occupy the line Givet-Namur, the British Expeditionary Force operating on the left.

We consider it would be unsound to adopt this plan unless plans are concerted with the Belgians for the occupation of this line in sufficient time before the Germans advance…. Unless the present Belgian attitude alters and plans can be prepared for early occupation of the Givet-Namur

[

also called Meuse-Antwerp

]

line, we are strongly of opinion that the German advance should be met in prepared positions on the French frontier.

In this case it would, of course, be necessary to bomb Belgian and Dutch towns and railway centres used or occupied by German troops.

The subsequent history of this important issue must be recorded. It was brought before the War Cabinet on September 20, and after a brief discussion was remitted to the Supreme War Council. In due course the Supreme War Council invited General Gamelin’s comments. In his reply General Gamelin said merely that the question of Plan “D” (i.e., the advance to the Meuse-Antwerp line) had been dealt with in a report by the French delegation. In this report the operative passage was: “If the call is made in time the Anglo-French troops will enter Belgium, but not to engage in an encounter battle. Among the recognised lines of defence are the line of the Scheldt and the line Meuse-Namur-Antwerp.” After considering the French reply, the British Chiefs of the Staff submitted another paper to the Cabinet, which discussed the alternative of an advance to the Scheldt, but made no mention at all of the far larger commitments of an advance to the Meuse-Antwerp line. When this second report was presented to the Cabinet on October 4 by the Chiefs of Staff, no reference was made by them to the all-important alternative of Plan “D.” It was, therefore, taken for granted by the War Cabinet that the views of the British Chiefs of the Staff had been met and that no further action or decision was required. I was present at both these Cabinets, and was not aware that any significant issue was still pending. During October, there being no effective arrangement with the Belgians, it was assumed that the advance was limited to the Scheldt.

Meanwhile, General Gamelin, negotiating secretly with the Belgians, stipulated: first, that the Belgian Army should be maintained at full strength, and secondly, that Belgian defences should be prepared on the more advanced line from Namur to Louvain. By early November, agreement was reached with the Belgians on these points, and from November 5 to 14, a series of conferences was held at Vincennes and La Fère, at which, or some of which, Ironside, Newall, and Gort were present. On November 15, General Gamelin issued his Instruction Number 8, confirming the agreements of the fourteenth, whereby support would be given to the Belgians, “if circumstances permitted,” by an advance to the line Meuse-Antwerp. The Allied Supreme Council met in Paris on November 17. Mr. Chamberlain took with him Lord Halifax, Lord Chatfield, and Sir Kingsley Wood. I had not at that time reached the position where I should be invited to accompany the Prime Minister to these meetings. The decision was taken: “Given the importance of holding the German forces as far east as possible, it is essential to make every endeavour to hold the line Meuse-Antwerp in the event of a German invasion of Belgium.” At this meeting Mr. Chamberlain and M. Daladier insisted on the importance which they attached to this resolution, and thereafter it governed action. This was, in fact, a decision in favour of Plan “D,” and it superseded the arrangement hitherto accepted of the modest forward move to the Scheldt.