The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (65 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

The German Plan of Invasion — Unsound Polish Dispositions — Inferiority in Artillery and Tanks — Destruction of the Polish Air Force — The First Week — The Second Week — The Heroic Polish Counter-Attack — Extermination — The Turn of the Soviets — The Warsaw Radio Silent — The Modern Blitzkrieg — My Memorandum of September

21 —

Our Immediate Dangers — My Broadcast of October

1.

M

EANWHILE

, around the Cabinet table we were witnessing the swift and almost mechanical destruction of a weaker state according to Hitler’s method and long design. Poland was open to German invasion on three sides. In all, fifty-six divisions, including all his nine armoured divisions, composed the invading armies. From East Prussia the Third Army (eight divisions) advanced southward on Warsaw and Bialystok. From Pomerania the Fourth Army (twelve divisions) was ordered to destroy the Polish troops in the Dantzig Corridor, and then move southeastward to Warsaw along both banks of the Vistula. The frontier opposite the Posen Bulge was held defensively by German reserve troops, but on their right to the southward lay the Eighth Army (seven divisions) whose task was to cover the left flank of the main thrust. This thrust was assigned to the Tenth Army (seventeen divisions) directed straight upon Warsaw. Farther south again, the Fourteenth Army (fourteen divisions) had a dual task, first to capture the important industrial area west of Cracow, and then, if the main front prospered, to make direct for Lemberg (Lwow) in southeast Poland.

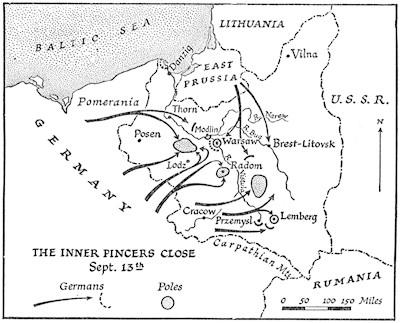

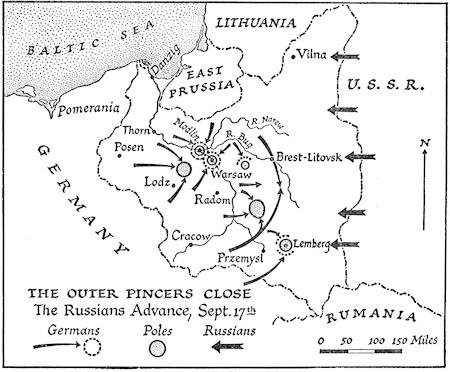

Thus, the Polish forces on the frontiers were first to be penetrated, and then overwhelmed and surrounded by two pincer movements: the first from the north and southwest on Warsaw; the second and more far-reaching, “outer” pincers, formed by the Third Army advancing by Brest-Litovsk to be joined by the Fourteenth Army after Lemberg was gained. Those who escaped the closing of the Warsaw pincers would thus be cut off from retreat into Rumania. Over fifteen hundred modern aircraft was hurled on Poland. Their first duty was to overwhelm the Polish air force, and thereafter to support the Army on the battlefield, and beyond it to attack military installations and all communications by road and rail. They were also to spread terror far and wide.

In numbers and equipment the Polish Army was no match for their assailants, nor were their dispositions wise. They spread all their forces along the frontiers of their native land. They had no central reserve. While taking a proud and haughty line against German ambitions, they had nevertheless feared to be accused of provocation by mobilising in good time against the masses gathering around them. Thirty divisions, representing only two-thirds of their active army, were ready or nearly ready to meet the first shock. The speed of events and the violent intervention of the German air force prevented the rest from reaching the forward positions till all was broken, and they were only involved in the final disasters. Thus, the thirty Polish divisions faced nearly double their numbers around a long perimeter with nothing behind them. Nor was it in numbers alone that they were inferior. They were heavily outclassed in artillery, and had but a single armoured brigade to meet the nine German Panzers, as they were already called. Their horse cavalry, of which they had twelve brigades, charged valiantly against the swarming tanks and armoured cars, but could not harm them with their swords and lances. Their nine hundred first-line aircraft, of which perhaps half were modern types, were taken by surprise and many were destroyed before they even got into the air.

According to Hitler’s plan, the German armies were unleashed on September 1, and ahead of them his air force struck the Polish squadrons on their airfields. In two days the Polish air power was virtually annihilated. Within a week the German armies had bitten deep into Poland. Resistance everywhere was brave but vain. All the Polish armies on the frontiers, except the Posen group, whose flanks were deeply turned, were driven backward. The Lodz group was split in twain by the main thrust of the German Tenth Army; one half withdrew eastward to Radom, the other was forced northwestward; and through this gap darted two Panzer divisions making straight for Warsaw. Farther north the German Fourth Army reached and crossed the Vistula, and turned along it in their march on Warsaw. Only the Polish northern group was able to inflict a check upon the German Third Army. They were soon out-flanked and fell back to the river Narew, where alone a fairly strong defensive system had been prepared in advance. Such were the results of the first week of the Blitzkrieg.

The second week was marked by bitter fighting and by its end the Polish Army, nominally of about two million men, ceased to exist as an organised force. In the south the Fourteenth German Army drove on to reach the river San. North of them the four Polish divisions which had retreated to Radom were there encircled and destroyed. The two armoured divisions of the Tenth Army reached the outskirts of Warsaw, but having no infantry with them could not make headway against the desperate resistance organised by the townsfolk. Northeast of Warsaw the Third Army encircled the capital from the east, and its left column reached Brest-Litovsk a hundred miles behind the battle front.

It was within the claws of the Warsaw pincers that the Polish Army fought and died. Their Posen group had been joined by divisions from the Thorn and Lodz groups, forced towards them by the German onslaught. It now numbered twelve divisions, and across its southern flank the German Tenth Army was streaming towards Warsaw, protected only by the relatively weak Eighth Army. Although already virtually surrounded, the Polish Commander of the Posen group, General Kutrzeba, resolved to strike south against the flank of the main German drive. This audacious Polish counter-attack, called the battle of the river Bzura, created a crisis which drew in, not only the German Eighth Army, but a part of the Tenth, deflected from their Warsaw objective, and even a corps of the Fourth Army from the north. Under the assault of all these powerful bodies, and overwhelmed by unresisted air bombardment, the Posen group maintained its ever-glorious struggle for ten days. It was finally blotted out on September 19.

In the meantime the outer pincers had met and closed. The Fourteenth Army reached the outskirts of Lemberg on September 12, and striking north joined hands on the seventeenth with the troops of the Third Army which had passed through Brest-Litovsk. There was now no loophole of escape for straggling and daring individuals. On the twentieth, the Germans announced that the battle of the Vistula was “one of the greatest battles of extermination of all times.”

It was now the turn of the Soviets. What they now call “Democracy” came into action. On September 17, the Russian armies swarmed across the almost undefended Polish eastern frontier and rolled westward on a broad front. On the eighteenth, they occupied Vilna, and met their German collaborators at Brest-Litovsk. Here in the previous war the Bolsheviks, in breach of their solemn agreements with the Western Allies, had made their separate peace with the Kaiser’s Germany, and had bowed to its harsh terms. Now in Brest-Litovsk, it was with Hitler’s Germany that the Russian Communists grinned and shook hands. The ruin of Poland and its entire subjugation proceeded apace. Warsaw and Modlin still remained unconquered. The resistance of Warsaw, largely arising from the surge of its citizens, was magnificent and forlorn. After many days of violent bombardment from the air and by heavy artillery, much of which was rapidly transported across the great lateral highways from the idle Western Front, the Warsaw radio ceased to play the Polish National Anthem, and Hitler entered the ruins of the city. Modlin, a fortress twenty miles down the Vistula, had taken in the remnants of the Thorn group, and fought on until the twenty-eighth. Thus, in one month all was over, and a nation of thirty-five millions fell into the merciless grip of those who sought not only conquest but enslavement, and indeed extinction for vast numbers.

We had seen a perfect specimen of the modern Blitzkrieg; the close interaction on the battlefield of army and air force; the violent bombardment of all communications and of any town that seemed an attractive target; the arming of an active Fifth Column; the free use of spies and parachutists; and above all, the irresistible forward thrusts of great masses of armour. The Poles were not to be the last to endure this ordeal.

* * * * *

The Soviet armies continued to advance up to the line they had settled with Hitler, and on the twenty-ninth the Russo-German Treaty partitioning Poland was formally signed. I was still convinced of the profound, and as I believed quenchless, antagonism between Russia and Germany, and I clung to the hope that the Soviets would be drawn to our side by the force of events. I did not, therefore, give way to the indignation which I felt and which surged around me in our Cabinet at their callous, brutal policy. I had never had any illusions about them. I knew that they accepted no moral code, and studied their own interests alone. But at least they owed us nothing. Besides, in mortal war anger must be subordinated to defeating the main immediate enemy. I was determined to put the best construction on their odious conduct. Therefore, in a paper which I wrote for the War Cabinet on September 25, I struck a cool note.

Although the Russians were guilty of the grossest bad faith in the recent negotiations, their demand, made by Marshal Voroshilov that Russian armies should occupy Vilna and Lemberg if they were to be allies of Poland, was a perfectly valid military request. It was rejected by Poland on grounds which, though natural, can now be seen to have been insufficient. In the result Russia has occupied the same line and positions as the enemy of Poland, which possibly she might have occupied as a very doubtful and suspected friend. The difference in fact is not so great as might seem. The Russians have mobilised very large forces and have shown themselves able to advance fast and far from their pre-war positions. They are now limitrophe with Germany, and it is quite impossible for Germany to denude the Eastern Front. A large German army must be left to watch it. I see General Gamelin puts it at least twenty divisions. It may well be twenty-five or more. An Eastern Front is, therefore, potentially in existence.

In a broadcast on October 1, I said:

Poland has again been overrun by two of the Great Powers which held her in bondage for a hundred and fifty years, but were unable to quench the spirit of the Polish nation. The heroic defence of Warsaw shows that the soul of Poland is indestructible, and that she will rise again like a rock, which may for a time be submerged by a tidal wave, but which remains a rock.

Russia has pursued a cold policy of self-interest. We could have wished that the Russian armies should be standing on their present line as the friends and allies of Poland instead of as invaders. But that the Russian armies should stand on this line was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is there, and an Eastern Front has been created which Nazi Germany does not dare assail….

I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest. It cannot be in accordance with the interest or the safety of Russia that Germany should plant herself upon the shores of the Black Sea, or that she should overrun the Balkan States and subjugate the Slavonic peoples of Southeastern Europe. That would be contrary to the historic life-interests of Russia.