Spiritual Care: A Guide for Caregivers (10 page)

Read Spiritual Care: A Guide for Caregivers Online

Authors: Judith Allen Shelly

Faith prepares us for ministry to others, but we also need to

learn the specific skills of active listening, empathy, vulnerability,

humility and commitment. Furthermore, it will take practice

before those skills become second nature. Rosalie, the church visitor in the opening story, had faith, but she lacked the skills to support others in their suffering.

Listening is an acquired skill. It involves hearing and understand ing not only what people are saying but also what they are afraid

to say. Careful listening enables you to perceive some of the reasons behind another's verbal and nonverbal communication.

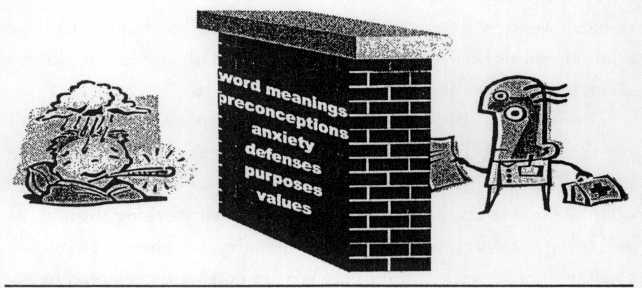

At times unconscious barriers may cause us to use selective listening-hearing only what we feel equipped to handle. As we become

aware of these barriers (see figure 2), we can begin to overcome

them and hear what others are really saying.

Figure 2. Barriers to listening

Word meanings may be a barrier to hearing a person's expression

of spiritual needs. Each Christian tradition has a unique vocabulary for describing important aspects of faith and practice. For

instance, the terms describing a person's faith relationship with

God may differ. "Accepting Christ," "becoming a believer," "getting saved," "being born again," "being baptized" and "awakening

to new life in Christ" may seem synonymous to some people; to

others only one of those terms may be acceptable. The word spirituality itself may mean many different things. Lingo may be a convenient shortcut in communication, but only if you are sure a term

means the same thing to the other person as it does to you.

For example, Joann felt alone and afraid when she was admitted to the hospital for tests. However, she felt a flood of relief when she saw a gold cross on her nurse's lapel. She asked the

nurse tentatively if she was a Christian. "Yes!" she replied. "I'm a

born-again, Bible-believing Christian; are you?" While Joann had

a deep faith commitment and spent hours reading her Bible, the

terms the nurse used were associated in her mind with manipulative TV evangelists. She retreated into her quiet fear and did not

respond.

Preconceptiorw prevent us from hearing clearly what others are

saying. The most overriding preconception affecting spiritual care

is the idea that anyone who is truly serious about a relationship

with God must believe what I believe and behave as I behave.

For instance, I once cared for a sixty-eight-year-old man whose

verbal communication consisted of demands to serve him, delivered with a liberal sprinkling of profanity. One day when I did not

respond immediately to his command, he threw the contents of his

urinal at me. I was furious and avoided him as much as possible

after that. Later, reading his chart I discovered that he was a

retired seminary professor. The combination did not seem compatible to me, and I judged him severely in my mind. Several days

later, his wife was in the room when he demonstrated similar

behavior. I could see tears in her eyes. She followed me out of the

room and explained, "He was never like this before. He is a man

of God, but after the cancer spread to his brain, his personality

changed. I'm so sorry !"

Anxiety creates further barriers to listening. When you are anxious, you focus on yourself rather than on the person in need. Any

time we are faced with a new situation or learning new skills, anxiety about the task we are performing may prevent us from hearing the other person. For this reason, we may not become

involved in meeting spiritual needs when we are immersed in a

new situation. Once we become comfortable with ourselves and the situation, we will be able to hear the other person's expression

of anxiety.

Closely related to anxieties are personal defenses. When a person

offends us or attacks something we hold dear, we tend to put up

defenses to protect ourselves and our values. For instance, a person's expression of anger toward God might cause you to respond

by defending God rather than hearing the person's cry of desperation. Another person's seductive behavior might cause you to

avoid him rather than setting limits and staying to listen.

While it is important to set goals for spiritual care, predetermined purposed may also create a barrier to listening. For instance,

a church visitor may go to a homebound member's home intending to play the videotape of Sunday's worship service. Realizing

that he still has one more shut-in to visit, he may put the tape in

the VCR and not hear the person's quiet remark, "My toe is turning black. The doctor says it may have to be removed."

Finally, values prevent us from listening with open ears. We are

constantly meeting people whose values are different from our

own. It is often difficult to feel compassion for someone who has

violated our own moral standards and suffered for it. We tend to

think that person deserves what he got. For example, a nurse who

disapproves of abortion may be unable to listen compassionately

to the fears and concerns of a woman undergoing the procedure.

Many persons with AIDS have experienced extreme prejudice,

regardless of how they contracted the disease.

All of us have certain values that govern our moral behavior.

These values arise out of our beliefs, experiences and environment. When we force our values on other people, we unconsciously assume that their beliefs, experiences and environment

are the same as our own. To suspend judgment so that we may listen to the hurts, fears and concerns of others may show us that we too might have acted in a similar manner, had we been subjected

to the same influences. Listening sensitively does not require us to

agree with the other person or condone behavior that violates our

moral values, but it does enable us to empathize with people.

Through empathy we can become agents of creative change.

Empathy is the ability to understand what a person is feeling and

to communicate that understanding while remaining objective

enough to analyze the situation and provide assistance. Empathy

is a process involving both the mind and the emotions.

The first stage in the process is assessment-collecting the facts

about the person's affect, behavior, physical condition, environment, support systems and so on.

But just gathering the facts does not enable us to truly care. For

example, Betty seemed accident-prone. She no sooner recovered

from one injury or minor surgery than another occurred. During a

church softball game, parish nurse Marty Jacobs watched Betty

smash a soft drink bottle against a large rock, then immediately

begin picking up the pieces with her bare hands. Marty warned

Betty to stop collecting the glass, then went into the church building to find a broom and dustpan. When she returned, Betty sat

holding a tissue over a large laceration on her palm. Marty was so

annoyed with the dynamics of the situation, and so intent on

cleaning and dressing the wound, that she almost missed it when

Betty told her, "My husband left me again yesterday. We had an

argument, and he hit me."

Suddenly Marty realized that this was more than an offhand

comment. As it hit full force, Marty felt a knot forming in the pit

of her stomach, and anger welled up at Betty's husband, Wayne.

She applied pressure to the wound and looked at Betty. "Tell me what happened." At this point, Marty entered the second stage of

the empathy process; she felt sympathy. She moved from focusing

purely on the facts and the physical situation to sensing the feelings. She also began to feel Betty's pain.

In the sympathy stage we respond as if we were the other person. But if we stop at this point, we can become as immobilized as

the hurting person we are trying to help. If Marty had stopped at

the sympathy stage, she might have responded, "That rotten

snake! How could he do that again? Why don't you just divorce

the jerk?" Our inner responses depend on our own background

and resources. While Marty's response was to become angry with

Wayne and want to retaliate, Betty still loved Wayne and wanted

him to come back to her. Had Marty reacted out of her own feelings, Betty would probably have felt that she needed to defend

Wayne. Instead, Marty gave her the opportunity to share what

she really felt.

At the third and final stage, empathy, we put the facts and the

feelings together to examine them objectively. In so doing, we

begin to discern why Betty feels as she does. Here the focus is

back on Betty's needs and feelings. Marty can now support Betty

effectively and encourage her toward constructive action. By providing an opening for Betty to talk further about what happened,

Marty can understand the situation better and guide Betty toward

the help she needs to overcome an abusive marriage.

The process of empathy becomes almost second nature in a sensitive, mature caregiver. But as learners we need to look at the

stages to discover where the difficulty lies if our responses do fall

short of empathy. If you find yourself remaining cool and aloof

with people in need of help, spend some time considering what

barriers in your own emotions prevent you from entering into the

concerns of others. Thinking back on crises you have encoun tered, how you felt and what kind of help you wanted at the time

may increase your awareness of the feelings and needs of others.

On the other hand, if you find yourself overwhelmed by your

concern for others and depressed by their problems, focus on

assessment. First, examine the memories and feelings that the

other person's situation triggers in you. Write down what you are

thinking and feeling. Talk to a close friend, pastor or counselor.

Next, discover the resources available to deal with the problems.

Spend more time looking at the objective facts. Research the creative alternatives. Read books about people who have endured

suffering and overcome serious handicaps to lead meaningful and

productive lives. Then you will be more able to move beyond sympathy to full empathy.

Developing empathy requires vulnerability. To "feel with" another

person opens us to the possibility that we too will experience pain.

To offer ourselves as a resource to other people creates the likelihood that at some time we will be rejected. Compassionate presence involves lending people our strength until they can regain

their own strength. We may feel drained in the process. Caregivers who are vulnerable are those who are willing to open themselves up to rejection, criticism and pain, as well as to the joy and

praise of other people, as they respond to people in a caring relationship.

Jocelyn Collins is a good example of vulnerability. Jocelyn volunteered in a church-related women's shelter. Her desire to serve

grew out of her experience as a young woman. While she was a

college student she had lived with an abusive boyfriend. When she

became pregnant, her boyfriend forced her to have an abortion.

Afterward he called her a worthless slut, and the abuse intensified. When she finally began to fear for her life, she left him, finding

help in a women's shelter. Now married with two small children,

she had moved to a new community and a new church where no

one knew her history.

As Jocelyn tried to talk with Kay, a new resident in the shelter,

she found herself reeling inside as Kay spewed venom at her.

"How could you possibly understand? You're so sweet and innocent. You -with your nice husband and comfortable home! You

don't know what it's like to be in this situation."

Jocelyn could see the pastor's wife within earshot. She really

did not want to reveal all the ugliness of her past, knowing she

would probably have to explain it all over again, but she knew she

had to be vulnerable. "Yes, Kay, I do. Ten years ago, I was in a

similar situation. I felt so alone and afraid."

Kay's attitude shifted immediately. She poured out her fears,

concerns, hopes and dreams -her love for her boyfriend and fear

of losing him, and well as her fear of his abuse. "Do you really

think I can get through this?" she implored.

Jocelyn put her hand on Kay's shoulder, "With God's help, I

know you can." She continued to visit Kay regularly, simply listening to her and encouraging her, until Kay gained the confidence

and financial security to move to another state with her children.

Allowing ourselves to be vulnerable forces us to recognize our

humanity. As human beings we are vulnerable. We hurt, we fail,

we are intimidated by death, we experience pain both physically

and emotionally-we need someone to support us as we support

others. To function as if we were not vulnerable is destructive to

our own emotional health and creates barriers between us and

those we want to help. By being honest about her own past, Jocelyn opened a whole new avenue of ministry with others, but she

also gained continuing support for herself. When others know the worst about you and still love you, you can live without fear of

being "found out."

Recognizing our own humanity is also an expression of humility.

To know we are human is to recognize our limits as well as our

strengths. Humility protects us from the temptation to feel omnipotent and indispensable. It enables us to trust others enough to

provide aspects of care that are beyond our own expertise. Compassionate presence with another person can develop a bond so

strong that eventually a caregiver begins to feel "ownership" of the

other person, which then creates a sense of resentment when others attempt to help. At this point our presence ceases to be compassionate and becomes manipulative. It also prevents the needy

person from receiving the benefit of support and affection from

others. From a spiritual perspective, humility is the realization

that God can use another person in someone's life just as easily as

he can use me.