Resident Readiness General Surgery (62 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

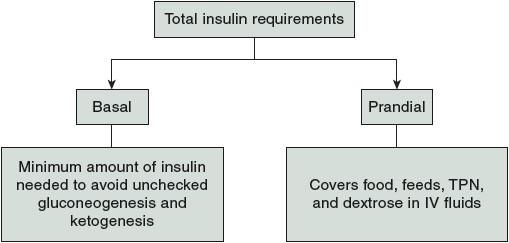

Figure 47-1.

Components of total insulin requirements.

3.

By definition, these patients are insulin deficient and therefore require a constant basal supply of insulin to avoid entering diabetic ketoacidosis. Adult Type 1 diabetics are frequently very familiar with how much insulin their bodies require and are very comfortable recognizing sensations of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Often these patients will be able to subcutaneously administer insulin to themselves via an insulin pump that lets them control the precise dosage of insulin administered to their bodies. In my experience, it is best to work/negotiate with these patients and let them control their own insulin delivery. If they are eating, these patients should be on a long-acting insulin (such as NPH or lente) that they administer in the morning or evenings. In addition, a bolus of short-acting insulin (such as lispro or aspart) is given before or after eating to cover carbohydrates that will be or were consumed. If Type 1 diabetics are not eating, it is essential that they still receive their basal insulin requirements! For many patients, the basal insulin requirement will not change even when they are NPO. If you are unsure or the patient is particularly brittle, you can start at half of the basal insulin requirement and increase accordingly. Fluctuations in blood glucose levels secondary to dextrose in intravenous fluids or TPN should be covered by a sliding insulin scale. Note that patients who had a recent pancreatectomy or who have severe pancreatic dysfunction may now be considered Type 1 diabetics.

4.

Unlike Type 1 diabetics, these patients have a problem with insulin resistance. Initially, Type 2 diabetics have high levels of basal insulin secretion, but may

need additional prandial insulin to defeat this resistance. When eating, these patients should be on all of their insulin sensitizers and secretagogues (such as metformin, sulfonylureas, glitazones, exendin-4, etc) in addition to their basal and nutritional insulin requirements to maintain glucose levels less than 180 mg/dL. Over time, these patients may lose some of their insulin production capacity and therefore require supplemental basal insulin as well. Interestingly, the glycemic profile of Type 2 diabetics is frequently diet related and their total insulin needs typically decrease when they are NPO even without their normal oral diabetes agents. Therefore, Type 2 diabetics who are NPO may only require a correction dosage or sliding-scale coverage. However, it is important to remember that these patients still have insulin resistance so their overall insulin requirements may still be quite high.

5.

Often, these patients were precariously close to requiring insulin at home, but either did not have regular glucose checks or the stress of surgery has pushed them into requiring insulin. Patients may also receive postoperative corticosteroids that can exacerbate preexisting poor glycemic control. Starting de novo insulin treatments may seem daunting to new resident physicians, but is actually quite straightforward.

First, check a HbA1C to get a rough idea of preoperative glycemic control and then multiply the body weight in kilograms by 0.4 U of insulin (0.3 if very elderly, 0.5 if morbidly obese) to get a total daily insulin requirement. Give half of the daily requirement as glargine at night or in divided NPH dosages every 12 hours. If the patient is able to eat, give the other half as short-acting insulin divided into 3 equal correctional dosages shortly before meals. The patient should also be restarted on his or her oral diabetic agents. The patient’s nurse should be asked to record the patient’s blood glucose levels prior to giving all insulin injections. A glucose reading <70 mg/dL indicates that the patient is receiving too much insulin and the dosages should be adjusted accordingly. Patients should be appropriately counseled that it is unlikely they will go home on insulin, but may require insulin therapy in the future if their diabetes worsens. If the patient will be NPO for long periods of time and therefore requires TPN or PPN, insulin should be calculated based on your institution’s protocols and included directly with the TPN. Any exogenous basal or prandial insulin should be used with caution in patients on TPN/PPN as these infusions are frequently disrupted and the patient could become quickly hypoglycemic.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

Surgical patients require good glycemic control to avoid many types of postoperative complications.

A useful framework to think about insulin replacement therapy is that each patient needs both basal and prandial insulin. Basal therapy consists of

long-acting insulins given in the morning, nighttime, or both. Ideally, prandial therapy should be given before or between meals.

Sliding-scale insulin coverage is a substandard, reactive form of prandial therapy, but may be sufficient in surgical patients who are NPO.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Prolonged hyperglycemia in diabetic patients has been associated with all of the following

except

?

A. Phagocyte dysfunction

B. Endothelial cell dysfunction

C. Platelet activation

D. Vascular inflammation

E. Increased catecholamine production

2.

You are going to start insulin therapy on a 55-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes who weighs 200 kg. What are his estimated total daily insulin needs?

A. 40 U of insulin

B. 60 U of insulin

C. 80 U of insulin

D. 100 U of insulin

E. 120 U of insulin

3.

Which of the following complications will most likely occur if you do not give an insulin-dependent diabetic (Type 1) his or her basal amounts of insulin?

A. Diabetic ketoacidosis

B. Stroke

C. Myocardial infarction

D. Wound infection

E. Pulmonary insufficiency

Answers

1.

E

. Increased catecholamine production has not been linked to prolonged hyper-glycemia in diabetic patients.

2.

C

. His estimated total daily insulin requirement is approximately 0.4 U/kg × 200 kg = 80 U of insulin.

3.

A

. Lack of insulin in Type 1 diabetics leads to ketoacidosis that features ketonemia, hyperglycemia, and an anion gap metabolic acidosis. This condition can be fatal if not recognized early.

A 65-year-old Female Presenting for Preoperative Evaluation

A 65-year-old Female Presenting for Preoperative Evaluation

Jahan Mohebali, MD

A 65-year-old female with a PMH notable for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and recent coronary stent placement presents to your office for preoperative evaluation for repair of a ventral hernia. She has had the hernia for many years; however, it has recently begun to cause some occasional discomfort after she stands for prolonged periods of time. The hernia has always been easily reducible, and she has had no previous episodes of bowel obstruction related to it. With regard to her cardiovascular history, in addition to the paroxysmal a-fib, she reports poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes, and a transient ischemic attack a few years ago. Since that time, she has been taking warfarin. One month ago she underwent cardiac stress testing that demonstrated ST changes in the inferior leads resulting in cardiac catheterization and deployment of a drug-eluting stent. An echocardio-gram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35%. Plavix was added to her medical regimen and she has been doing quite well since that time. She denies any ongoing chest pain or dyspnea on exertion.

1.

Should this patient’s hernia repair be delayed?

2.

If the patient undergoes an elective hernia repair 12 months later, should Plavix and warfarin be held?

3.

How many days before an operation should antiplatelet medication be held?

4.

If the decision is made to stop the patient’s warfarin, how many days prior to the operation should it be held?

5.

What is the patient’s CHADS2 score, and what score typically suggests that a patient should receive bridging therapy with heparin?