Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (70 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Now comes word that a British fleet is at the other end of the lake threatening Sackets Harbor. The attack fails, but the Americans panic, briefly setting fire to the partially built warship

General Pike

, thus delaying its launch date. That is enough for Chauncey, who leaves the Niagara frontier, taking all his ships and two thousand troops, a defection that allows Vincent’s army to reach the protection of the heights above Burlington Bay. If the Americans are to dislodge them, they must now proceed by land.

STONEY CREEK, UPPER CANADA, JUNE 5, 1813

To young Billy Green and his brother Levi, the war is a lark. The older settlers may be in a state of panic, believing with some reason that the British are about to desert them, but when the Green brothers hear that the Americans are only a few miles away they cannot restrain their excitement. Nothing will do but that they have a good look at the advancing army.

With the fall of Fort George, the greater part of the Niagara peninsula has been evacuated by the British army. The Americans have taken Fort Erie and are pushing up the peninsula—have already reached Forty Mile Creek, some thirty-one miles from Newark. General Vincent’s army has retired to Burlington Heights and dug in, but there is not much hope that his seven hundred regular troops can hold the position against three thousand of the enemy. The militia have been disbanded and sent home—deserted by the British, in the opinion of Captain William Hamilton Merritt, whose volunteer horsemen still continue to harass the forward scouts of the advancing enemy. Like many others, Merritt is convinced that the army will retreat to Kingston, leaving all of the western province in the hands of the invaders.

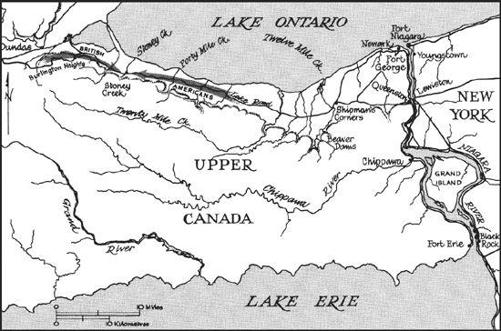

The Niagara Peninsula, 1813

None of this concerns young Billy, a high-spirited youth of nineteen, youngest of Adam Green’s seven children. Left motherless almost at birth, shortly after the family moved up from New Jersey, he is known as a loner and a woodsman who can shinny up any tree and swing from branch to branch like a monkey. Now, at six o’clock on a humid spring morning, the two brothers clamber up the Niagara escarpment and make their way south until they reach a point above the American camp at the mouth of Forty Mile Creek.

At noon, hidden from view, they watch the Americans marching by, wait until almost all have passed, then begin to yell like Indians—a sound that sends a chill through the stragglers. “I tell you those simple fellows did run,” is the way Billy describes it.

Back along the ridge the brothers scamper, then scramble back down to the road the soldiers have just passed over. Here they run into a lone American, one boot off, tying a rag onto his blistered foot. As he grabs for his musket, Levi Green belabours him with a stick. The resultant yells of pain draw a rattle of musket fire from the rearguard, whereupon the brothers dash back up the slope, whooping Indian-style, until they reach Levi’s cabin on a piece of bench land halfway up the escarpment.

The sound of warwhoops and gunfire draws several settlers from their homes, and a small crowd looks down from the brow of the hill at the Americans marching through the village of Stoney Creek—a scattered huddle of log cabins and taverns. Some of the marchers halt long enough to fire at the hill, one musket ball coming so close that it strikes a fence rail directly in front of Levi’s wife, Tina, who is holding their oldest child, Hannah, in her arms.

Now the two descend to the village where their sister, Kezia Corman, reports that the Americans have taken her husband, Isaac, a prisoner. Billy starts off at a dead run across Stoney Creek, whistling for his brother-in-law. A few moments later he hears an owl hoot and knows it is Isaac. The missing man has made his escape by pretending to be friendly to the American cause—a plausible enough pretence in this province.

Isaac simply told the major who captured him that he is a Kentuckian and first cousin to William Henry Harrison. It is true; his mother is Harrison’s father’s sister. The major promptly released him and when Corman explained that he could not get through the American lines, cheerfully gave him the countersign of the day which, appropriately enough, is made up of the first syllables of Harrison’s name:

Wil-Hen-Har

.

Billy Green is now in possession of a vital piece of information. He knows what he must do—get a message to the British at Burlington Heights. Back he goes to Levi’s farm, borrows his brother’s horse, Tip, rides him as far as he can, ties him to a fence, and makes his way to the British lines on foot.

At this very hour, the British are planning to gamble on a night attack against the American camp. Lieutenant-Colonel Harvey has already reconnoitred the enemy position and believes it to be vulnerable. Harvey is by far the most experienced officer in the division. At thirty-four, he is thirteen years younger than his commander, Vincent, but has spent more than half his life on active service in Holland, France, Ceylon, Egypt, India, and the Cape of Good Hope. The illegitimate son of a peer, Lord Paget (so it is whispered), he is married to the daughter of another, Lord Lake.

In an army that has its fair complement of laggards, the hawk-faced Harvey stands out. Landing at Halifax in the dead of the previous winter, he pushed on to Quebec on snowshoes. He has served in enough campaigns to hew to two basic military principles. He is a firm believer first in “the accurate intelligence of the designs and movements of the enemy, to be procured at any price,” and second, in “a series of bold, active, offensive operations by which the enemy, however superior in numbers, would himself be thrown upon the defensive.”

Harvey now puts these twin precepts into operation. He has not only reconnoitred the enemy himself, but also one of his subalterns, James FitzGibbon of the 49th, an especially bold and enterprising officer, has apparently disguised himself as a butter pedlar and actually entered the American camp and noted the dispositions of troops and guns.

Harvey is able to report to Vincent that the Americans are badly scattered, that their cannon are poorly placed, that their cavalry is too far in the rear to be useful. He urges an immediate surprise attack by night at bayonet point. It is, in fact, their only chance. Ammunition is low; the American fleet may arrive at any moment. If that happens the army must retreat quickly or face annihilation. Vincent agrees and bowing to Harvey’s greater experience and knowledge of the ground sensibly puts him in charge of the assault.

Now, thanks to Billy Green, Harvey has the countersign. He asks Billy if he knows the way to the American camp.

“Every inch of it,” replies Billy proudly.

Harvey gives him a corporal’s sword, which Billy will keep for the rest of his long life, and tells him to take the lead. It is eleven-thirty. The troops, sleeping on the grass, are aroused, and the column sets off on a seven-mile march through the Stygian night. It is so dark the men can scarcely see each other, the moon masked by heavy clouds, the tall pines adding to the gloom, a soft mist blurring the trails. Only the occasional flash of heat lightning alleviates the blackness.

Their footfalls muffled by the mud of the trail, the troops plod forward in silence. Harvey has cautioned all against uttering so much as a whisper and has also taken care to order all flints removed from firelocks to prevent the accidental firing of a musket. Billy Green, loping on ahead, finds he has left the column behind and must retrace his steps to urge more speed; otherwise it will be daylight before the quarry is flushed. Well, someone in the ranks is heard to mutter, that will be soon enough to be killed.

By three, on this sultry Sunday morning, Harvey’s force has reached the first American sentry post. After it is over nobody can quite remember the order of events. Someone fires a musket. At least one sentry is quietly bayoneted. (“Run him through,” whispers Harvey to Billy Green.) Another demands the countersign and Billy gives it to him, at the same time seizing his gun with one hand and dispatching him with his new sword held in the other. An American advance party of fifty men, quartered in a church, is overpowered and taken prisoner.

The Americans are camped on James Gage’s field, a low, grassy meadow through which a branch of Stoney Creek trickles. The main road, down which the British are advancing, runs over the creek and ascends a ridge, the crest marked by a tangle of trees and roots behind which most of the American infantry and guns are located, their position secured by hills on one side, a swamp on the other.

Directly ahead, in a flat meadow below the ridge, the British can see the glow of American campfires. Moving forward to bayonet the sleeping enemy, they discover to their chagrin that the meadow is empty. The Americans have left their cooking fires earlier to take up a stronger position on the ridge.

In the flickering light of the abandoned fires the attackers fix flints; but by now all hope of surprise has been lost, for the attackers are easily spotted in the campfire glow. As they dash forward, whooping like Indians to terrify the enemy (who believe, and will continue to believe, that they have been attacked by tribesmen), they are met by a sheet of flame. In an instant all is confusion, the musket smoke adding to the thickness of the night, the howls of the British mingling with the sinister

click-click-click

of muskets being reloaded. All sense of formation is lost as some retire, others advance, and friend has difficulty distinguishing foe in the darkness.

The enterprising FitzGibbon, seeing men retreating on the left, runs along the line to restore order. The left holds, and five hundred Americans are put to flight; but the British on the right are being pushed back by more than two thousand. The guns on the ridge above are doing heavy damage. Yet, as Harvey has surmised, the American centre is weak, for the guns do not have close infantry support.

Major Charles Plenderleath of the 49th, a veteran of the battle of Queenston Heights, realizes that his men have no chance unless the guns are captured. He calls for volunteers. Alexander Fraser, a huge sergeant, only nineteen, gathers twenty men and with Plenderleath sprints up the road to rush the guns. Two volleys roar over their heads, but before the gunners can reload they are bayoneted. Plenderleath and Fraser cut right through, driving all before

them, stabbing horses and men with crazy abandon. Fraser alone stabs seven, his younger brother four. The American line is cut, four of the six guns captured, one hundred prisoners seized.

The Battle of Stoney Creek

The American commander, Brigadier-General John Chandler, a former blacksmith, tavernkeeper and congressman, owes his appointment to political influence rather than military experience, of which he has none. He will spend the rest of his life defending his actions this night. As an associate remarks, “the march from the anvil and the dram shop in the wane of life to the dearest actions of the tented field is not to be achieved in a single campaign.”

The General is up at the first musket shot, galloping about on his horse, shouting orders, trying to rally his badly dispersed troops. He can see the British outlined against the cooking fires but not much more. On the crest of the hill, pocked by unexpected depressions and interspersed with stumps, brushwood, fence rails and slash, his horse stumbles, throws him to the ground, knocking him senseless. When he recovers, all is confusion. Badly crippled, he hobbles about in the darkness crying, “Where is the line? Where is the line?” until he sees a group of men by the guns, which to his dismay do not seem to be firing. He rushes forward, mistaking the men of the British 49th for his own 23rd, realizes his error too late, tries to hide under

a gun carriage, and is ignominiously hauled out by Sergeant Fraser, who takes his sword and makes him prisoner.

Chandler’s second-in-command, Brigadier-General William Winder—a former Baltimore lawyer and another political appointee—is also lost. He too finds himself among the enemy, pulls a pistol from its holster, and is about to fire when Fraser appears.

“If you stir, Sir, you die,” says the sergeant.

Winder takes his word for it, throws down his pistol and sword, and surrenders.