Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (69 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

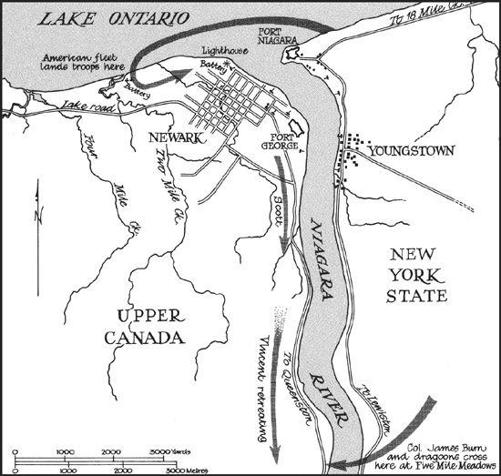

The enemy ships are manoeuvring to catch the British batteries in a crossfire. The effect is shattering. The battery at the lighthouse manages to fire off a single shot before it is destroyed. Another at Two Mile Creek has to be abandoned. As the fleet continues its majestic movement forward, three schooners move close to shore to cover the landing at Crookstown, a huddle of farmhouses near the mouth of Two Mile Creek. In a thicket overlooking this potential invasion point Vincent has hidden a guard of fifty Mohawk under

their celebrated Scottish chief, John Norton. A hail of missiles fired at point-blank range pierces the covert, killing two Indians and wounding several before the main body flees.

On board the American flagship

Madison

, Major-General Dearborn, too ill to lead the attack himself, watches nervously as the assault boats move toward the shore. He sees a young naval officer, Oliver Hazard Perry, directing the fire of the schooners from an open boat, standing tall in the stern in full uniform, oblivious to enemy musket fire. Perry is rowed from vessel to vessel, telling each where to anchor to achieve the best field of fire. That done, he boards

Madison

, determined to have nothing further to do with an invasion he believes to be badly planned and ineptly mounted.

Gazing at the churning waters below, Perry falls prey to conflicting emotions. He chafes for action, has come all the way from Lake Erie to take charge of the sailors and marines in the assault—rowing for weary hours under the threat of British cannon, then galloping bareback through dense forests in a driving storm—only to find his advice ignored. He has no intention of taking the blame for any disaster that results.

But Perry has a sudden change of heart. The one man he admires, Colonel Winfield Scott, Dearborn’s adjutant-general, is in danger. Scott stands in the leading flatboat with Benjamin Forsyth’s green-clad riflemen, the same sharpshooters who led the attack on York, but Perry sees that he is being blown off course and is about to miss the landing point. If Scott and the entire advance guard are not ordered immediately to pull to the windward, they will lose the protection of the covering schooners.

Gone, suddenly, are all Perry’s scruples. He begs to be allowed to avert the disaster. Dearborn assents, and Perry leaps back into his gig, picks up Scott, and with his help herds the scattered assault craft back on course.

As the advance guard pulls for the bank, Perry rows swiftly over to

Hamilton

, the closest schooner to shore. He is no sooner alongside than a lookout on the mast shouts that the whole British army is advancing on the double to thwart the landing.

The Capture of Fort George

Most of the American officers do not believe the British will make a stand. This view is reinforced by the presence of a high bank, which conceals the defending troops. But Perry senses danger, sets off to warn Scott, rows hard past

Hamilton

, and slips in and out between the advancing ships. Just as he reaches the lead assault boat, the British appear on the bank and fire a volley, most of which goes over the heads of the riflemen. Confusion follows. Some of the oarsmen stop rowing while the soldiers begin firing wildly in every direction. Perry, fearing that they will shoot each other, yells to them to row to shore.

Scott echoes the order. The big colonel has planned carefully for this moment. Captured at Queenston and exchanged after months as a prisoner in Quebec, he has no intention of letting a less experienced officer bungle the landing. When Dearborn made him

adjutant-general, Scott insisted on retaining command of his 2nd Artillery Regiment, insisted also on commanding the assault wave.

He is in charge of twenty boats containing eight hundred men and a three-pounder cannon. His orders are specific: advance three hundred paces only across the beach toward the high bank, then wait for the first wave of infantry—fifteen hundred troops under Brigadier-General John Boyd, a one-time soldier of fortune with a long service in India.

Into the water go Scott’s men, through the spray and onto the sand, forming swiftly into line, cannon on the left. As they dash for the bank, the next wave approaches the beach in such a torrent of musketry that Boyd sees the entire surface of the water turn to foam; he himself will count three musket balls in his cloak.

As Boyd’s men hit the beach, some of Scott’s assault force have already reached the crest of the twelve-foot clay bank. The British and Canadian militia, bursting out of the shelter of a ravine two hundred yards away, hurl them back down the cliff. Scott—a gigantic figure, six feet five inches tall—is unmistakable. One of the Glengarries attacks him with a bayonet. Scott dodges, loses his footing, tumbles back down the bank.

On board

Madison

, Dearborn sees his adjutant-general fall and utters an agonizing cry:

“He is lost! He is killed!”

But Scott has already picked himself up and is leading a second charge up the bank.

The schooners have slackened their covering fire for fear of hitting their own men. Perry, realizing this, pulls over to

Hamilton

and directs its nine guns to pour grape and canister onto the crest. The British retreat to the cover of the ravine, where more troops are forming. Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Myers, Vincent’s acting quartermaster general, now leads a second attack on the men clawing their way up the bank. Once again Scott is forced back.

A scene of singular carnage follows. Two lines of men face each other at a distance of no more than ten yards and for the next fifteen minutes fire away at point-blank range. On the British side, every

field officer and most junior officers are casualties. Myers falls early, bleeding from three wounds. The British, fighting against odds of four to one, are forced back, leaving more than one hundred corpses piled on the bank. An American surgeon, James Mann, who lands after the battle is over, counts four hundred dead and wounded men, strewn over a plot no longer than two hundred yards, no broader than fifteen.

Lieutenant-Colonel John Harvey, Vincent’s deputy adjutant-general who has arrived with reinforcements, now steps into the wounded Myers’s command and leads his shattered force in a stubborn retreat from ravine to ravine back toward the little town of Newark, scarred by shellfire and totally deserted.

Chauncey, meanwhile, has brought his flagship,

Madison

, into the river opposite the British fort. At the same time comes news of another American column massing at Youngstown farther upriver, apparently intent on crossing and cutting off the British retreat. As more troops land on the beach, the Americans form into three columns with the riflemen and light infantry flitting through the woods on the right to get past Harvey’s forces and threaten his rear.

Vincent realizes that nothing can save the fort. Tears glisten in his eyes as he dispatches a one-sentence note to Colonel William Claus of the Indian Department, in charge of the garrison, ordering him to blow up the magazine, evacuate the fort, and join the retreating army on the Queenston road.

At the fort, Colonel Claus orders his men to leave, sets several long fuses on the three magazines, tries to chop down the flagpole to retrieve the Union Jack. The axe is blunt, the work only half done when the American advance troops are heard outside the fort. Claus drops his axe, makes a hurried escape.

The American columns move cautiously on the fort, their advance rendered ponderous by the lack of draught animals: the heavy artillery must be manhandled. Winfield Scott, impatient to pursue the British, seizes the riderless horse of the wounded Myers and dashes off at the head of his skirmishers, galloping down the empty streets of Newark and on to the fort, half a mile beyond, in time to capture

two British stragglers. From them he learns that the guns are spiked, the magazines about to blow.

Off he gallops, trying to save the ammunition. He is under the wall of the fort when the main magazine goes up, hurling a cloud of debris into the air. A piece of timber falls on Scott, throwing him from his horse, breaking his collarbone. Two officers pull him to his feet and he presses on, forces the gate, stamps out the lighted train leading to the smaller magazines. Then he turns his attention to the flagstaff, partly cut through by Claus. In spite of his injury, he topples it with the blunt axe, claims the flag as a souvenir.

In dashes Moses Porter, the artillery colonel, who has also spotted the British standard flying and wants it for himself.

“Damn you, Scott!” he cries. “Those cursed long legs of yours have got you here ahead of me.”

Meanwhile Vincent and his division are retreating swiftly and silently toward the village of St. Davids, the infantry retiring through the woods, the artillery and baggage along the road. Their ultimate goal is Burlington Heights at the head of the lake. The Americans are in danger of winning another hollow victory, and Scott knows it. Painfully, he hoists his big frame back onto his injured horse and gallops off once more in the wake of his own light troops who are already picking up stragglers from the British column.

The original American plan called for Colonel James Burn and his dragoons to cross the river from Youngstown to cut off the British retreat, but this attack has been delayed by the threatening fire of a British battery. Now, with the whole of the Niagara frontier being evacuated, Burn is able at last to land his fresh troops within musket shot of the enemy stragglers.

When he arrives on the Canadian shore, Burn asks Scott to wait fifteen minutes while he forms up his men; then their combined forces can proceed to harry the British retreat.

It is a fatal delay, for neither officer has reckoned on the timidity of the high command. Dearborn, who can scarcely stand and has to be helped about by two men, is incapable of decision; he will claim afterwards that the troops were too exhausted to engage in pursuit,

ignoring all evidence that Burn’s dragoons are fresh and Scott’s skirmishers eager for the fray. Dearborn has turned direct command over to Major-General Morgan Lewis, who finally lands after the battle on the beach is over. Lewis is a politician, not a soldier, a former chief justice and governor of New York State, a brother-in-law of the Secretary of War, and a boyhood friend of the President. He loves playing at commander, revels in pomp and ceremony, and once, in a memorable speech to the New York militia, made a remark that has become a persistent source of ridicule: the drum, General Lewis purports to believe, is “all important in the day of battle.”

Lewis is terrified of making a mistake—a bad quality in a commanding officer. He remembers the follies of overconfidence that destroyed Van Rensselaer’s army at Queenston and Winchester’s at Frenchtown the previous year and decides to play it safe.

He sends two messengers forward to restrain Scott from any further advance. Scott disregards the order.

“Your general does not know that I have the enemy within my power,” he tells them. “In seventy minutes I shall bag their whole force, now the dragoons are with me.”

But, as Scott waits for the rest of Burn’s boats to land, Brigadier-General Boyd himself rides up and gives him a direct order to withdraw to Fort George. Disgusted, Scott abandons his plans. He can see the rearguard of Vincent’s army disappearing into the woods. The defeated columns are marching off in perfect order, with much of their equipment intact, a circumstance that lessens the American triumph. Once again the invaders have cracked the shell of the nut but lost the kernel. Trapped all year in the enclave of Fort George, unable to break out for long because of Vincent’s raiders lurking on the outskirts, an entire American army will be reduced to illness, idleness, and frustration.

Scott controls his disgust. In spite of a natural impulsiveness, he has learned to curb his tongue in the interests of his career, for he is nothing if not ambitious. But he cannot forgive Boyd, the man who ordered him back to Fort George just as he was about to destroy an army.

In Scott’s later assessment, this blustering soldier of fortune is serviceable enough in a subordinate position but “vacillating and imbecile beyond all endurance as a chief under high responsibilities.” Notwithstanding this harsh appraisal, Boyd is soon to take charge of all the American forces occupying the Niagara frontier.

Dearborn’s immediate inclination is to move his troops to the head of the lake by water and cut off the British retreat. For that venture he needs the enthusiastic co-operation of the fleet and its commodore, Isaac Chauncey. That is not forthcoming. Chauncey, at forty-one, has gone to flesh—a pear-shaped figure with a pear-shaped head, double-chinned and sleepy-eyed. The navy has been his life. He earned his reputation during the attack on Tripoli in 1804 but is better known as a consummate organizer. In command on both lakes, he is really concerned with Ontario, where he is determined to achieve naval superiority. This obsesses him to the exclusion of all else. His task, as he sees it, is to build as many ships as possible, to preserve them from attack, and to destroy the enemy’s fleet. But his fear of losing a contest—and thus losing the lake—makes him wary and overcautious. Chauncey will not dare; before he will attack his adversary’s flotilla everything must be right: wind, weather, naval superiority. But, since nothing can ever be quite right for Chauncey, this war will be a series of frustrations in which he, and his equally cautious opposite number, Sir James Yeo, flit about the lake avoiding decisive action, fleeing as much from their own irresolution as from the opposing guns, always waiting for the right moment, which never comes.