Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (4 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

“The Philadelphia of To-Day: The World's Greatest Workshop” (1908), showing the entire central waterfront.

Author's collection

.

The curvilinear Willow Street was built on top of the sewer by 1829. The Northern Liberties and Penn Township Railroad (aka the Delaware and Schuylkill Railroad and the Willow Street Railroad) laid tracks on the surface in 1834. These tracks ran westward from the Willow Street Wharf on the Delaware and connected to the tracks of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad on Pennsylvania Avenue west of Broad Street.

In the 1850s, the line became part of the Reading Railroad. The Reading also incorporated the freight houses of the North Pennsylvania Railroad, then located on Front Street between Noble and Willow.

The railroad tracks on Willow Street were removed in the late 1960s as part of the East Callowhill Urban Renewal Area. Hundreds of houses and commercial establishments were torn down in this misguided city planning project that sought to create open space for industrial use. By necessity, the sewer under Willow Street had to remain, which is why Willow Street itself was not eliminated when other streets in the project area were. The sewer still flows to the Delaware at Pier 25, under Cavanaugh's River Deck. Willow Street no longer makes it to Delaware Avenue due to Highway 95.

C

URVY

W

OMEN AND

C

ROOKED

M

EN BY THE

D

ELAWARE

This locale was also Philadelphia's first red-light district. Prostitutes frequented its hostels and boardinghouses, and drinkers gathered at any number of seedy taverns. There were also ramshackle shops and street vendors who sold exotic goods taken to them by sailors from ships arriving from all over the world. This commotion attracted a diverse group of peopleâcommon laborers, privateers, sailors, gamblers and swindlers of all types.

The area became a center for revelers from Philadelphia and Northern Liberties looking for adventure away from the eyes of authorities. This is because the neighborhoodâpart of the Northern Liberties District but not Northern Liberties Townshipâwas not fully represented by a municipal government or regularly patrolled by constables until it became part of Philadelphia in 1854. It was that year that the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania combined Northern Liberties and other districts and townships in Philadelphia County into the City of Philadelphia under the Act of Consolidation (P.L. 21, No. 16).

The North End was thus Philadelphia's first “outlaw” district and had a history of violence in the eighteenth century. For instance, Gallow's Hill near Front and Callowhill was the site of a number of public hangings. John Fanning Watson, in his

Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania

, reminisces: “In my youthful days Callowhill street was often called âGallows-hill street.'”

The following quote from

Philadelphia and Its Environs: A Guide to the City and Surroundings

(1893) suggests how poorly regarded these parts were by the 1890s and how many people lived and worked in the vicinity:

The river-front, northward from the Willow Street freight-yards, is a scene of almost perpetual business movement upon a large scale. Commercial and manufacturing enterprise has here one of its busiest seats. It is not an attractive quarter of the city in its aspect to the stranger, but thousands of wage-earners here obtain subsistence for their families. Great factories seem to be elbowed by lofty warehouses; extensive lumber-yards are flanked by rolling-mills and foundries; and in many of the poorer streets, too often ill-kept and mean, there are battered and weather-worn, old frame houses, and dingy rows of old-fashioned, low, brick dwellings

.

T

HE

W

ILLOW AND

N

OBLE

S

TREETS

G

ROUP AND

Y

ARDS

The Reading Railroad owned Piers 24, 25 and 27 North, a group of covered finger piers at the bottom of Noble and Willow Streets. The Willow and Noble Streets Group, as it was called, was the second busiest general freight-handling station on the Reading system. These were strictly import piers; the Reading's local export piers were at Port Richmond, a few miles north. Piers 24, 25 and 27 could process sixty-five rail cars of cargo a day, and about five hundred men worked on them in the early 1900s.

The Reading also leased these piers: Pier 24 to the Allan Steamship Company, which operated steamers for freight and passenger traffic between Philadelphia and St. Johns, Halifax, Glasgow and Liverpool; Pier 25 to the Philadelphia Transatlantic Line and the Bull Line, both of which ran steamers for freight to London and Scotland; and Pier 27 to the Holland America and the Scandinavian lines for shipping freight to Rotterdam and Copenhagen.

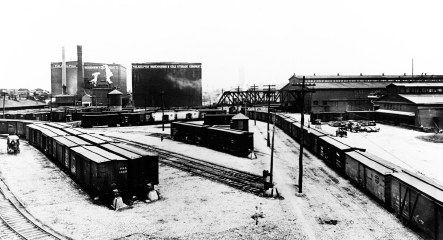

The Willow and Noble Streets Group worked in conjunction with the Willow and Noble Streets Station on the west side of Delaware Avenue. This was a major railroad freight yard in its day, and a great deal of freight traffic between Philadelphia and New York was exchanged at this point. It's almost certain that the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia exported hundreds of steam engines to countries on all continents from this terminal. This harkens back to when Philadelphia was the “Workshop of the World.”

Freight movement diminished in the 1950s and ended by the 1970s. A fire destroyed Pier 27 in the morning of August 31, 1972. Firefighters, some on fireboats, worked hard to prevent the blaze from spreading to Piers 25 and 24. They succeeded, but Pier 24 itself burned less than a year later. A dazzling inferno ripped though it on July 7, 1973, leaving the place fully leveled. Arson was suspected in both cases.

Reading Railroad's Willow and Noble Streets Freight Yard in 1914. Piers 24, 25 and 27 North are on the right. Willow Street is out of the picture on the left. The Philadelphia Cold Storage buildings are in the background.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

Today, Piers 24 and 27 are parking lots, while Cavanaugh's River Deck is on Pier 25. The Reading Railroad's one-time rail yard is now a land bank currently hosting a self-storage firm. This property has long been touted as the future location of the World Trade Center of Greater Philadelphia. Plans include three office buildings devoted to maritime trade and a residential tower. The goal of this fanciful project is to make Philadelphia one of the one hundred cities in the World Trade Centers Association with a major World Trade Center.

T

HE

T

OWN OF

C

ALLOWHILL

Callowhill Street is unusually wide as it approaches the Delaware River because several market sheds were located in the middle of and alongside the avenue in the mid-1700s. A town called Callowhill grew up around this shopping district, having been platted by Thomas Penn, one of William Penn's sons.

Penn's descendants owned much of the land in the Northern Liberties District north of Vine Street, and they routinely sold off lots to generate income. So, about 1768â70, Thomas Penn laid out a northâsouth lane, New Market Street, between Front and Second and then dedicated four pieces of ground for a public market at each corner of the intersection with Callowhill Street. This became the center of the new town of Callowhill.

Quakers who wanted to get away from the swarming town of Philadelphia moved to Callowhill. It accordingly prospered as the city's most immediate northern suburb. The community remained a food distribution hub and a residential area well after being subsumed into the city of Philadelphia.

Even in the 1950s, when the neighborhood was shabby, Callowhill was still an active meat and produce center. But it was, by then, part of Philadelphia's Skid Row district, a place replete with cheap flophouses, grubby bars, dilapidated warehouses and so on.

When Interstate 95 plowed through this quarter, it completely obliterated what had once been Callowhill. The bustling town, centered at the intersection that William Penn's son established, was located exactly where Callowhill Street dips under the multilane freeway. Today, not even the shadow of a trace of the town of Callowhill exists.

4

C

ALLOWHILL TO

V

INE

P

ENN

'

S

S

URVIVING

S

TEPS AND

S

HIPS AND

F

ERRIES ON THE

F

ROZEN

D

ELAWARE

Callowhill Street was first called “the new street” since it was the first road opened in Northern Liberties, north of Philadelphia's original northern limit. This was in 1690. William Penn later renamed the street after his second wife, Hannah Callowhill (1671â1726), apparently during his second stay in America (1701â02).

T

HE

W

OOD

S

TREET

S

TEPS

The steps at 323 North Front Street are usually referred to as the Wood Street Steps. This staircase consists of fourteen granite blocks, including twelve treads and two landing areas. They are the last set of William Penn's public stairs along the Philadelphia bank of the Delaware River to survive.

That they do survive is a miracle of sorts. As late as the 1980s, the Wood Street Steps were in jeopardy. An adjoining owner wanted the city to strike the passageway from the street plan so that he could acquire the ground to enlarge his property. The River's Edge Civic Association, a local civic group, put a stop to that plan.

The stairway was once an extension of a slender alley between Vine and Callowhill called Wood Street. The steps were built between 1702 and 1737, but while the treads originally could have been wooden, there's some evidence that the granite steps there today may date from the late seventeenth century. The stone treads were there for sure in 1737, when Wood Street was first registered as a public street.

The Wood Street Steps today.

Photo by the author

.

The ten-foot-wide passageway between 321 and 325 North Frontâand between 322 and 324 North Waterâis still labeled as Wood in city records and is administered by the Philadelphia Department of Streets. The Wood Street Steps were certified by the city's Historical Commission in 1986 and are listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

A land warrant (patent) by William Penn to one Henry Johnson in March 1689 actually established the Wood Street Steps. Johnson was the buyer of forty feet of ground on the east side of Front Street north of Vine. A provision reads:

[T]

he said Henry Johnson his Heirs and Assigns shall further leave a Proportionable Part of the said Lot for Building one publick Pair of Stone Stairs of ten Foot in Bredth leading from the said Front Street down to the said Lower Street or Cartway and so forward to the Wharfs And one Pair of Stone Stairs from off the Wharfs down to Low Water Mark of the said River in the Middle or most convenient place between Vine Street and the North Bridge

.

This passage substantiates the authorization of stone steps back to William Penn himself, although it doesn't prove if and when any steps were built. It also indicates that the Wood Street Steps were initially meant to be made of stone. Local historians have generally thought that this and other bank stairs were made of wood until the 1720s or 1730s, at which time granite steps were installed. The warrant shows that Penn wanted stone rather than wooden steps and makes it more likely that the existing Wood Street Steps were built prior to earlier estimated dates, though this cannot be proven.

The warrant also directs that the riverbank stairs between Vine and Callowhill were to extend down into the Delaware River at low tide on the east side of Water Street (the “Lower Street” or “Cartway”). It's unclear if these particular steps ever reached into the Delaware, but other bank stairways did continue on the east side of Water Street as walkways with additional stairs that descended straight into the river for use at low tide. (Yes, the Delaware is a tidal waterway, rising and falling about six feet twice a day.)