Pericles of Athens (5 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

In roughly the same period, Pausanias adopted a radically opposed view in his

Periegesis

, in a passage in which he digressed on the subject of the famous men of the Athenian

past. While happy to praise the military exploits of Themistocles, Xanthippus, and

Cimon against the Persians (8.52.1–2), he expresses the greatest scorn for the warmongers

of the Peloponnesian conflict, “especially the most distinguished of them.” His judgment

is categorical: “they might be said to be murderers, almost wreckers of Greece.”

28

Scandalized by the Greek internal wars, Pausanias does not deign even to mention

the name of Pericles and assigns him to a kind of

damnatio memoriae

.

Without any clear suggestion of a cause-and-effect link, the memory of the

stratēgos

thereafter progressively continued to fade right down to the early

fifteenth century, at which point the humanist Leonardo Bruni, inspired by the writings

of Thucydides and Aelius Aristides, revived it.

29

From this rapid survey of the sources of Antiquity, it is possible to draw two clear

conclusions. The first is somewhat disappointing: to produce a straightforward biography

of Pericles involves guesswork or even an illusion, unless one imitates Plutarch and

creates an imaginary itinerary that reveals more about the preconceptions of its creator

than it does about the trajectory of the

stratēgos

. For what can be said about Pericles’ youth prior to 472, the date when he financed

Aeschylus’s

Persians

? What do we really know of his life between 461 and 450? No linear account of the

stratēgos

’s life is conceivable—unless, that is, one cheats with the information provided and

arranges it into a chronological order that, although coherent, is arbitrary. Only

the last three years of his existence, from 432 to 429, rise to the surface in this

ocean of ignorance, and they do so thanks to the unique shaft of light shed by Thucydides’

Peloponnesian War

.

Does this amount to an insurmountable defect that rules out writing any book about

Pericles? Not at all. A perusal of the ancient sources in fact indicates another,

surely more fruitful avenue of research. The ancient sources, ranging from Thucydides

to Plutarch and from the comic poets to Aelius Aristides, all, in their own ways,

ponder the relations established between Pericles the individual and the community

in which he lived. Is Pericles an all-powerful figure or simply a ventriloquist who

expresses the aspirations of the people? A wide range of answers can be envisaged,

and they deserve to be closely scrutinized. And this is the line of investigation

that will serve as a guiding thread for the present inquiry, which will be organized

into two major parts, the one historical, the other historiographical.

The first section will start with a study of the genealogical, economic, and cultural

trump cards that were held by the young Pericles at the point when he stealthily embarked

upon his political career (

chapter 1

). The following two chapters will be devoted to the bases of Pericles’ power. These

were clearly twofold: his success rested on military glory—as head of the Athenian

armies and navies (

chapter 2

)—and on his expert handling of public discourse—to the point of embodying the orator

par excellence who fascinated the Athenians from the Assembly tribune (

chapter 3

).

As

stratēgos

, Pericles was deeply implicated in the development of Athenian imperialism. With

no misgivings at all, he ruthlessly crushed the revolts of the allied cities, adopting

in this respect a policy that was widely favored in Athens: possibly his sole originality

lay in his theorizing its necessity and establishing imperial power on an unprecedented

scale (

chapter 4

). Within the city, Pericles actively promoted the genesis of a truly democratic economic

policy—a policy that was founded on widespread redistributions of the city’s wealth

to a newly redefined civic community (

chapter 5

).

Both within the city and beyond it, Pericles responded to the demands of the people

or even anticipated them. The pressure that the

dēmos

exerted could be felt at every level. It was because the least of his actions and

gestures were all scrutinized and, frequently, criticized that Pericles seems to have

kept his relatives, friends, and lovers at a distance. He no doubt hoped in this way

to ward off the many attackers who described him as a man who was manipulated, ready

to put the interests of those close to him before the well-being of the Athenian people

(

chapters 6

and

7

). Such reproaches were likewise leveled against his attitude toward the city gods,

for he was also accused of fostering friendships with impious men (

chapter 8

).

At Pericles’ death, these weighty suspicions faded away: the

stratēgos

now, a least for a part of tradition, came to symbolize a golden age that was gone

forever. A number of ancient authors even treated the passing of Pericles as a pivotal

moment in the history of Athens, as if his death marked the starting point of the

city’s decadence—a view that calls for serious qualification (

chapter 9

).

Having completed this historical journey, it will be necessary to reconsider this

whole investigation and return to the question formulated right at the outset—namely,

how did the Athenian democracy react to its experience of this great man? In short,

we must try to understand Athens as a reflection of Pericles and Pericles as a reflection

of Athens (

chapter 10

).

Pericles was neither a hero nor a nobody. He should be restored to his full complexity,

and we should endeavor to free ourselves from a historiography that, over a long period,

either ignored him or exposed him to public contempt, before eventually transforming

him into a veritable icon of democracy. The Periclean myth is a recent re-creation.

Up until the end of the eighteenth century, Pericles was for the most part judged

with disdain, if not arrogantly ignored. Blinded by Roman and Spartan models, the

men of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment regarded the

stratēgos

as an unscrupulous demagogue who headed a degenerate regime (

chapter 11

). It was not until the nineteenth century—and, in particular, Thucydides’ return

to favor—coupled with the advent of parliamentary regimes in Europe—that, progressively,

a new Pericles emerged in the writings of historians, where he was now presented as

an enlightened bourgeois. Prepared by Rollin and Voltaire and completed by George

Grote and Victor Duruy, this slow metamorphosis engendered the figure of an idealized

Pericles who, still today, is enthroned in school textbooks on a par with Louis XIV

(

chapter 12

).

CHAPTER 1

An Ordinary Young Athenian Aristocrat?

I

n the

Politics

, Aristotle defines the elite by a collection of characteristics that distinguishes

it from the common people: good birth (

eugeneia

), wealth (

ploutos

), excellence (

aretē

), and, finally, education (

paideia

).

1

These were the various aspects, combined in different degrees, that defined social

superiority in the Greek world. Pericles was clearly abundantly endowed with all those

distinctive attributes. However, in a democratic context, such advantages could sometimes

turn out to operate as obstacles or even handicaps. Not all forms of superiority were

acceptable in themselves, but needed to adopt a form that was tolerated by the

dēmos

for fear of arousing its mistrust or even anger: in Athens, the forms taken by distinction

constituted an object of implicit negotiation between members of the elite and the

people.

Such compromises were evident at every level. Membership of a prestigious lineage

was undeniably an advantage, provided that the people did not doubt the family’s attachment

to the new regime that Cleisthenes had set in place. Likewise, wealth was a blessing

for anyone who wished to launch himself into political life, but only if that fortune

was judged to be legitimate by the Athenians and if a considerable proportion of those

riches was used to benefit the community as a whole. Finally, the asset of a refined

education was of capital importance in a context in which influence was clearly associated

with an ability to hold forth in the Assembly; but if that skill was employed in a

thoughtless manner it could be taken for a form of cultural arrogance that the average

citizen would not tolerate.

Pericles’ entrance upon the Athenian political stage took place in the context of

this generalized negotiation. His first dextrous steps into public life enabled him

to win over the people by demonstrating that his superiority, at once genealogical,

economic, and also cultural, was compatible with the democratic ideology and the practices

that were taking shape.

T

HE

T

RUMP

C

ARDS

H

ELD BY THE

Y

OUNG

P

ERICLES

Eugeneia

: An Equivocal Ancestry

At the time of Pericles’ birth, strictly speaking, there was in Athens no “aristocracy”

in the sense of a system in which hereditary power was held by a few great families.

Yet for a long time historians believed that in the Archaic period, the city was managed

by a handful of lineages that monopolized all powers. In truth, however, that is a

mistaken interpretation of the ancient sources, read through the deforming prism of

ancient Rome. The city of Athens was, quite simply, not organized into

genē

. In the Archaic and the Classical periods,

genē

essentially designated families—or groups of families—from which the priest or priestess

of a civic cult was chosen; and no more than a marginal political influence seems

to have been exerted by those groups.

2

However, this does not mean that descent counted for nothing in early-fifth-century

Athens. There were undoubtedly certain powerful families (

oikiai

) that played a primary role in city life. All Athenians belonged to lineages that

it is possible to pick out thanks to the names borne by their members. Pericles was

called “the son of Xanthippus,” and his eldest son was called “Xanthippus, son of

Pericles.” The rules for passing a name down resulted in the eldest son acquiring

the name of his paternal grandfather, thereby creating an interplay of recognizable

echoes and conferring a cumulative aura upon patronyms. Pericles, the younger son

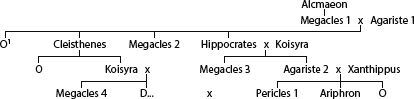

of Xanthippus and Agariste, in point of fact came from a doubly prestigious line (

figure 1

), but was not a member of any kind of “nobility,” in the sense that the word still

carries today.

His father Xanthippus, son of Ariphron, led the Athenian and other Greek troops to

victory in the battle of Cape Mycale, at the end of the Second Persian War. The author

of the

Constitution of the Athenians

even calls him the “people’s champion” (

prostatēs tou dēmou

),

3

and his influence was considered sufficiently alarming for him to be ostracized by

the Athenians in 485 B.C. However, contrary to one deeply rooted historiographical

myth, he

did not belong to the postulated

genos

of the Bouzygae:

4

neither Herodotus nor Thucydides nor even Plutarch have anything to say about this.

In reality, the belief rests upon a mistaken reading of a fragment from a comic poet,

Eupolis, who had one of his characters declare: “Is there any orator that can be cited

now? The best is the Bouzyges, the cursed one [

alitērios

]!”

5

But, according to one ancient commentator, the poet, far from alluding to Pericles,

was referring to a certain Demostratus, an orator who played a by no means negligible

role in Athens at the time of the Peloponnesian War.

6

FIGURE 1.

Pericles’ genealogical tree.

In truth, little is known about Xanthippus’s clan except that its lineage was judged

sufficiently prestigious for the Alcmaeonids to consent to give it one of their daughters

in marriage (Herodotus, 6.131). So initially, it was actually through his maternal

descent that Pericles came to the city’s notice.

7

The Alcmaeonids were certainly one of the most illustrious Athenian clans, but they

did not constitute a

genos

since no hereditary priesthood was associated with them. All the same, theirs was

a powerful

oikos

(the term used by Herodotus, 6.125.5), and that was no small matter. Their influence

was already evident even before the establishment of Pisistratus’s tyranny in 561

B.C. According to tradition, Alcmaeon, the eponymous ancestor of the lineage, was

the first Athenian to win the chariot race at Olympia,

8

thereby shedding glory upon his entire lineage. Then, a few years before Pericles’

birth—in 508/7 B.C.—another Alcmaeonid, Cleisthenes, initiated a thorough reform of

the civic organization, thereby establishing the bases of the future democratic system.

And it was Agariste, the niece of Cleisthenes the lawgiver, who married Xanthippus

and gave birth to Pericles.

9