Read Midnight and the Meaning of Love Online

Authors: Sister Souljah

Midnight and the Meaning of Love (35 page)

“Come this way,” Chiasa said.

The fact that it was wider than any indoor fighting/training space I had ever seen was not even its strongest point. The floor was made

of bamboo laid in perfectly for the length of a football field. It was so clean, flawless, and polished, that it seemed impossible to imagine that anyone had ever placed a foot on it. The ceilings were forty-eight feet high. I pretended to myself that this was in case a fighter wanted to fly. The ceiling too was designed with great care and precision. Like a complicated math problem, a craftsman had cut the entire ceiling into even squares and surrounded more than two hundred squares with bamboo borders to outline and highlight its perfection. Some of the squares were lit up brightly, which the floors reflected, the light giving everyone the opportunity to see every movement that any fighter might make. Even in the hallways the floors were incredible, the wooden seats placed at even distances and immovable, so that no one could alter the order and the measurement and the count—or the seating arrangement.

The female fighters in Chiasa’s class sat on their knees. Their silence and their form was elegant, their uniforms flowing with the contour of their bodies. Not tight, not too loose. To the left of each was a face helmet, a type that I had never seen but admired. The male fighters sat across the room, their robes as expertly tied, tidy and neat. The elder men sat at a table, which of course raised them above the heads of both their male and female students, who all sat with their swords to the side.

At first I believed a sensei would take charge and begin to lead the class. On second thought it seemed the presence of the elders signaled some kind of ceremony or ritual. Because I couldn’t understand the language, I watched it like a video with the volume dropped out. This made my eyes pay even closer attention to each detail.

An elder laid out several medals on the head table.

An awards ceremony

, I guessed.

Suddenly Chiasa stood up, held her helmet at one side and sword at the other. She approached one of the elders and bowed before him. The elder man spoke softly to her and at length. Chiasa was completely subdued, silent, and humbled. At his last words he lifted a gold medal with a red ribbon on it and placed it around her lowered head. She in turn did a deep bow before him. Quietly she turned, her eyes seeming to survey the room. Then she walked over to another seated female fighter. She stood before her, then slowly put on her helmet. She tied its long strings back, her fingers moving expertly behind her head as though she had easily tied it a thousand times. With the helmet secured and in her full uniform, she looked completely different and more incredible to me. She raised her sword and lowered it at the head of the seated girl. Without notice, all the other seated fighters slid either to the left or the right and stilled once again on their knees, now all facing the girl who was left seated alone.

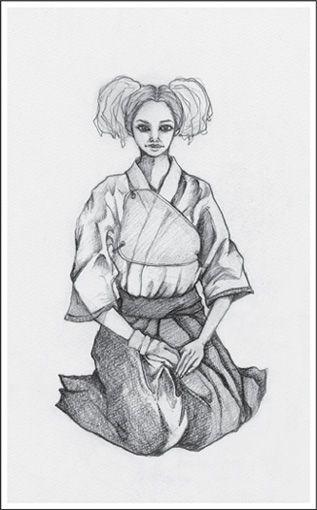

Chiasa wearing her kendo dogi.

Slowly the girl stood up. She picked up her helmet. Before she covered her head, I realized that it was Yuka, the girl from the plane who had introduced herself to me univited by simply saying, “Let’s trade music.” I leaned forward on the wooden bleachers where I was seated and watched intently.

The tremble of Yuka’s finger was so slight it could’ve been missed. She tied her helmet and raised her sword. It seemed to signal that she had accepted the challenge.

Chiasa crashed Yuka’s head with the sword with a dizzying speed. It woke Yuka up and their battle began. The bamboo sword striking both the metal helmet and the thick

dogi

made loud crashes. Yet even louder were the warlike cries and shouts of Chiasa as she set to conquer and humiliate her opponent on the dojo floor.

The style of fighting was unusual to me. The helmet offered too much protection, I thought. The fight was waged with the upper body and not the feet. Although their feet moved in a rhythmic dance. From the strike of the sword, I could calculate that they were both aiming only at the head, the throat, the stomach, and the wrists.

The elders were transfixed and absorbed by the battle. Even I was completely drawn in. It seemed that men battle one another individually and in groups, gangs, and armies all across the globe, yet warring women mesmerized us all. No longer seated, the elders were each standing on their feet with their arms folded before them. Their eyeballs bounced and jumped at each movement the girl fighters made.

Chiasa’s style was unforgiving. When her and Yuka’s raised swords met, she stepped in even closer and thrust Yuka backward. Yuka was propelled by the push but caught herself from falling. She was lighter than Chiasa, although both of them were slim. Yuka danced forward again, her feet moving in a calculated rhythm. She raised her sword to strike Chiasa. Chiasa blocked her sword and moved out of the block faster than Yuka, striking both of Yuka’s wrists in two sharp blows.

An elder gasped. Yuka was hurt. One sensei yelled out something in Japanese. Yuka raised her sword again. Her two hands tight on the sword grip, she charged Chiasa, but Chiasa altered her approach and didn’t advance. Chiasa lowered her sword some as Yuka advanced and lunged it into Yuka’s throat, and all the elders stepped in, calling out commands in Japanese. They each raised one hand, which caused the sparring to cease and acknowledged Chiasa had won.

The match was finished now. The girls still faced one another, holding their form. In a precise movement the girls raised their swords so that they touched. Then they dropped their swords at their waist and both took five steps backward. They both took a deep bow acknowledging each other, both saying,

“Arigato gozaimasu.”

The politeness seemed important to the Japanese—even in the most heated and hateful exchanges. I was certain that I was not the only one who could feel that the fight between Yuka and Chiasa was more than just a practice or training exercise. It felt intense and personal. It felt deadly.

Yuka returned to her original position on the floor and Chiasa remained standing. The fellow fighters applauded her now. When the helmets were off and the quiet resumed, Chiasa spoke out some words in Japanese to Yuka. Yuka’s facial expression tightened. The elder spoke some words to Yuka, and it seemed whatever they had been debating was solved. Chiasa bowed again to the elder. Their bowing seemed endless. One bow led to another.

Soon Chiasa left the room. I stood up from the top bleacher where I was positioned. Yuka’s eyes connected with mine. Her face softened and filled with both surprise and delight. In the one second that it takes for a thought to occur, Yuka snatched back her warm expression and glared at me with the look of having been betrayed. I walked out to meet Chiasa wherever she had gone to. It didn’t matter. I knew from the way they were swinging the swords at each other that I had to choose between them—and of course, easily, I had chosen Chiasa.

Leaning against the wall opposite the women’s locker room, I waited for her. Twenty minutes passed by before I began to search around. Back in the main dojo, I stuck my head in. She wasn’t there. Yet as all the fighters began to file out to the locker rooms, Yuka was on her knees, a cloth in her hand, wiping the floor. She was cleaning

the cleanest and largest dojo floor I had ever seen. The elder who had spoken Japanese to her in a hardened tone was the only adult remaining. I closed the door. I had opened six doors before I located Chiasa behind the seventh. She wore now a black

dogi

and had donned a red belt, no helmet, no skirt, no sword. My entrance didn’t break her concentration as she fought a girl wearing a black belt. Her sensei stood almost inside the fighting circle as though he was part of the match or maybe he was a caution sign. Their fight ended seconds after my arrival. I wish I had seen it. I sat on an empty bench.

Just as I believed that she was done for the night, I stood up. As I did, a Japanese youth stood also. He wore a black belt. As I watched, he and Chiasa bowed before one another and struck a stance.

“Chiasa,” I called her out. The sensei, the fighters, and the guy she was about to fight all shifted their eyes to my direction. Chiasa did not. She kept her eyes on her opponent. Her sensei said something to her. Chiasa answered him back in Japanese. The sensei spoke again and then she spoke again. Her opponent said some words, and then Chiasa said to me, “Come on, are you ready to fight? My opponent has yielded to you.” The sensei watched me intensely, his blank face no longer reading caution. Now he was a green light and behind it was curiosity, anticipation, and fear of the unknown that I could sense and see. I had only called out to Chiasa because I didn’t want her fighting a male fighter. I couldn’t sit by and watch it for sport. Now she wanted to fight me instead of him. No problem, at least I knew I wouldn’t strike or hurt her.

My army-green Girbauds were loose-fitting enough. My shoes were already off. I approached. We were both supposed to bow. She bowed. We both struck our stances. I recognized her perfect form—yet somehow it was entertainment to me. She showed me that it was not entertainment for her. Serious-faced, she angled left and made the first strike with her right foot followed by her right hand. I blocked both. She pulled back and moved both her feet and her eyes around looking for a

suki

. I could tell she wanted me to make a move. I didn’t, just watched her, moved my feet around but held my hands in a defensive position. She lunged forward striking out again with her right hand. When I moved to block she moved her left leg like lightning and kneed me in my stomach. I held her right fist and twisted it and brought it behind her body to immobilize her. Purposely, my grip was

not strong or tight. She used her left elbow, a reverse move to strike me strategically against the left side of my jaw. I felt that. She had caught me off guard. I jumped back and looked at her then smiled. She took my smile as an insult, ran up on me, and leaped off the floor into a double flying kick. Instead of blocking, resisting, or striking, I sidestepped and snatched up her body from midair. I threw her over my shoulder then spun her around like a five year old to confuse her vision. I set her down on her feet. As she steadied herself, I took full advantage. Within three seconds I folded Chiasa up and carried her out of the dojo in my arms with zero protest from her sensei and the fighters who she had been intimidating all night. As I moved swiftly past the passive observers with their female champion, no sword-swinging samurais or silent ninja assassins or karate killers emerged to defend her honor.

I put her down on the ground outside the dojo. Then I sat down beside her. She smiled at me. Naturally, I smiled at her. I loved her spirit. All fire.

“See, now you respect me,” she said, slowing down her breathing. “And I respect you more,” she added. “Two people can spend weeks together and never develop the respect that two fighters can earn in one match. I know that guys don’t respect girls too much. So I fight to let them know I am Chiasa, a whole woman, not half a person. Treat me right.”

As we walked back through Yoyogi, all the lampposts switched off. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I was reminded of the complete blackness that enveloped my grandfather’s Southern Sudanese village—when the moon and the stars went on break, as they sometimes do.

I could smell the scent of pine trees and of the cypress and zelkova and oak all intermingling.

“I do respect you, Chiasa,” I admitted.

“Arigato gozaimasu,”

she replied softly without bowing down. I was grateful.

The cicada sang as we moved in silence. I thought about how she was training in so many different fighting styles—kendo,

kyudo

, and karate. She must have some reason pushing her.

“Chiasa, which style of fight is your favorite?” I asked.

“I’m bored with it all. I don’t want the bamboo practice sword. I

prefer the blade,” she said softly. I don’t want to aim at a stable bullseye, I want to fire on a live moving target.”

“The real thing would kill your opponent,” I cautioned her.

“As long as we both knew that before we fight, that’s fair and square,” she said without laughter.

* * *

I left Yoyogi and returned to the Harajuku hostel, where I secured my luggage. Then I worked out hard. As I was moving and training my muscles, my mind was formulating ideas and strategies, storing some in my memory and throwing the rest out. I drank five tall bottles of water when I finished. It’s important to take in enough water during the night to keep your body working properly during the fast of the day. At 1:30 in the morning, I was showered and dressed, wearing my black nylon Nike suit and a black tee and my black uptowns, my gloves in my back pocket. I wanted my hands free, so I rocked a Black Jansport containing the few items I might need.

I stepped outside the Harajuku hostel expecting shit on the streets to be winding down, but the Harajuku party seemed at a boiling point, with all kinds of kids and kooks and characters milling around and mixing in with the young fashionable crews as well. Was it my imagination, or as I began walking, did a huge chunk of the crowd begin to move in the same direction as me? I was accompanied and followed by about a hundred and fifty youth and preceded by about eighty more, as we all walked and squeezed down the tight Harajuku alleyway to the train station. Feeling like an actor in

Thriller

, I played the corner as the freaks packed the compartment of what I discovered was the last train for the night.