Lost Worlds (27 page)

Luck was with me, though. My Cuna guide returned in a piragua with a man who looked far too old for paddling and poling. We said our farewells and I gave my guide the gift of a knife he’d admired when he watched me cut the fruit we’d been eating for the last few days.

Once we reached the Atrato the journey became relaxing. The old man was on his way to trade in Turbo (more odd bundles wrapped in banana fronds and tied with hemp) and we eased down the river through the northern swampy fringes, out into the vast delta, and across the shimmering Gulf of Urabá.

Turbo was as bad as I’d been warned. Its Wild West flavor had none of the charm of the old gold-mining towns of the United States. It was a seedy, forlorn place full of street gamblers and cheap-beer saloons and slouching

campesinos

who had come to this terminal point of the Pan American Highway in search of something they couldn’t seem to find and didn’t know what to do next. I celebrated the end of the journey by drinking my first cold beers in almost ten days, but they didn’t raise my spirits much. The place had an end-of-the-earth feel and I quickly set about making arrangements to travel by ship to Colón.

I couldn’t forget the invitation of the chief’s son in Paya—“You know you can stay if you wish.” Why the hell didn’t I stay in his tranquil village eating plantains and sketching the Cuna, at least for a while? Why all this constant movement? A glut of good-byes and not nearly enough “Thank you—I’ll stay.”

I’ll work it all out one day. Maybe….

I’m definitely not a sailor. Never have been, and by the look of present circumstances, never will be. I might not even be me much longer. Rarely have I felt so utterly vulnerable—helpless—at the questionable mercy of unfamiliar elements, dependent upon the skill and endurance of someone I hardly know. Oh—and facing the voids of self-doubt as my little backup security bungee ropes snap one by one, leaving me tumbling headlong into utter unpredictability—and terror. I don’t even know why I’m here….

An almighty crash!

What the hell was that?

The boat seemed to somersault in the heaving spray. We must have caught a side wave again. Much bigger than any of the others. Water poured over the rail like a miniature Niagara. I was hanging on with both hands, but I could feel my grip weakening.

Why doesn’t the thing bob back up like boats are supposed to? I’m looking into the waves now—I mean

into

them. They’re directly

below

me. They shouldn’t be there. If I lose my hold I’ll just tumble down into the maw of the maelstrom. And that’ll be it—one second—less than a second—and it’ll all be over and finished. No more heaving like a cork in a cataract, no more of this bone-jarring roller-coastering…. I’d be at peace. Drifting gently down, far beneath the churning waves. Drifting into silence. A lovely, benevolent, eternal silence….

It’s almost tempting. I’m sick of all this clutching and crashing and grabbing and churning. Is it wrong to ask for a little respite? I mean, how much more is this poor battered body of mine supposed to take? Dammit, it’s summertime down here. It’s not supposed to be like this. No one had warned me….

There are far easier ways of exploring the curled southern extremities of Chile. They’ve even built a new road through the Andes all the way down to the Patagonian and Tierra del Fuego peaks. A nice safe one-lane graded highway on the other side of the mountains, where skies are occasionally blue and winds only bend trees a little, not whole landscapes. There are even towns that boast 310 days of sunshine a year. The Chilean coast, on the other hand, is lucky to get 40! It would have been a beautiful quiescent journey—just me and the condors and the mountains and the vast Argentinean pampas to the east. I would have actually been able to see something. These impenetrable fogs and notorious “williwaw” winds and days of nothing but sodden grayness would have been as unlikely as glaciers in the Grand Canyon.

I could have slept on solid, unmoving earth or even in little roadside inns, eating the good stolid beef ’n’ beef breakfasts and dinners of this rolling cattle country. I could have had days of quiet meditation and relaxation—sketching a little, catching up on my travel notes, and polishing my soul. Generally mellowing out and bestowing a few modest indulgences upon my weary body and mind.

And lots more “could haves” too.

Only I didn’t.

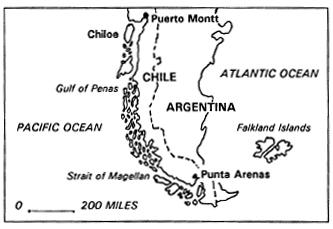

I didn’t do any of that. Instead, like a jolly gigolo, I allowed myself to be seduced by the idea of new experiences, new conquests, new adrenaline stimulants—the new aphrodisiac of a sea journey. On a boat. A small boat. Skimming across a purple ocean. Exploring the most magnificent (and undiscovered) fjord coast in the world. Forget the Norwegian fjords. The fjords of Chile are twice, three times the size. The whole Andean range rising up from jungle-clad bays and clefts to soaring snowbound peaks necklaced with glaciers that sparkle and wink under huge blue skies…. Oh—I’d done my homework. I knew that this part of Chile, only six hundred miles west from the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica, was a region notorious for its climatic idiosyncracies. Month after month of storms and gales from Cape Horn. All the way up the nine hundred miles to Puerto Montt. But I also knew—well, at least I’d been told by people who knew—that November was summertime here in these southern latitudes. A time of tranquility and restoration. A period ideal for easy exploration.

“Nobody’s written about this area,” I’d been told. “It’s one of the earth’s last real undiscovered regions,” I’d been assured. “You’ll be one of the first.”

I should have known better. The lure of “You’ll be one of the first” is always guaranteed to hook this particular fish. Brighter than an Apte Tarpan fly, as deadly as a Jock Scott or a Royal Wulff, the lure of those words always hides a barbed hook and I’ve had those barbs stuck deep in my psyche before as I’ve grappled in the soaring

tepuis

of the Gran Sabana of Venezuela, the treacherous terrains of Scotland’s Torridon, the fickle terrors of the Sahara. And all because of that damned phrase “You’ll be one of the first.”

You’d think I’d have learned to be a wise fish by now. Keeping to the deeper places. Ignoring the clever illusive flashes of bright lures….

Another crash!

Just as we were coming up to horizontal. And here we go again. Another Niagara. Another eye-to-eye meeting with that horrible green-gray morass of seething ocean directly below me.

I’m really fed up with this now. Honestly—I’m not kidding. I’ve had it. Sailing is for suicidal nuts. Men aren’t meant to sail. The snide, grinning dock hands at Puerto Montt had known it would be like this. All that nudging and nodding—they knew what it would be like. They may have even tried to warn me in their cocky supercilious way—but I wasn’t listening. I was off on another adventure. I only heard that damn phrase “You’ll be one of the first” and everything else was mere maunginess and mean-spirited pessimism…. I was deaf to defeatism. Hell—I may even have sniggered at them—laughing inside at the landbound. Poor unimaginative buggers—living their dull safe lives among the cranes and capstans and old warehouses. Never knowing the thrill of discovery. Never even catching a glimpse of the towering fjords.

I wish I was back with them now. They were the wise ones. I was the jackass. Just another arrogant ignoramus off to his doom among the unnamed islands and whirlpooling channels of this topographical tumult. This time I’d gone too far. There’d be no lucky hand of fate to lift me lovingly out of this seething mess….

It had all begun so calmly in Puerto Montt, where I’d come to satisfy a nagging curiosity about this strange remote region at the bottom end of the world that nobody seemed to know anything about.

As usual I’d made no prior arrangements, trusting to luck that there would be boats of some kind easing their way down the coast, through the narrow channels, across the notorious Gulf of Peñas and on down the Strait of Magellan to Punta Arenas.

I’d be following the historical wake of Ferdinand Magellan, who sliced through these seas for the first time in 1520 aboard his caravel

Trinidad

, or Sir Francis Drake, who, sailing his famous

Golden Hind

, discovered a safe if choppy route between cliffs and storms. Or even the poor Captain Sarmiento de Gamboa, who established some of the first communities in these southern extremities of Chile and later saw them desolated by isolation and starvation. Ah—what a journey. What a dream!

Of course I expected to hang around the docks and cafés of Puerto Montt for a few days looking for a lift. After the noise and swelter of Santiago, seven hundred miles to the north, this quiet Bavarian-flavored, end-of-the-line port town founded by German immigrants in the 1850s is a pleasant place for dallying. In this capital of Chile’s famous Lake Region I envisaged a couple of trips into the mountains playing tourist, but luck suddenly appeared abruptly on day two in the form of Peter Swales, an Australian sailor who, in his words, was attempting “a half-assed ’round the world thing with lots of holdovers!”

“Is Puerto Montt a holdover?” I asked him.

“Not from what I’ve seen. Don’t think there’s much point hanging about. Too quiet.”

“So where are you heading next?”

“South—down the coast. See the fjords. Have a look at the Magellan. They say that’s beaut sailing down there!”

Well—time to go for it, I thought.

“Do you need a deckhand? I gather it gets a bit rough.”

He looked at me and I looked at him. He was a wiry, short man of around forty with sun-frizzled hair, a deep tan, and unusually large brown eyes. He seemed honest and direct, like most Australians I’ve met on my travels.

“Who you pitchin’ for—yourself?”

“Sure. Who else?”

“Sailed before?”

“Not much.”

“Get seasick?”

“I expect so.”

“D’you know what a halyard is?”

“No idea.”

“Can you cook?”

“I’m a great cook.”

“Got some spare cash to share costs?”

“Not much.”

A brief pause, then a quick laugh from Peter and an extended hand, deep brown and laced with rope burns.

“Six in the morning we leave. You can sleep in the boat tonight if you want. I’m not going to get a girl in this place, anyway. ’Least, not for free.”

And that was that.

At six the following morning, as Peter had said, we left the harbor in his small boat,

Christine

, and began our nine-hundred-mile journey south through one of the wildest lost worlds in the Southern Hemisphere.

Just looking at a map of the world makes you curious about this ragtag coastline at the southern end of Chile. There are islands, hundreds of them, and deep gashes into the Andean spine (much deeper than those Norwegian fjord incisions). It’s been called “a topographical hysteria” and “the wettest place on the planet,” but on that first morning, as we drifted through light mists out of Puerto Montt, the thrill of new discoveries overwhelmed any sense of foreboding.

Unfortunately, the mists stayed with us most of that first day and well into the second, but at least the wind was “tame,” hardly twenty knots according to Peter but quite frisky enough for me.

We had planned to rest over in Castro, on the Isle of Chiloé (the last town of any size for hundreds of miles), but Peter had lost a key navigational map and didn’t fancy feeling his way through the shoals and islets in a fog.

“Listen, Peter,” I said, “let’s just give it a couple of hours. Maybe it’ll lift, and I’d really like to see Chiloé. After this, according to the map, we’re on our own. How about a few beers and a decent steak?”

Peter looked uncertain. There was something inside him—impatience, maybe—driving him on. I know those sensations well and find I have to fight them fiercely, otherwise my journeys would become nothing but mere mechanics of movement. I played an ace.

“I’m buying.”

That did it. He smiled and nodded.

“Ah—well, that makes all the difference. Now what I see is one of those gigantic Black Angus steaks falling off the edge of the plate, barbecued to a crisp on the outside, blood red in the middle, with a great pile of…”

So we waited and the fog lifted for us. Darwin cursed this place for its appalling weather, the Spanish explorers loathed it, but we’d been granted a period of grace and decided to make the most of it.

Three mottled brown pelicans, saggy-beaked and with enormous wingspans, kept us company as we sailed for shore watching the twin orange and lavender towers of Castro’s cathedral, the Apostal Santiago, rise up among lush green hills flecked with fields, orchards, farmhouses, and swirls of forest.

In such a fogbound, rain-scoured part of the world and on the edge of one of the most chaotic landscape and seascape combinations known to man, it was a delight to see the brightly colored little town edge closer. Startling canary yellows, vivid greens, turquoise blues, pinks, and mauves covered the tiny cottages, scale-clad like fish in wooden tiles, or

tejuelas

. They use the trunk of the local alerce tree to make these tiles and tradition has it that they bend outward every time it rains to keep the cottages dry and cozy.

The boats—even the people—were clad in the same array of brilliant colors. Chiloén women are notorious knitters—every spare minute they’re sitting on the doorsteps clicking away with their needles, catching up with the local gossip, and producing a boy’s sweater before dinner, when they vanish indoors to prepare their famous empanadas and strange dark stews (

cochajvja

), whose main ingredient seems to be black Chiloé seaweed, and the most traditional of their island dishes,

curante

, an odd blending of layered meats and seafood baked traditionally on heated rocks.

We tied up the boat near the harbor, close to a ragtag composition of

palafitos

, little cabins and houses built on high stilts to compensate for twenty-foot tides. At a dockside bar (bright pink shingles and violet-framed windows) a plump, apple-cheeked waitress was serving huge bowls of soup brimming with clams, mussels, scallops, and fish chunks, served with crisp seaweed cakes. Peter nudged me. “Stop gawking at that stuff. We’re in here for steaks. And you’re buying, right?”

“Right,” I said. He was a stickler for protocol.

We passed a small town market. All dressed in bulky sweaters, the women were prodding through piles of homespun scarves, mittens, and caps spread out on the ground. Others were selecting from fifteen different types of seaweed tied, compressed, bundled, or packaged in plastic bags, depending on the type, and all looking like some illicit haul of exotic jungle drugs.

One old man in a thick drooping leather hat and a woolen poncho sat on a stool presiding over his library of secondhand books and parchment-colored pamphlets. I picked one up with garish illustrations depicting the famous Chiloén legends of sea serpents, phantom galleons, boat-wrecking mermaids, forest trolls, a Dracula-like snake with a hen’s head that lives on human blood, and an enormous plumed horse said to be the favorite form of oceangoing transport for island witches.

On the last page was Chiloé’s most notorious spirit, El Trauco, an evil-eyed and bent-bodied goblin who turns modest maidens into passionate lust-crazed vamps and has been blamed for countless illicit unions and unexpected offspring among the island’s nubile nymphs. One gentleman with a large walrus mustache and wearing a felt Hamburg hat paused to peer over my shoulder at the page, winked, and muttered something that sounded rude in the local dialect. I felt as though I’d been discovered peeping into a pornography bookstore and hastily replaced the book.