Lost Worlds (26 page)

“And you are giving many things to me. This is my fourth plate of plantains! That’s why I’d like you to have this pen,” I said. “It belonged to my father and I’m sure he—”

“It is your father’s pen?”

“Yes.”

“Then I cannot accept. And you should not offer it.”

He was right. I was reluctant to part with it, but gift giving, I knew, was an important part of Cuna tradition and I had so little else to give.

“May I see your notebook?”

I handed him the damp dog-eared pad in which I recorded the journey and kept sketches of people and places I’d seen.

“You did these drawings?”

“Yes. They’re only rough.”

“They are very good.” He flicked through the pages and paused at a sketch I’d done of one of my Cuna guides.

“You draw people well,” he said.

“Thank you.”

“And I thank you for your offer of a gift. I cannot accept the pen of your father, but I would like you to do a drawing of me.” (Memories of Juan in the Venezuelan Andes!)

“I’d be delighted.”

“Good. In the morning we will meet and you can do the drawing. And tonight I would like you to sleep in one of our houses. Many of our village have gone with my father and their houses are empty. This man will show you where to go.”

A young boy was beckoned. The chief’s son said something quietly and I was led across the clearing to a small bamboo and thatch hut on the edge of the village. Except for two crudely carved stools, a pile of wooden bowls in the corner, and a bamboo mat, the place was empty. The supports consisted of thick lengths of bamboo tied together with hemp rope and topped with an elaborate roof of folded palm leaves secured by more rope. The boy vanished and returned a few minutes later with yet another banana-leaf plate of fried plantains and chunks of fresh avocado.

I spread my tent as a groundsheet over the mat, used a pile of my sweat-stained clothes as a pillow, and proceeded to eat yet one more evening snack. Outside was dark and the jungle chorus began on schedule. People moved about, their shadows flickering against the huts behind the cooking fires.

But once again, sleep came too quickly. Possibly in midbite of a particularly succulent slice of plantain, because I woke briefly at one point during the night and discovered my arm smeared in squashed banana pulp.

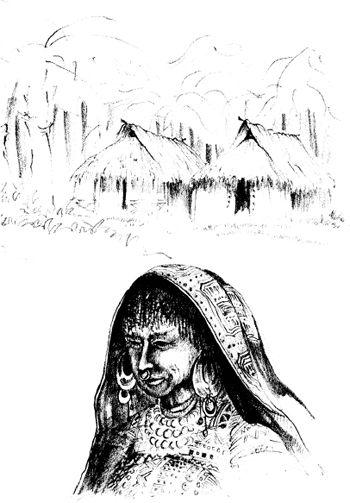

The next morning, after a breakfast of—you got it—fried plantain I sketched the chief’s son, who wore a feathered headdress and long necklaces of monkey teeth.

“To the Cuna, these teeth are very important,” he told me as I sat cross-legged outside his house. “Like the Christian peoples, we believe that after death we enter another life. There are many levels in this life and one thing that helps a man reach a high level is the number of his necklaces. These are the teeth of what you call the white-faced monkey. These monkeys are quite fierce and to kill such a creature is considered brave. So—the more monkeys you kill, the longer becomes your necklace of teeth, and the more honor you will have in the next life.”

He smiled as he talked, as if he didn’t quite believe in such ideas.

I was pleased with the sketch and handed it to him. He stared at it for a long time and then laughed.

“Yes. This is a fine gift, my friend. I will keep this in my house.”

Other Cuna clustered about, but he shooed them away and held the sketch to his chest.

“And I have something for you.”

He took off his headdress, reached around his neck, and lifted one of the necklaces over his head.

“Come here. Take off your hat.”

I removed the soggy, tattered canvas remnant of what started as quite a smart bush hat back in Panama City.

He placed the necklace gently around my neck. “Now you too will have good life in the next place!”

“But I didn’t kill these monkeys.”

“Ah—that doesn’t matter. I gave it to you, so it is the same thing.”

He winked as if to reinforce again the idea that he didn’t take all these beliefs too seriously.

“This is a wonderful gift. I shall keep this always,” I said.

“And I will keep this too,” he replied, holding the sketch like a precious piece of porcelain.

I spent the day wandering around the village, talking with the people and visiting their carefully nurtured gardens of bananas, mangoes, papayas, and avocados. With the exception of a few chickens and peccaries, the Cuna seemed to depend on a largely vegetarian diet. They looked fit and happy, proud of themselves and their reputation as of one of the most advanced of all Latin American native people.

I had hoped to watch one of their community meetings, a centuries-old practice of equitable democracy in which all tribal issues and disputes, including the selection of the chief, are resolved by discussion and consensus. But, with the present chief and many of his associates away on the San Blas Islands, the sturdy bamboo and thatch community house remained empty.

His son outlined some of the strict protocols of these community meetings. “They can be very complex,” he said. “The number of these meetings in a village tell you how important that village is. There are two main types—the chanting and singing meetings, where all the villagers come. The men who know the correct chants and songs are very important. Usually we vote them to chiefs. And then we have the special meetings for only the men when the conversation and discussion is very—what do you say?—like a church ritual—yes, like a ritual. We discuss something and when no one has any more to say, we reach a decision without voting.”

“By consensus, you mean?”

“Yes, that’s the thing—consensus. All together. About all kinds of things—about the things we grow, about government plans, about new schools. All kinds.”

“What happens if a meeting can’t reach consensus?”

“Well—if it happens very often, then the community will divide. A new village will be built and those who do not agree will live in the new place and have their own meetings.”

“So everything happens at a village level.”

“Very much, yes, but a few times every year we have congresses of all the villages. That is where my father is now. He has gone with some others to the islands where many of my people live, and they will discuss things that are important for everyone.”

“It all sounds very organized and very serious,” I said.

“Well, yes, I think it is. But we have many times of fun too. Many celebrations when people give gifts and have big hearts. If a son completes his education or marries or has a child—his family will have a big party and give away many things. We like to be generous. We do not like people who do not share what they have. That is not the Cuna way.”

“And the government allows you to live in this way—the way you choose?”

“Yes. They must. Since 1938 we have always had our own lands, the Comarca de San Blas, and since 1953 we have been allowed to run things—most things—by ourselves. That is why we can do things like protect our islands from hotels and other things, and keep our forests by working with people from other countries.”

“We talked a little last evening about the project you have for preserving the forest.”

“Well—for us it is very important. This is our home and no one really understands how valuable the forests are. There are lots of scientists all over the world trying to understand how the forests live. Maybe in the future we can have a balance between people and land, but first we must know how the forest lives and what is dangerous for it.”

“You sound as if you love this land very much.”

“How I cannot? It is my home and it is very beautiful—and very special for all of us.”

“Well—if you’re the next chief, the forest will be safe.”

“Aha! Maybe I would like to be chief one day. I have taken much time to learn the rituals and the chants—but, we are a democracy and even though I am the son of a chief, they may decide to have another person. That is the way it works with us.”

“I wish you the best of luck.”

“That is very nice for you to say to me. But whatever happens I am happy to be here. Being Cuna is very good!”

“I can see that!” I said, and our sudden laughter scared a couple of baby peccaries rooting in the scrub nearby and sent them scurrying across the dry earth in flurries of dust.

The following day I packed and was ready to leave when the chief’s son approached me again.

“I am sending a guide with you. There is no need to pay him. When you reach the Atrato River you must find someone in a piragua and he will take you maybe to Turbo.” He laughed. “Although I don’t know why you want to go to Turbo!”

“It’s the only way out once I cross the mountains into Colombia.”

“And you want to go out?”

“Not really. It’s so beautiful here.”

“You know you can stay if you wish.”

God—how many times have I been told this by people in quiet and peaceful places, all around the world. And I always feel the same way—torn between the flow of the journey itself and the temptation to stay and become a part of such places for a longer period of time.

I always remember something the notorious explorer-writer Richard Burton wrote: “If we stop moving and try to explain everything, we truly die; if we pause, if we take our gaze off the shimmering horizon for an instant, if we abandon the path in order to reflect or to plot our silly course, we go into exile.”

The impatient, impulsive Burton believed in movement for movement’s sake and some of his travel journals reflect a distinct lack of reflection. I know the temptations—the weighty momentum of the journey itself—but I also know the joys of staying awhile. And even if I don’t stay, in my heart I always promise to return after searching out the next lost world.

And, who knows, when all my wanderings are over, maybe I’ll return to this little village deep in the Panamanian rain forest.

It’s just that “maybe” that concerns me….

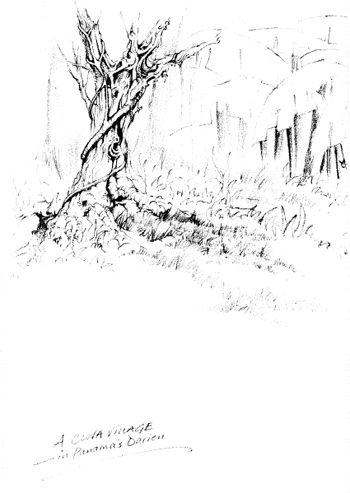

The next two days were hard going, climbing ever upward into the Darien ranges. At the highest point they reach over six thousand feet, but my guide insisted, in a Spanish dialect I could barely understand, that we were taking “the lower way.” Only it didn’t feel like that. The track, barely distinguishable among the riot of ferns, palms, and vines, wriggled like an inebriated snake up the endless muddy slopes. His panga was a useful instrument for clearing scrub in the thickest places, but we still had to somersault over enormous moss-covered trunks that had fallen across the track, and crawl in rotting slime up the steepest inclines.

Somewhere along the way we entered Colombia and paused in a small clearing at the top of the ranges to celebrate the views from our “peak in Darien.” Unfortunately, low clouds hid the view of the Pacific sixty miles or so to the west, but I could vaguely make out the Atlantic coast twenty miles to the east.

Between the coast and our aerie lay more jungle, which eventually merged into the vastness of Colombia’s enormous and little-explored swamplands. There was no sign of human habitation anywhere. The liquid landscape of this region would be an ideal candidate for “lost world” journeys—a mysterious green wilderness, through which silver-flecked streams wriggled into flat hazy infinities.

Maybe I’d do some exploring there after a little R and R in Turbo. (Another one of those damned maybes.)

The descent was almost as bad as the climb. Not quite so strenuous but leaving both of us like swamp creatures as we skidded and slid down through the tangle of vegetation, searching for a tributary of the Atrato that would carry me safely by piragua to the coast.

On the third day after leaving Paya we eventually found a stream, full and navigable following an overnight rainstorm that had battered my tent into a soggy, matted mess by morning.

My guide left me sitting on a pile of newly exposed roots by the water’s edge and went upstream to see if he could find someone willing to take me to Turbo.

Three hours passed which I had hoped to spend musing on my journey but was so plagued by mosquitoes and other biting

bichos

that I ended up wrapping myself in my wet tent and dozing in the sticky heat.