Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (52 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

When the Islamic Defenders Front demanded that the government deny Lady Gaga entry to Indonesia, Coordinating Minister for Legal, Political and Security Affairs Djoko Suyanto ignored them. People who didn’t like her could just stay away from the concert, he said.

Boom!

the FPI appeared in front of his office to protest. When a journalist called to ask for his comment, he replied by text message: ‘EGP’. EGP, from

emang gue pikirin

, is teenage slang that translates roughly as: ‘Like I give a shit’. I thought at the time that it was a pretty good reflection of most Indonesians’ attitude to extremism.

Most Indonesians seem to zone out groups like FPI because they feel life is too short to spend time worrying about a handful of zealots. A very few, however, are

forced

to worry, because those zealots are threatening their lives. Mosques belonging to minority sects are being torched by other Muslims, churches are being threatened and atheists jailed.

After my surreal visit to the sacred sex mountain of Gunung Kemukus, I trekked on eastwards as far as Lombok, the island to the east of Bali. Staunchly Muslim Lombok calls itself ‘The Land of a Thousand Mosques. It is home to a good few of gopping vulgarity: great purple pimples rising from the rice fields, flying saucers in lime green parked next to the market, roadsides positively spiky with newly erected minarets, some of them less than 500 metres from an existing mosque. Lombok is also one of an increasing number of places in Indonesia where members of the Ahmadiyah community have been evicted from their village. The Ahmadiyah are a tightly knit subset of Muslims who stick together, invest in education, work hard, and tend to succeed. They have been around since before independence – the composer of Indonesia’s national anthem was an Ahmadiyah – but the zealots have only recently turned on them.

Some talk of the Ahmadiyah as harmless crackpots, a bit like Scientologists. But a fair number of people I met, including a midwife in Lombok, a bus driver in Surabaya and a cop in the East Java island of Madura, grew apoplectic at the mere mention of the sect. All rushed to tell me that they were apostates, spreading false teachings. What false teachings? I asked, over and over. ‘They are just wrong. They are out to confuse the public. It’s dangerous,’ the midwife had said. No one could ever tell me how the Ahmadiyah’s beliefs differed from their own.

In fact, the sect is stained in the eyes of the back-to-Medina Sunni purists by the original sin of its founder. Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, a scholar in the British-India era, was a great self-promoter and declared himself a prophet. To Sunni purists, that’s sacrilege. There has been no prophet since Mohammad; anyone who believes otherwise cannot call themselves Muslim. Compounding their error, the Ahmadiyah are pacifist, they reject the notion of physical

jihad

in favour of a Holy War waged by the pen. But most of the people who take exception to them don’t even seem to know this.

Some years ago the villagers of Ketapang in western Lombok burned a community of around thirty Ahmadiyah families out of their homes; I decided to pay them a visit. I stopped at a school to ask directions to the village. ‘You won’t be welcome,’ warned the kindergarten head. And she was right. Ketapang grows like a tumour off a side road in rural Lombok, self-contained, hostile. I parked my bike at the roadside and walked in. A wall of stares. Silence.

I found a coffee stall arranged under a spreading mango tree. Three young lads wearing football strip – Juventus, Barça and one I didn’t recognize – were lying around playing with their cell phones. I ordered a coffee from the stall owner. She looked up from her grinding stone, then went back to smushing up chillies. I waited. She smushed. Someone else came in and asked for a Fanta; she served him straight away. Then she went back to smushing. I waited. After some minutes, one of the lads, with hair spiky enough to put your eye out, said something in the local Sasak language and she grunted and served me a coffee. I tried to start a conversation with the lads about football, but it was like pulling teeth. I moved on to the elections – various candidates for village head had strung their banners up between houses. Nothing doing.

All around the village it was the same. Everyone was monosyllabic, suspicious, guarded. One woman did answer my questions about the work she was doing: the whole village seems to subsist by making brooms out of bamboo poles and coconut fibre matting, an occupation that brings in 3,600 rupiah a day, about forty cents. But no one would talk about anything more general, like education, or corruption, or religion. And for some reason I just couldn’t bring myself simply to ask: ‘So, what happened to your Ahmadiyah neighbours?’

If the victors were this tight-lipped, I didn’t hold out much hope of getting a good chat going with the victims.

Lombok’s long-suffering Ahmadiyah community, it turned out, were the polar opposite of their former neighbours: effusively welcoming, though apologetic about their surroundings. They were living in a dilapidated government complex in Lombok’s main city, Mataram, about twenty-five kilometres from their village. The ‘Transito’ had been built in the 1970s as a stopover for transmigrants from Java or Bali as they headed further east. Now, plywood peeled in great sheets off the ceiling and buckets on the floor caught the rain that dribbled through the roof.

The whole community lives in a single large hall, divided up by thick brown curtains which don’t reach the ceiling. This makes two rows of ‘houses’, each about two metres by three metres. Ibu Nur, who had been especially welcoming, pulled back the curtain to show me her home as we passed. It looked like a cross between Ibu Nining’s tenement in Tanah Tinggi and the refugee camp that I had seen after the mudflows in Ternate: plastic storage boxes stacked up against the wall, school uniforms hung from a raffia clothes line, a sleeping mat rolled neatly back so that the kids could do their homework on the floor.

She and her family had lived here for almost seven years.

Nur invited me to come to evening prayers; everyone was heading out the back of the hall to a tiny prayer room which was squashed in next to the communal loos. Kids jostled to get up under the roof; latecomers overflowed into the courtyard and prayed in the rain. There was no loudspeaker, no sermonizing. A community elder, Pak Syahudin, led the prayers. Everyone else followed, and that was that. After prayers, as we sat in the gathering dusk watching the rain plop through the roof, I asked jokingly whether this counted as one of the mosques in this Land of 1,000 Mosques. ‘Hah! People here are so Holier Than Thou, but it’s what’s on the inside that counts,’ said Nur.

I asked why they thought the villagers of Ketapang had taken time out from making brooms to attack them. Nur and the other young women in the group put it down to ‘social jealousy’, a vague but ubiquitous term used in any situation where one community comes into conflict with some other group that is doing better economically. The Ahmadiyah had moved to the west Lombok village of Ketapang after being run out of the east of the island. They were better educated than the locals, they had better contacts and they worked harder. They got richer. It is the story of migrants all over Indonesia.

Pak Syahudin let them speak, then disagreed. For him, the spark was political. ‘Eight times we’ve been hounded out of whatever village we were in.

Eight times

. And every single time it is after the visit of some political bigwig or other.’ He mentioned a cabinet minister from the Islamic Moon and Star Party and a candidate for bupati from the PKS. Syahudin believed the attacks were deliberately provoked by people who thought there were votes to be gained by taking an uncompromising stance against a religious minority.

It’s quite likely that religious bigotry does produce votes in very local elections, where prejudices are more easily manipulated. But it doesn’t work at the national level. In the privacy of the poll booth, most Indonesians show no interest in being governed by people who want to mix politics and religion. In fact, support for Islamic parties, highest in the 1955 elections at around 44 per cent, has been on a steady slide since properly democratic elections resumed in 1999. In the 2009 elections, fewer than 30 per cent of voters opted for Islamic parties: the big three winners were all staunchly secular. And the opinion polls were predicting an even worse outcome for religious parties in 2014.

Despite this, the national government has recently done little to uphold the law and protect religious minorities. In 2011 over a thousand people attacked about twenty sect members in an Ahmadiyah mosque in West Java, killing three of them. Police arrested some of the mob. Then trucks of white-robed supporters with bullhorns started rocking up at the police station, threatening apostates and all those who support them. As a result, the police did not charge any of the attackers with murder. A dozen men were sentenced to a few months in jail for minor offences; the longest sentence went to one of the surviving Ahmadiyah members, for punching a man who came at him with a machete.

Sitting outside her miserable home in Lombok’s Transito, Nur put the government’s failure to protect minorities down to sheer cowardice. ‘They’re terrified of demonstrations. It’s as simple as that.’

Some thirteen years into Indonesia’s raucously democratic experiment, it was more or less a given that organizations such as the FPI would be on the streets in a flash if the government was seen to be defending heterodoxy. Jakarta might step in to protect religious minorities if it thought the electorate would take to the streets demanding religious pluralism, but that won’t happen. Most Indonesians support the idea of religious freedom in general, but members of the great orthodox Sunni majority are not going to storm the barricades and confront a handful of fanatics who have shown that they are willing to maim and kill, just to defend the rights of minorities that they think are crackpots. They just don’t care that much. Like the Coordinating Minister of Legal, Political and Security Affairs, most Indonesians don’t really give a shit what other people believe.

*

The verses are a call to proselytize, and to obey.

*

The talismanic word

merdeka

, meaning liberty but also national independence from Dutch rule, appeared in a Malay-Dutch word list compiled in 1603 with the meaning ‘Free Man’. It derives from Maharddhika, a Sanskrit word transposed by the Dutch as Mardijker and used to refer to freed slaves and their descendants.

*

’Tache once ordered my colleagues to pulp several thousand AIDS prevention posters because he didn’t like the photo of him we had used. ‘My moustache is crooked,’ he explained.

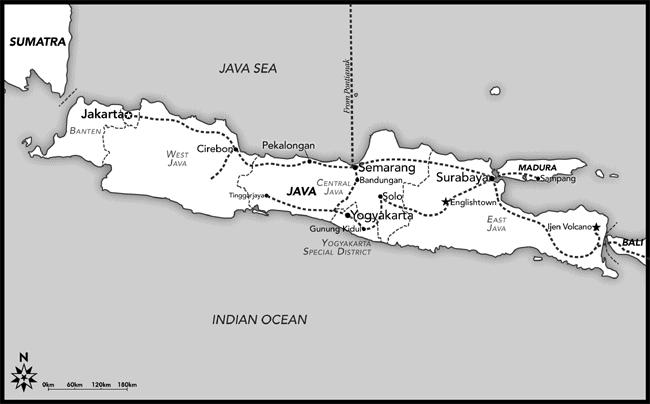

Map M: J

AVA

I had been on the roads and high seas of Indonesia for a year before I arrived in Java (that’s not counting occasional dashes through Jakarta, which is almost a nation apart). I had visited twenty provinces and all four of the biggest islands – Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Indonesian parts of New Guinea and, most recently, Borneo – as well as dozens of smaller islands, some too little even to appear on the map. By the time I had clambered off the boat from Pontianak, my thoughts about Java had been coloured over with the opinions that wash around all these other places. Java is a place of smooth, well-lit highways along which people in business suits drive sparkling SUVs to meetings where they will seal important business deals. In Java everyone gets a great education and has access to wonderful hospitals, although confusingly some of them are still rice farmers who work unreasonably hard to squeeze an incredible three crops a year out of their fertile soil.