Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (48 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

When I repeated this to a lawyer friend, she laughed. ‘It doesn’t depend on your class, just on your wallet. You know how it is here, justice goes to the highest bidder.’ In surveys of corruption, two-thirds of Indonesians rate the Attorney General’s office as ‘dirty’ or ‘filthy’. Only political parties and the national parliament are considered more corrupt. Recently, the relatively independent Commission for the Eradication of Corruption (KPK) has arrested several judges in the corruption courts for taking bribes to throw out charges against the accused. Judges find it easy to acquit defendants because prosecutors have taken bribes to prepare a case full of loopholes. And they are very bad at policing their own system. The KPK had to step in because a Judicial Commission set up to clean up the courts has been so hopeless. The most recent data show that in 2008, it received 1,556 reports of misconduct by judges. The commission investigated 212 cases and referred twenty-seven cases to the Supreme Court, which did not act on any of them.

The Dutch left a deeply flawed legal system, certainly. But Indonesians, whose independence-era leaders were often lawyers trained by the Dutch, have done little to change it. They more or less adopted the ‘native courts’ side of the colonial legal system wholesale, complete with poorly trained prosecutors, a criminal code written in a language that only a tiny handful could speak and designed by the colonial state to keep native subjects in their place, and a habit of being dictated to by a ruling class that stood above a court of law.

Nowadays, there are three times as many Indonesians as there were in the early 1950s, but only half as many court cases. The distrust of law enforcement starts long before anything gets to court, with the police. Over six in ten Indonesians think that the police are corrupt or very corrupt. So Indonesians often take the law into their own hands. People get beaten to death by angry crowds because they have been caught stealing a chicken, because they lost control of their car and knocked over a pedestrian, because a jealous neighbour has accused them of witchcraft. If one of these incidents happens to involve someone who thinks of themselves as ‘indigenous’ and someone who is thought of as an ‘immigrant’, a tiny incident that ought to be resolved at the police station or the magistrate’s court can turn into a minor civil war that costs hundreds of lives. With alarming frequency, mobs are turning on the police themselves. As I write this, in late March 2013, the newspapers tell of a sub-district police chief who was beaten to death as he led the arrest of a bookie who was running a gambling racket. Crowds closed in on the arresting cops after the bookie’s wife accused them of being buffalo thieves. This was one of thirteen incidents in which mobs attacked the police in the first three months of 2013 alone. As long as Indonesians believe the police and courts are rotten to the core – ‘Report the theft of a chicken and lose your buffalo,’ the Javanese saying goes – mob justice will continue to rule.

*

Joseph Conrad,

Almayer’s Folly

. New York: Macmillan and Co., 1895.

*

See Jamie S. Davidson,

From Rebellion to Riots: Collective Violence on Indonesian Borneo

. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

*

The classification system was incredibly complex, and shifted over time. Indonesian wives of Europeans and their children became European. Illegitimate children were European if the father acknowledged them. In addition, ‘natives’ could qualify as honorary Europeans at the whim of the Governor General; these people were called ‘Government Gazette Europeans’. Following pressure from a newly assertive Tokyo, all Japanese were accorded ‘European’ status in 1899.

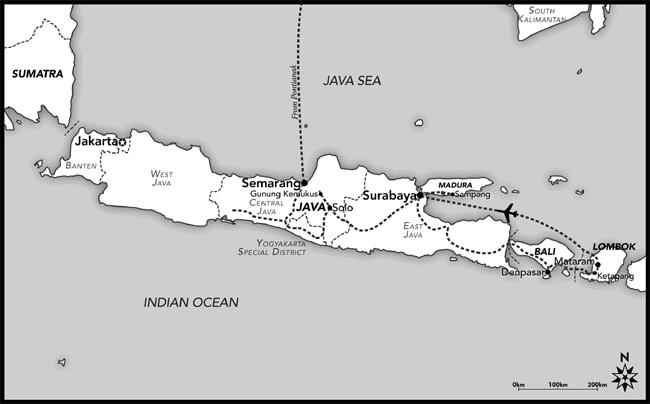

Map L: J

AVA

, B

ALI AND

L

OMBOK

Throughout my journey, I got my fix of world news by reading online newspapers in the internet cafes that are a relatively new addition to the townscapes of Indonesia. They sit below the ubiquitous cell-phone towers, close to the harbour or the bus station, perhaps shouldered in next to a nasi Padang restaurant. Generally, they are small shops furnished with cubicles that rise to waist height. About eighteen inches off the ground, often on an upturned crate, sit computer screens. Adolescents litter the floor behind the consoles. Girls are usually in gaggles in a cubicle, squeezing in front of the web-cam, then posting the pictures on Facebook. Boys are more often alone, doing on-screen battle with racing cars or dragons. Once or twice over the course of the year I saw people on Wikipedia, clearly doing their homework. But for most young Indonesians, the internet is pure entertainment. This is reflected in the language. To go online is

main internet

: to ‘play (on) the internet’. Usually, there’s a teenage boy with bad skin sitting up at a real desk playing computer games, acting as DJ for music that thuds from the wall-mounted speakers, and collecting money as people leave.

I attempted to zone out the music, the giggling and the

Zap! Pow!

sound-effects of the online gamers as I read the papers and tried to keep up with what was going on in the world. I was interested, too, in what foreign reporters were saying about Indonesia. ‘Indonesia’s Rising Religious Intolerance’, read a fairly typical headline in the

International Herald Tribune

. ‘Indonesia hit on rise in religious attacks’, said the

Financial Times

. ‘Rising religious violence “ignored” in Indonesia’, thundered the

Sydney Morning Herald

. The stories quoted the Setara Institute, which tracks religious freedom in Indonesia, and which documented 264 attacks on religious minorities in 2012. They told of the construction of churches blocked, of ‘deviant’ Muslims beaten and killed and their mosques burned to the ground, of atheists jailed. They harked not very far back to the bombs in a Bali nightclub that killed over 200 people in 2002, and the Marriott Hotel bombs in Jakarta in 2003 and 2009, in which nineteen others died. Islamist groups were proud to claim these attacks as their own work.

Many learned volumes have been written about the various flavours of Islam within Java and of other religions across the archipelago, many finely honed reports have dissected the relationship between Islam and politics in the Middle East, Indonesia and elsewhere in the world. The entrails of terrorist networks have been pulled out and chewed over, the bloodlines of extremism have been run through the sequencers. Some see an Arab invasion in progress, others a revival of indigenous forms of faith.

And yet in close to a year of travel, including in areas such as Aceh and South Sulawesi that have in the past fought for an Islamic state, I had heard people talking about religion only in the most mundane terms, as an immutable fact of life like food or sleep. Religious labels were occasionally stuck on to paroxysms of violence such as the war in Maluku, but after the fires had been put out, most people acknowledged that people had been fighting about money, jobs and political power, not faith.

People usually asked what religion I was, of course. To many foreigners the question seems intrusive, it treads on something that we think of as a private matter. But in Indonesia, religion is an inherent part of one’s identity. Since Suharto’s day, every citizen has had to state their religion on their ID card. ‘Belief in One God’ is the first precept of the state philosophy, Pancasila. One can’t be a Godless communist if one has a religion.

In Suharto’s day, Indonesians could pick from a menu of five religions: Islam, Hindu, Buddhist, Protestant or Catholic. Nowadays, they can also choose to be Confucian. There’s no room for the hundreds of locally specific beliefs like Mama Bobo’s Marapu religion in Sumba; those faiths have been redescribed as adat, and people who practise them have superimposed the ‘religion’ that fits best with their history and dietary traditions. No group that celebrates its true religion by feasting on pigs and cattle could be Muslim or Hindu, for example, so Mama Bobo’s ID card reads ‘KRISTEN’, which is shorthand for Protestant.

The one thing you absolutely can’t be as a good citizen is an atheist, which is what I am. I have every respect for other people’s faiths; I just don’t happen to have one myself. Sometimes, once I had become friends with someone that I had met casually on the road, I’d confess to some of the other lies I told in introductory chit-chat. Actually, there’s no long-suffering husband in Jakarta. In fact, I’m not on long leave from my job at the Ministry of Health. But I never, ever admitted to being Godless. To most Indonesians that would simply be incomprehensible, like saying I didn’t breathe.

And so I would profess the faith of my parents and say that I was Catholic. When I told people in heavily Muslim areas this, they would sometimes say ‘never mind’, as though not being Muslim was some kind of slightly embarrassing handicap. But they’d invite me home to stay anyway – it wasn’t a source of exclusion or discrimination.

Indonesians certainly live the rituals of their chosen religion more than most people do in Europe – many people routinely wear badges of their faith, a jilbab or peci cap on the head perhaps, a cross or a Buddha amulet around the neck. There is also an awful lot of collective praying at the mosque, the church, or the temple. I went to church more often on my Indonesian travels than I had in many years, and I also sat in quiet corners and listened respectfully to many sermons in mosques. It was simply expected, part of fitting in.

The most entertaining service I had been to on my travels was surely at The ROCK, a famous Mega-Church in Ambon, the capital of Maluku province. The Representatives Of Christ’s Kingdom can listen to their own radio station while waiting to hand their car over to the church’s valet parking service. I had visited not long after Christmas 2011, and found a cavernous, deliciously air-conditioned building festooned with flashing fairy lights, Immanuel banners and tinsel. A good half hour before the service – the second of four that day – the stalls and the balcony level were both heaving, and people were being directed to the overflow room to watch the service on a giant screen. We had a big screen of our own in the main hall, as well as several television monitors. All of them were counting down the minutes and seconds until the start of the day’s worship.

I spent some time admiring my fellow worshippers. The men were in suits or wearing batik or ikat shirts in ostentatious silks. The women tottered on six inches of royal-blue suede or diamanté platforms, here a cute sleeveless cocktail dress, there a gold flounce tight over the rump. But I had time, too, to look at the flyer I had been given as I came in. In Ohoiwait and the other towns in which I’d been to church we always got an Order of Service, with all the readings and prayers helpfully printed out. At The ROCK, the flyer said only:

Matthew 28: 18–20

*

Then, in English:

Bless the City

Change the World

Breakthrough

Building Family Values

Atmosphere

The other thing on the flyer was a bank account number for donations, though we were also all given envelopes, and there were see-through collection boxes at every exit of the hall, many of them already half filled.

The screen ticked from 09:59:59 to 10:00:00. Magically (since in twenty-five years I have never known anything start on time in Indonesia) the stage filled with choristers and the hall filled with praise. Mostly, people were belting out the words that popped up on the giant karaoke screen in front of us, but by the end of the first hymn some of my neighbours were already swaying, clapping and speaking in tongues, the tears streaming from ecstatic eyes.

After a few hymns, the choir melted away. It was replaced by a fresh-faced preacher with Boy Band hair wearing a puce silk tie. He was bringing Jeeeeezus to our lives.

Amin!

To our families.

Amin!

To our political leaders.

Amin! Amin!

To Indonesia.

Amin!

To our small, neglected and isolated islands.

Amin! Amin!

He started to up the tempo, then began to crack jokes about the state electricity company, PLN. ‘They say 2012 will be a year of darkness, and if you stick with PLN it certainly will be. Because only

Jeeeezus

shines his light every day of the year!’ Laughter, but also diligent note-taking. Though he kept the stand-up comedy going for over an hour, he managed to say only two things: 1) it is our duty to spread the name of Jesus, and 2) if we wait patiently Jesus will fulfil our demands.

At 11.55 on the dot, he wrapped up with a quiet ‘Amin’. There was one more rollicking hymn, and then, two hours to the second after the service started, it was all over and everyone tottered and flounced out to the hall.

I’m sure the whole format comes off some shelf in the American Bible Belt. And just like those faraway Mega Churches, the message was not of social engagement but of personal gratification. Nothing, but nothing was required of the congregation beyond the filling and depositing of envelopes. In the capital of the third poorest province in Indonesia there was not a whisper about equality in the eyes of God, not a mention that corruption was a sin against which we might unite, not the slightest suggestion that the Representatives of Christ’s Kingdom might help one another or anyone else. The tears, the speaking in tongues, this great outpouring of religious fervour was all about being entertained as we waited patiently for our next pair of royal-blue suede shoes.