Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (8 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

In May 1818 Trinity Church finally recommended an appropriation of three thousand dollars for a building that would serve as both schoolhouse and place of worship. Perhaps church leaders were motivated to act because of the threat of hundreds of blacks leaving the denomination. Or perhaps they saw a way out of their dilemma when George Lorillard offered the black parishioners “three lots of ground with a sixty year lease” on Collect Street, after which it was “to be held in fee simple, as a gift.”

14

So who was this George Lorillard whose business activities affected so many black New Yorkers in the early nineteenth century? He and his two brothers, Peter and Jacob, were members of what was then called Knickerbocker society. We owe this unwieldy name to Washington

Irving, the prolific fiction writer and essayist whose literary imagination was fueled by New York City and its environs. His fictional Diedrich Knickerbocker was the reputed author of a lengthy history of New York (1809), a satire of early Dutch settlers that mocked them for their foolish behavior caused by their addiction to strong drink and strong tobacco. The name came to apply to the actual descendants of these Dutch families; as their numbers shrank, the designation was extended to include English and also French Huguenot families like the Lorillards. A midcentury observer referred to the Knickerbockers as an “old aristocracy” and noted that “there is no strata of society so difficult to approach and apprehend.” Indeed, these families constituted a closed circle, marrying and socializing among themselves. They belonged to the same organizations. Many worshiped at Trinity Church, where they filled the ranks of the vestry.

15

The Knickerbockers were citizens of Gotham, another one of Irving’s inventions. Some two years earlier, Irving had published an essay introducing his readers to the city he named Gotham. The name first appeared in early English folklore, referring to a town in rural England named Goat’s Town. It was said that its inhabitants were wise men who deliberately acted like fools during the reign of King John (1199–1216). According to one account, they did so to avoid paying taxes; in another version, they hoped their crazy behavior would dissuade the king from a visit that would prove costly to them. From this came the observation that “more fools pass through Gotham than remain in it.” Like their medieval forerunners, Irving suggested, modern-day Gothamites might be fools in appearance only.

16

Some hundred years later, Gotham was reincarnated in a new form. In 1941, DC Comics adopted the term Gotham City for the home of Batman and his heroic exploits. It quickly came to be associated in the popular imagination with New York City. In contrast to Irving’s Gotham, Batman’s Gotham City is a dark and forbidding place. Its gigantic Gothic architecture dwarfs its human inhabitants. Its streets are grimy. It is vulnerable to epidemics and earthquakes, rife with crime and gang violence left unchecked by police corruption. Yet, despite this, it is a hub of commercial, financial, and cultural activity, containing a port and shipyards, banks, museums, and a variety of industries.

This Gotham, just like Irving’s, is pure fantasy, yet it describes with uncanny accuracy the city that men like the Lorillards were building. Manhattan was fast becoming a thriving commercial center, controlled by a powerful elite whose entrepreneurial zeal enabled them to make great fortunes.

The Lorillard brothers, George, Peter, and Jacob, were the sons of Pierre Lorillard, a French Huguenot who settled in New York in the mid-eighteenth century and quickly made a name and fortune for himself as an importer, manufacturer, and seller of tobacco and related products. A fervent patriot, Pierre was executed by Hessian soldiers during the revolutionary war. His wife carried on the business until their first two sons, George and Peter, were old enough to take over its management, which they did with considerable success. The third son, Jacob, entered the leather tanning industry. The family quickly became part of New York’s ruling Knickerbocker class.

17

In contrast to Irving’s depictions, these real-life Knickerbockers went to great pains to portray themselves as an aristocracy noted for its dignity, sobriety, work ethic, church attendance, and philanthropy. Beneath this facade, however, lay a ferocious determination to turn New York into the hub of the nation’s commercial, industrial, and financial activities and make a lot of money in the process. They did so in a variety of ways. Some owned large plantations along the Hudson River, others congregated in the city where they engaged in manufacture; many, like Boston Crummell’s former master Peter Schermerhorn, were slaveholders. But it was shipping, in all its forms, that dominated. Abiel Low, father of the future Brooklyn and New York mayor Seth Low, increased his wealth by opening up markets in China and founding the prestigious firm of A. A. Low and Brothers. Industries related to shipping grew at a fast pace; Schermerhorn was a ship’s chandler, supplying vessels with marine equipment and provisions. Auction houses sold imported goods. Private banks extended credit to merchants, while insurance companies gave them the confidence to trade.

To an astonishing extent, New York’s merchants benefited from slavery, mostly by trading in goods produced by slave labor. In these earlier decades, the major imports were sugar, molasses, rum, coffee, and cocoa brought in from the West Indies, which in turn gave rise to a host

of industries—distilleries, sugar refineries, and so on—run by men with solid Knickerbocker credentials. In the 1720s, for example, one Nicholas Bayard built the city’s most successful sugar manufactory. At century’s end, his son sold it to a merchant who converted it into a tobacco and snuff factory.

18

Also a slave crop, tobacco was another important commodity. Some of America’s most prominent men were involved in its trade. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were tobacco farmers, and a majority of the signers of the Declaration of Independence had tobacco interests. It was, in fact, the British taxation of tobacco that the founding fathers objected to most strenuously. Pierre Lorillard and his friends imported their tobacco from Virginia, South Carolina, Kentucky, and other southern states and then resold it at auction. Lorillard eventually gave up trade to go into snuff manufacture, and set up a shop on the High Road to Boston. It was this business that his sons, Peter and George, took over after their father’s death. They moved the store to Chatham Street and added cigars to their list of products for sale; Peter even patented a machine for cutting tobacco.

19

As successful as his two brothers, Jacob Lorillard went into the leather tanning business, which was concentrated in an area of Lower Manhattan known throughout the nineteenth century as the Swamp; originally called Greppel Bosch (meaning a “swamp or marsh covered with wood”), the area lay slightly southeast of Collect Street. Later on, members of my family moved into that neighborhood. In the late 1840s Albro Lyons operated a boardinghouse for black sailors on Pearl Street, and he eventually consolidated the boardinghouse and his family’s home in a residence on Vandewater Street. By the 1850s, Philip White lived down the block from him and established his drugstore at the corner of Frankfort and Gold Streets. Although he did not invent a machine as had his brother Peter, Jacob understood the importance of technology. Ahead of his competitors, he was the first to introduce into the Swamp a new rolling machine that improved the drying of hides.

20

Knickerbocker families soon realized that they could increase their wealth not only through trade and manufacturing, but also through monopolization of landownership, control of the real estate market, and speculation on the city’s increasingly valuable property. At the

end of the eighteenth century, Manhattan was undergoing a period of unprecedented growth. Its population doubled from 31,131 in 1790 to 60,529 in 1800. Economic activity boomed. The city rapidly expanded north. Most of Lower Manhattan from Broadway to the East River was owned by Trinity Church and six Knickerbocker families, Bayards, Stuyvesants, and others whose farms ranged between one hundred and three hundred acres. They had built their original homes, manufactures, and stores on this land, but they now began laying out and paving new streets, on which they constructed new and grander residences. They also divided their land into lots to sell, lease, or build rental properties—all at great profit. So began Manhattan’s first real estate bubble, which lasted until the Panic of 1837.

21

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, all three of Pierre Lorillard’s sons were active participants in this real estate frenzy. They acquired property in the areas where their manufactures were located, Jacob in the Swamp on Ferry and Gold Streets, Peter and George on Chatham Street near their tobacco manufacture. But they also bought land on just about every street in Lower Manhattan, including Collect Street.

George Lorillard had sold or leased land on Collect Street to black New Yorkers. But he and his brothers had also taken from them. When black parishioners petitioned Trinity Church in April 1795 for help in buying a “burial place to bury black persons of every denomination and description whatever in this city whether bond or free,” it was because the Negroes Burial Ground was being sold from under them. As speculators in real estate, George Lorillard and his brother, Peter, were indirect participants in this destruction, buying a portion of the land that had once been part of it.

A court case,

Smith, ex dem. Teller, v. G. & P. Lorillard

, tells the following story. In January 1795, a group of men of solid Knickerbocker stock—Henry, John, and Samuel Kip, Abraham and Isaac Van Vleeck, Daniel Denniston, and the estate of the deceased Samuel Bayard (from

the prominent sugar and tobacco family) obtained a deed of partition from the city of New York granting them permission to divide the Negroes Burial Ground into several lots. On today’s map, the property extended from Broadway to Centre Street, and from Chamber Street north to Duane Street. Originally, the land had been part of the city’s Commons, but in the mid-seventeenth century the government gave it to one Sara Roeleff for services rendered in negotiations with Native Americans upstate. At her death in 1693, Roeleff bequeathed the property to her several children; disputes among her heirs, executors of her will, and later descendants left the property largely unused. Most New Yorkers simply continued to think of it as part of the Commons, that is, as public land. But for New York’s black population, this was the place allotted to them to bury their dead. In the 1790s, the Roeleff heirs recognized the enhanced value of the ground, took control of it, and agreed to its partition. One year later, Peter and George Lorillard bought a piece of this land from Bayard’s estate for 560 pounds (although they were later obliged to return it to a Bayard heir in 1811).

22

As an early black institution, the Negroes Burial Ground antedated the founding of St. Philip’s by a century. For New York’s eighteenth-century black population, it was a hallowed place where they gathered to bury their dead and honor their memory. It was in use as far back as 1712, or perhaps even as early as 1697, when Trinity Church decided that blacks, whether free or enslaved, could no longer be buried in its cemetery. For much of the eighteenth century, the burial ground barely lay within the city limits. It was located between the palisade, which protected the city from attacks by French and Indians, and the Collect (Kalkhook) or Fresh Water Pond. Covering some seventy acres, Collect Pond was fringed by marshland created by its many outlets, and surrounded by wooded hills. A later account of the burial ground published in

Valentine’s Manual

in 1847 described its location as a “desolate, unappropriated spot, descending with a gentle declivity toward a ravine which led to the Kalkhook pond. … Though within convenient distance from the city, the locality was unattractive and desolate, so that by permission the slave population were allowed to inter their dead there.”

23

Destroyed and built over, the burial ground was rediscovered in 1991; a mere fraction of the skeletal remains buried there have been retrieved. To date, there is a dearth of information concerning it. Black families who used the Negroes Burial Ground throughout the eighteenth century have left us no written documents. Whites have provided a few accounts, although none are contemporaneous. The cemetery’s archive resides in the bones themselves and the occasional artifacts found with them. They need to be unearthed, read, and interpreted.

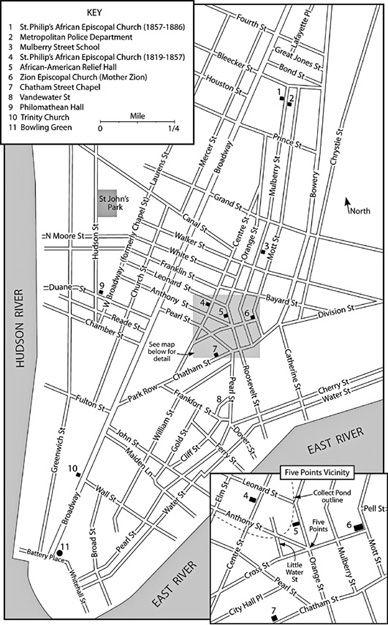

Lower Manhattan, 1836–1850 (Courtesy John Norton)

Here’s some of what we do know. The

Valentine’s Manual

account briefly notes that many early black inhabitants “were native Africans, imported hither in slave ships, and retaining their native superstitions and burial customs, among which was that of burying by night, with various mummeries and outcries.” Official documents of the time record that the city prohibited night burials and limited the number of mourners to twelve out of fear of insurrection. Anthropologists currently studying the site have produced additional information. During excavation, they discovered more than two hundred cowrie shells, thought to symbolize the sea and thus the return of the dead across the Atlantic to Africa or the afterlife. Other evidence suggests that the deceased were wrapped in shrouds held together by straight brass pins and buried in plain wood coffins. On the lid of one of the coffins ninety-two nails were found hammered in a heart-shaped design, perhaps a Sankofa symbol representing a turning of the “head toward the past in order to build the future.” Finally, all the bodies were placed with their heads toward the east, suggesting that when the dead awoke, they would face the rising sun and their African motherland. What the bones and artifacts do not, cannot, yield, however, is any information about the “mummeries and outcries” that accompanied the nighttime burials.

24