Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (3 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

But the lifespan of rituals may be tenuous. If not carefully maintained, rituals fade into oblivion. In the face of such dangers, societies often turn to more material forms of remembering, hoping that these will leave a more permanent physical mark. They record events in writing. They create objects—monuments, statues, tombstones, plaques—and preserve places as embodiments of memories. Old, disused buildings may become living testaments to the past.

Throughout the nineteenth century, black New Yorkers worked hard both to preserve memories of a past history of oppression and resistance

and

to create new memories of current events they wanted future generations to hold on to. Early in the century, they held celebrations every January 1 to mark the end of the United States slave trade in 1808, and every August 1 to remember West Indian emancipation in 1834. Along with the rest of the nation, northern blacks commemorated Independence Day, but many chose to celebrate July 5th rather than the 4th to remind themselves and the nation of their continued exclusion from full political and civil equality. As devout Christians, black Americans repeatedly turned to the Bible to cast their history of oppression and yearning for deliverance through Old and New Testament stories. They interpreted their history of New World suffering through the lens of the passion of Christ; they gave the title of Moses to leaders like Harriet Tubman who willingly risked their lives to free the enslaved.

At the same time, societies forget. Sometimes they simply choose to abandon memories of events that retrospectively strike them as insignificant or unworthy of commemoration. Or they may have the will, but not the resources, to remember. Communities can hardly hope to enshrine past memories when funds are not available to erect a monument, when literacy is not assured, or when writing is an expensive luxury

rather than a common daily practice. Even if created, without the means to preserve them written texts will eventually crumble at the touch, monuments and buildings fall into disrepair or vanish entirely.

Despite their best efforts, nineteenth-century black New Yorkers were often unable to create long-lasting memories to pass on to future generations, a sober reminder that memorializing can never be taken for granted. Financial woes forced early newspapers like

Freedom’s Journal

or the

Colored American

to stop publication after only a couple of years. At century’s end, black leaders failed in their plans to create a memorial in honor of Peter Guignon’s former schoolmate Henry Highland Garnet, a Presbyterian minister and radical reformer who had called for slave insurrection as early as 1843, actively recruited black soldiers during the Civil War, and later served as a United States minister to Liberia, where he died in 1882. Over time, many issues of later newspapers like the

New York Freeman

have simply disappeared as have entire years of its successor, the

New York Age.

All too often, underfunded communities lose ownership of their memorials—whether written texts or physical monuments—or the authority to preserve them. City officials may heedlessly, or perhaps deliberately, destroy such memorials in order to make way for the new or to erase reminders of a history deemed worthless or best forgotten. Consider the fate of the Negroes Burial Ground. Part of the City Commons, at the beginning of the eighteenth century it was the only cemetery in which black New Yorkers could bury and honor their dead. By century’s end they were helpless in preventing New York’s wealthy landowners from repossessing the land and carving it into lots as part of the real estate frenzy that had overtaken Lower Manhattan. All memory of this African American sacred place was lost until 1991 when the General Services Administration (GSA) announced plans to build a vast federal office complex on the site. In excavating the area, archaeologists found many human remains. Black communities in New York and throughout the nation galvanized to prevent the GSA from proceeding with construction. They held public meetings and organized commemorative ceremonies at the site in honor of their dead ancestors. After a two-year struggle the activists prevailed. In 1993, the federal government

designated the burial ground a National Historic Landmark, and in 2006 a National Monument, the African Burial Ground Memorial Site. Since 2005, the Schomburg Center in conjunction with different federal agencies has celebrated the preservation of the burial ground in annual “reinternment ceremonies.”

4

In 2010, a museum opened on the site.

Forgetting may also have deeper roots. If a group’s history has been one of violence and oppression, of physical and psychological wounding, later memories may result in cultural trauma. As with Morrison’s Sethe, remembering the past simply becomes too painful, creating a festering wound that will not heal, a shame that burns and scars the soul. Such were the reactions of many black New Yorkers after the Civil War. Alexander Crummell, for example, worried out loud about how black Americans should handle their prewar history, insisting that the constant recollection of the slave past was a pernicious habit, a morbid obsession, a form of mental enslavement. “For 200 years,” Crummell declared in 1885, “the misfortune of the black race has been the confinement of its mind in the pent-up prison of human bondage. The morbid, absorbing and abiding recollection of that condition—what is it but the continuance of that same condition, in memory and dark imagination?”

5

Browse through the shelves of books about nineteenth-century New York history at your local library and here’s what you’re likely to find: at one extreme, rags-to-riches stories about how men like John Jacob Astor came to New York from Germany with nothing in his pockets, built a fabulous fortune, and helped turn the city into a great metropolis; biographies of famous mayors like the upstanding Philip Hone or the corrupt Boss Tweed; and accounts of the growth of Wall Street, the creation of Central Park, or the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. At the other extreme are tales of poverty-stricken Europeans fleeing to New York in search a better life, such as Irish peasants escaping the potato famine of the 1840s; descriptions of the deplorable conditions of

the slums in which they huddled together; and tales of the criminal activities of neighborhood gangs. Bringing the two extremes together are meditations on the disparities of wealth and poverty that resulted in a highly combustible mix and frequently erupted in violence.

Yet a sense of incredible optimism often seems to pervade these histories. The Statue of Liberty and Emma Lazarus’s poem engraved on its base best sum up this can-do spirit. “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore,” Lady Liberty cries out in welcome: “I lift my lamp beside the golden door.” With few exceptions and until fairly recently, however, historians have tended to turn a blind eye to the degree to which the “yearning to breathe free” of black New Yorkers has so often been thwarted, if not actively resisted. Historians were once reluctant to acknowledge that slavery existed in the state until 1827, that the city’s commercial ties to the slave South and the Caribbean persisted until the Civil War, and that its wealth was founded in large part on slave labor. They also refused to recognize the highly qualified nature of black freedom after emancipation and the many acts of violence perpetrated with stunning regularity against black New Yorkers. Such admissions would have blatantly contradicted the ethos of liberal individualism that, we’ve been told, laid the foundation of New York’s emergence as a world metropolis.

It’s only in the past couple of decades that New York historians have undertaken serious study of the city’s early black population. They have focused on New York’s dependence on slave labor and the systemic discrimination that maintained blacks in an underclass status. At the same time, they have emphasized the presence of an early black elite that counters racist notions of black Americans’ inferiority and incapacity to be civilized.

6

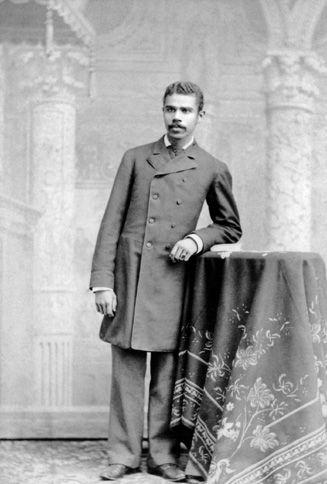

Yet to this day few nineteenth-century black New Yorkers figure in history books: Alexander Crummell; James McCune Smith, Philip White’s mentor, a highly respected doctor, writer, social activist, and ally of Frederick Douglass; radical reformer Henry Highland Garnet. Others receive a bare mention: Charles Reason, professor of belles lettres; his brother Patrick Reason, an early African American artist and engraver; George Downing, abolitionist and close friend of

Charles Sumner. As minor actors on the stage of history, men like Peter Guignon and Philip White are altogether absent.

Despite his admonition not to give in to morbid recollection, Crummell knew that it was impossible fully to suppress memories of the past. So he urged his contemporaries—Peter Guignon and Philip White among them—to avail themselves of “hope and imagination” in order to transform their memories into a “stimulant to high endeavor” and memorialize their history as one of dignified struggle for future generations to build on.

7

So what happened to my family’s memories? Did my great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather disregard Crummell’s advice? Or had they tried to pass memories down to future generations, but failed? If so, why?

In the absence of any concrete information, I’ve tried imaginatively to reconstruct why and how this process of forgetting happened. Philip White’s middle daughter, Cornelia, was my grandmother; she married Jerome Bowers Peterson shortly after her father’s death. Both had come of age in the waning years of the nineteenth century, shared the same ethical values and moral sensibility as the older generation, cherished the same collective memories, and attended many commemorative celebrations with their elders. I believe it was the next generation, that of my father Jerome Sidney Peterson and my aunt Dorothy Randolph Peterson, who turned their backs on the nineteenth century’s collective memories. Neither ever volunteered much information about our family, and I never bothered to ask. I have no idea whether they would have answered my questions, but in any event my aunt died in 1978 and my father in 1987 after a twelve-year illness that severely impaired his memory.

Maybe an unbridgeable generation gap had opened between my grandparents’ and my father’s generations. My father and aunt reached adulthood in the 1920s. I’m guessing that as the Harlem Renaissance

got under way, accounts of nineteenth-century black New Yorkers held little meaning for them. They had had no direct experience of this earlier history and could not fit it into their new twentieth-century context. Listening to stories about their forebears, they might well have dismissed them as hopelessly old-fashioned. They did not believe that their future lay in preserving the tight-knit community, time-honored traditions, and deeply felt values of respectability that had guided earlier generations.

More troubling, it’s also possible that since they had

not

participated in the struggles of the nineteenth century, this younger generation felt their traumatizing effects to a much greater extent. They might well have felt the degradation that accompanies humiliation and violence, but none of the pride and empowerment that come from determined resistance. They might have felt only shame about family members or acquaintances who had been slaves, domestic servants, or victims of racial violence. Such feelings might have convinced them that this was not a story to pass on.

Psychologists also remind us that memory crises are often brought on by personal family traumas. I thought back to a story in our family’s more recent history that my father and aunt

had

mentioned, though briefly and reluctantly. They had a much beloved older brother, Philip, named after his grandfather. He drowned at sea one summer day, eerily at almost exactly the same age as Peter Guignon Jr. half a century earlier. I turned to my oldest sister for details. The three children had gone to the beach unaccompanied. A strong undertow caught them by surprise. My aunt attended to her baby brother, assuming that Philip would be strong enough to swim to shore on his own. When she turned around, he was gone. His body was never recovered. Grievances festered under the surface, never to be brought up, aired, and much less resolved. According to my sister, either my aunt blamed her mother for not being present, or Cornelia blamed her daughter for not saving Philip. Or maybe it was both.

Either way, my aunt rebelled and engaged in behavior that her family considered highly unrespectable. She moved out of Brooklyn and up to Harlem on her own where she became a schoolteacher. She hung

out with the newcomers of the Harlem Renaissance. She became an actress. Exerting a powerful influence over her baby brother, she took my father with her. For better or for worse, they loosened their ties with the past to become New Negroes in Harlem, Greenwich Village, and abroad in Paris and other places. They imagined themselves as modern cosmopolitans, as citizens of the world, eager to encounter and experience other cultures. As an adult, my father worked in the field of international public health and our family spent years abroad in Beirut, Lebanon, and Geneva, Switzerland. He never said much about his own experiences growing up.