All Hell Let Loose (97 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

For the Allies, powerful relief was at hand as reinforcements were fed into the line, while the German predicament worsened by the hour as American artillery delivered pulverising bombardments. ‘My sergeant and I jumped into a ditch,’ wrote SS senior NCO Karl Leitner about his own experience on 21 December. ‘After approximately ten minutes a shell hit to the right of us, probably in a tree. My sergeant must have been badly wounded in the lung – he just gasped, and after a short time died. I had taken a piece of shrapnel in my right hip. Then a shell exploded in a tree behind. A piece of shrapnel hit me in my left ankle, other fragments slashed my right foot and ankle. I pushed myself half under my dead comrade … Fragments from another shell hit me in the left upper arm.’ It was several hours before Leitner was rescued and taken to a dressing station, during which the American barrage never let up.

Montgomery was given command of the northern sector of the front, and deployed formidable forces ready to meet the Germans if they reached the British armoured line, as most did not. On 22 December the weather cleared sufficiently to allow the Allied air forces to fly, with devastating consequences for the panzers. The German armoured spearheads advanced sixty miles at their furthest point, Foye-Nôtre-Dame, but by 3 January Hodges’ and Patton’s armies were counter-attacking north and south, while Model’s tanks had exhausted their fuel and momentum. On the 16th the two American pincers overcame deep snow as well as the enemy to meet at Houffalize. The Germans had suffered 100,000 casualties out of half a million men committed, and lost almost all their tanks and aircraft. Wehrmacht infantry captain Rolf-Helmut Schröder said of his own part in the Battle of the Bulge, ‘We finished the battle where we had started it; then I knew – that’s it.’ In January 1945 Schröder acknowledged the inevitability of Germany losing the war, as he had declined to do a month earlier.

The Allies lacked sufficient nerve to attempt to cut off the German retreat; Model’s forces were able to withdraw in good order, with American forces following rather than crowding them. Eisenhower was content merely to restore his front, after suffering the most traumatic shock of the north-west Europe campaign. The Ardennes battle left a legacy of caution among some commanders which persisted until the end of the war. ‘Americans are not brought up on disaster as are the British, to whom this was merely one more incident on the inevitably rough road towards final victory,’ in the sardonic words of Sir Frederick Morgan.

‘The record of accomplishment is essentially bland and plodding,’ wrote that magisterial American historian Martin Blumenson. ‘The commanders were generally workmanlike rather than bold, prudent rather than daring, George S. Patton being of course a notable exception.’ Yet if Patton’s reputation for energy was enhanced by his part in restoring the Ardennes front, his instinct for indiscretion remained undiminished. Visiting a field hospital, he almost committed another blunder to rival his assaults on combat-fatigue cases in Sicily. Asking one man how he had been injured, he exploded when the soldier answered, ‘I shot myself in the foot.’ Then the victim, whose ankle was shattered, added, ‘General, I’ve been in Africa, Sicily, France and now Germany. If I was going to do this to get out of the service, I’d have done it a long time ago.’ Patton said, ‘Son, I’m sorry, I made a mistake.’

The worst victims of the Ardennes offensive were the German people. Most now cherished ambitions only to see the Western Allies, rather than the Russians, occupy their cities and villages. After the shocks of December 1944, however, strategic prudence became the theme of Eisenhower’s operations. His armies’ subsequent advance into Germany was sluggish, influenced by a morbid anxiety to avoid exposing flanks to counter-attack. The Russians in the east, meanwhile, became important beneficiaries of Hitler’s losses: when they launched their own great offensive on 12 January 1945, many of the German tanks which might have checked their advance lay wrecked on the Western Front. The Ardennes battle, by dissipating Hitler’s armoured reserves, hastened Germany’s end, and not in a fashion to its people’s advantage. It ensured that the Red Army, rather than the Americans and British, led the way to Hitler’s capital. Only on 28 January did Eisenhower’s forces reoccupy the line they had held before Hitler launched

Autumn Mist

.

While the struggle in the Ardennes dominated headlines across much of the world, in Italy the Anglo-Americans continued their thankless, yard-by-yard struggle up the peninsula. Many Allied soldiers became increasingly embittered by the belief that they were suffering shocking privations for scant purpose or recognition. In some units, discipline became precarious. A platoon in Lt. Alex Bowlby’s infantry battalion formed up to deliver a collective protest when they heard that a despised officer had been recommended for a Military Cross. The recommendation was cancelled, but Bowlby sensed that his men were not far from mutiny, reluctant to participate in patrols or attacks. It has been remarked that Bowlby’s unit was untypically weak, that some regiments sustained higher morale and greater determination, which is undoubtedly true. But it was sometimes hard to persuade soldiers to risk and indeed sacrifice their lives when they knew that the outcome of the war was being determined elsewhere.

The last phase of the Italian campaign, in the spring of 1945, was by far its best-conducted, because the Allies belatedly appointed good generals. Lucian Truscott succeeded Clark at US Fifth Army in December 1944, and Richard McCreery took over the British Eighth Army from Oliver Leese. Both men displayed an imagination their predecessors conspicuously lacked, especially in avoiding frontal attacks. The push across the Po valley, admittedly against much-depleted German forces, was a fine military achievement, albeit too late to have much influence on the war’s endgame.

But there were some men fighting in Italy who had special reasons for questioning the campaign’s value. The Yalta conference in early February made it plain that, following victory, a communist government would rule Poland, and that the east of the country would become Russian soil. On 13 February the Polish corps commander in Italy, Gen. Władysław Anders, sent a letter to his British commander-in-chief, reflecting on the sacrifices that his men had made since 1942: ‘We left along our path, which we regarded as our battle route to Poland, thousands of graves of our comrades in arms. The soldiers of II Polish Corps, therefore, feel this latest decision of the Three-Power Conference to be the gravest injustice … This soldier now asks me what is the object of his struggle? Today I am unable to answer this question.’ Anders seriously considered withdrawing his corps from the Allied line, until dissuaded by McCreery. The Poles clung to vestigial hopes that their fighting contribution to the Allied cause might yet make possible some modification of the Yalta terms in their favour. But the reality, of course, was that each of the conquering nations would arbitrate the future of the countries it occupied in the fashion that it deemed appropriate. Stalin’s soldiers were already in Poland, for which Britain and France had gone to war, while the Western armies were far away.

1

BUDAPEST: IN THE EYE OF THE STORM

At the end of October 1944, Heinrich Himmler delivered an apocalyptic speech in East Prussia, setting the stage for the final defence of the Reich: ‘Our enemies must know that every kilometre they seek to advance into our country will cost them rivers of blood. They will step onto a field of human mines consisting of fanatical uncompromising fighters; every block of city flats, village, farmstead, forest will be defended by men, boys and old men and, if need be, by women and girls.’ On the Eastern Front during the months that followed, his vision was largely fulfilled: 1.2 million German troops and around a quarter of a million civilians died during the futile struggle to check the Russian onslaught. So too did many people whose governments had rashly allied themselves with the Third Reich in its years of European dominance, or who had volunteered to serve the Nazi cause. One-third of all German losses in the east took place in the last months of the war, when their sacrifice could serve no purpose save that of fulfilling the Nazi leadership’s commitment to self-immolation.

Among those who found themselves in the path of the Soviet juggernaut were the nine million people of Hungary, who found an ironic black humour in reminding each other that their nation had been defeated in every war in which it had participated for five hundred years. Now they faced the consequences of espousing the losing side in the most terrible conflict of all. Early in December 1944, the Russians forced a passage of the Danube under withering fire, with their usual indifference to casualties. A Hungarian hussar gazing on corpses heaped on the river bank turned to his officer and said in shocked wonder, ‘Lieutenant, sir, if this is how they treat their own men, what would they do to their enemies?’ After one Soviet attack north of Budapest, the defenders dragged a writhing figure off their wire. ‘The young soldier, with his shaven head and Mongolian cheekbones, is lying on his back,’ wrote a Hungarian. ‘Only his mouth is moving. Both legs and lower arms are missing. The stumps are covered in a thick layer of soil, mixed with blood and leaf mould. I bend down close to him. “Budapesst … Budapesst …”, he whispers in the throes of death … He may be having a vision of a city of rich spoils and beautiful women … Then, surprising even myself, I pull out my pistol, press it against the dying man’s temple, and fire.’

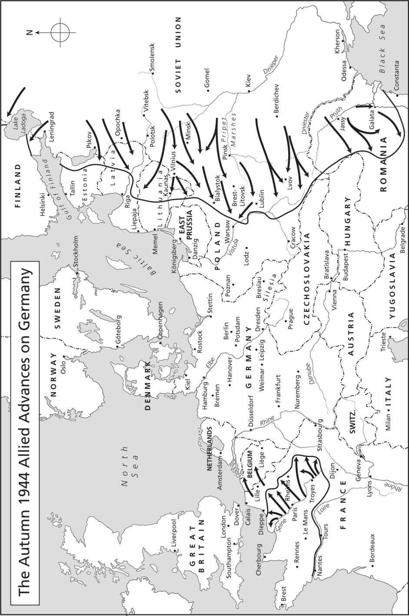

The Autumn 1944 Allied Advances on Germany

Soon afterwards, the Hungarian capital became the focus of one of the most brutal struggles of the war, scarcely noticed in the west because it coincided first with Hitler’s Ardennes offensive, and thereafter with the massive Russian offensive further north. During the last days of December, in deep snow Marshal Rodion Malinovsky’s 2nd Ukrainian

Front

closed its grip on the city. A Nazi-sponsored coup pre-empted an attempt by the Hungarian government to surrender to Stalin. Thereafter, the country fell into the hands of a fascist regime supported by the brutal Arrow Cross militia. The army fought on beside the Germans, though a steady stream of desertions testified to its soldiers’ meagre enthusiasm.

The civilian population remained curiously oblivious of catastrophe: in Budapest, theatres and cinemas stayed open until the New Year. During a performance of

Aïda

at the opera house on 23 December, an actor dressed as a soldier appeared in front of the curtain. He offered greetings from the front to the half-empty stalls, expressed pleasure that everyone was calmer and more hopeful than a few weeks earlier, then, in the words of an opera-goer, ‘promised that Budapest would remain Hungarian and our wonderful capital had nothing to fear’. Families decorated Christmas trees with ‘Window’, the silver foil strips dropped by British and American bombers to baffle German radar. Many of the city’s million inhabitants, ignoring looming disaster, spurned opportunities to flee west. Some looked forward to greeting the Russians as deliverers: hearing Malinovsky’s guns close at hand, liberal politician Imre Csescy wrote, ‘This is the most beautiful Christmas music. Are we really about to be liberated? God help us and put an end to the rule of these gangsters.’

Stalin had ordered the capture of Budapest, and at first hoped to achieve this without a battle: even when the Russians had almost completed the capital’s encirclement, they left open a western passage for the garrison’s withdrawal. The German front commander wanted to abandon the city; Hitler, inevitably, insisted that it should be defended to the last. Some 50,000 German and 45,000 Hungarian troops held their positions, knowing from the outset that their predicament was hopeless. One artillery battalion consisted of Ukrainians dressed in Polish uniforms with German insignia. An SS cavalry division was described as ‘totally demoralised’, and three Hungarian SS police regiments were classified as ‘extremely unreliable’. General Karl Pfeffer-Wildenbruch, commanding the German forces, did not leave his bunker for six weeks, and displayed unbridled gloom. One Hungarian general was so disgusted by his men’s incessant desertions that he declared haughtily that he ‘would not ruin his military career’ and relinquished command, reporting sick.

But, as so often, once battle was joined the combatants became locked in a struggle for survival which achieved a momentum of its own. On 30 December, a thousand Russian guns opened a barrage on Budapest that continued for ten hours daily, with air raids in between. Civilians huddled in their cellars, which failed to protect many from incineration or asphyxiation. After three days, Russian tanks and infantry began to push forward, squeezing the shrinking German perimeter on the Pest bank of the Danube, and meanwhile advancing into Buda yard by yard.

A Hungarian gunner officer, Captain Sándor Hanák, awaited attack on 7 January behind the wooden fence of the city racecourse. ‘The Russkis … were coming across the open track, singing and arm in arm … presumably in an alcoholic state. Kicking the fence down, we fired fragmentation grenades and machine-gun bursts into the mass. They ran to the stands, where there was a terrible bloodbath when the assault guns fired at one row of seats after another. The Germans reported about eight hundred of them dead.’ When at last the Pest bridgehead was lost and the Danube bridges blown, in Buda the garrison fought street by street, house by house. In some places the Russians drove prisoners in front of them, who shouted despairingly, ‘We are Hungarians!’ before both sides’ fire tore into them. Bizarrely, a group of seventy Russians defected to the defenders, asserting that they were more afraid of retreating – to face the NKVD’s machine-gunners behind their own front – than of coming forward to surrender. Stalin’s unwilling allies suffered heavily: on 16 January a Romanian corps reported that since October it had lost 23,000 men dead, wounded and missing – more than 60 per cent of its strength.

The Russians conscripted hapless civilians to bring forward ammunition under fire. They advanced steadily through the streets, but suffered checks and slaughter wherever they were forced to cross open spaces swept by German and Hungarian guns. The plight of the defenders was worse, however: Private Dénes Vass climbed over civilian and military wounded laid out along the corridors of his unit’s command post. A hand reached up and tugged his coat. ‘It was a girl of about 18–20 with fair hair and a beautiful face. She begged me in a whisper, “Take your pistol and shoot me.” I looked at her more closely and realised with horror both her legs were missing.’

Hunger gnawed every man, woman and child. The garrison’s 25,000 horses were eaten. Only fourteen of 2,500 animals in the city’s zoo survived – the rest were killed by Soviet fire or slaughtered for meat; for weeks, a lion roamed the underground rail tunnels, until captured by a Soviet task force dispatched for the purpose. Following a headquarters conference on 26 January, a German officer wrote: ‘Leaving the room after the meeting, several commanders openly speak about Hitler’s pig-headedness. Even some of the SS are beginning to doubt his leadership.’ The senior Hungarian general reported to the Ministry of Defence on 1 February: ‘Supply situation intolerable. Menu for the next five days per head and day: 5 gr. lard, 1 slice bread and horsemeat … Lice infestation of the troops constantly increasing, in particular among the wounded. Already six cases of typhus.’ The Luftwaffe maintained meagre supply drops, many of which fell into the Russian lines. Starving civilians were shot out of hand for raiding parachuted containers in search of food. In the maternity ward of a hospital, nurses clutched motherless babies to their breasts to provide at least human warmth, as the starving infants drifted towards death.

Throughout the siege, the persecution and murder of Budapest’s Jews continued. On the morning of 24 December, Arrow Cross militia drove up to a Jewish children’s home in Munkácsy Mihály Street in Buda, and marched its inmates and their carers to the courtyard of the nearby Radetsky barracks, where they were lined up before a machine-gun. This group was saved by a sudden local Russian advance which caused their intending executioners to take flight, but their parents had already been deported and killed. Many other Jews were led out to be shot on the Danube embankment, where a handful escaped by leaping into the ice-filled river.

A Hungarian army officer rebuked an Arrow Cross teenager whom he saw beating an old woman in a column being herded towards their execution place: ‘Haven’t you got a mother, son? How can you do this?’ The boy answered carelessly, ‘She’s only a Jew, uncle …’ An estimated 105,453 Jews died in or disappeared from Budapest between mid-October 1944 and the fall of the city. Conditions among the survivors became horrific. A witness described a ghetto scene:

In narrow Kazinczy Street enfeebled men, drooping their heads, were pushing a wheelbarrow. On the rattling contraption naked human bodies as yellow as wax were jolted along and a stiff arm with black patches was dangling and knocking against the spokes of the wheel. They stopped in front of the Kazinczy baths … behind the weatherbeaten façade bodies were piled up, frozen stiff like pieces of wood … I crossed Klauzál Square. In the middle people were squatting or kneeling around a dead horse and hacking the meat off with knives. The yellow and blue intestines, jelly-like and with a cold sheen, were bursting out of the opened and mutilated body.

The Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who was among those trapped in Budapest, strove to check the Jewish massacres, warning German commanders that they would be held responsible. But killings continued, sometimes including Hungarian police officers sent to protect Jews. Wallenberg was eventually murdered by the Russians.

By the beginning of February, as German casualties mounted and supplies dwindled, much of Budapest was reduced to rubble. Fires blazed in a thousand places as palaces, houses, public buildings and blocks of flats progressively succumbed. Explosions and gunfire persisted around the clock. Soviet aircraft strafed and bombed at low level, causing wounded men to scream in despair as they lay incapable of movement beneath the attacks. The grotesque became commonplace, such as an anti-tank gun camouflaged with Persian carpets from the opera house’s props department. Terrified horses, sobbing women and children, despairing soldiers alternately stampeded and huddled for safety.

Mastery was contested in a dozen parts of the city simultaneously. Buildings changed hands several times amid attacks and counter-attacks. Hungarian soldiers who deserted in growing numbers to the Russians were offered an abrupt choice: they might join the Red Army to fight their former comrades, or face transportation to Siberia. Those who chose the former were provided with identifying red cap ribbons, cut from parachute silk, and immediately thrown back into the battle. The Russians treated such renegades with surprising comradeliness: one rifle corps’ commander, for instance, invited Hungarian officers to dinner. After the war, it was found that the death rate had been similar among those who chose captivity and those who joined the Red Army. In a chaos of loyalties, Hungarian communist resistance groups sought to aid the Soviets, and especially to kill Arrow Cross leaders and militiamen. In late January, scores of imprisoned dissidents were shot by their fellow countrymen on the terrace of the Royal Palace, most of them after torture.

On 11 February 1945, resistance collapsed in Buda. The commander of the Hungarian anti-aircraft artillery disarmed Germans in his headquarters at the Gellert Hotel, raised a white flag, and had his men shoot those who defied him and sought to prolong resistance. That night, the remains of the garrison and its senior officers attempted to break out, some in small groups, others in crowds. Most were mown down by Soviet fire, so that the dead lay heaped in open spaces. The commander of an SS cavalry division and three of his officers chose suicide when it became plain they could not escape. Another twenty-six SS men likewise shot themselves in the garden of a house in Diósárok Street. A panzer division commander was killed by Soviet machine-gun fire. Old Colonel János Vértessy, a Hungarian, tripped and fell on his face as he hurried along a street, breaking his last remaining tooth. ‘It’s not my day,’ he said ruefully, recalling that exactly thirty years earlier he had been shot down and captured as a pilot in the First World War. Shortly afterwards, he was caught and summarily executed by the Red Army.