All Hell Let Loose (94 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Many Filipinos who escaped Japanese savagery perished under American artillery fire; Manila was reduced to rubble, making a mockery of its liberation. Up to 100,000 of its citizens died in the ruins of their capital, alongside a thousand Americans and 16,000 Japanese. Yamashita retreated to the mountainous, densely forested centre of the island, where he sustained a shrinking perimeter until August 1945. The US Eighth Army under Eichelberger continued successive amphibious operations throughout the Philippines until the end of the war, occupying islands one by one, after battles that were sometimes fierce and costly. MacArthur could claim that he had reconquered the archipelago, and inflicted defeat on its Japanese occupiers. But since those soldiers could not have been transported to any battlefield where they might influence the war’s outcome, they were as much prisoners in the Philippines as was Hitler’s large, futile garrison in the German-occupied British Channel Islands.

‘The Philippines campaign was a mistake,’ says modern Japanese historian Kazutoshi Hando, who lived through the war. ‘MacArthur did it for his own reasons. Japan had lost the war once the Marianas were gone.’ The Filipino people whom MacArthur professed to love paid the price for his egomania in lost lives – something approaching half a million perished by combat, massacre, famine and disease – and wrecked homes. It was as great a misfortune for them as for the Allied war effort that neither President Roosevelt nor the US chiefs of staff could contain MacArthur’s ambitions within a smaller compass of folly. In 1944, America’s advance to victory over Japan was inexorable, but the misjudgements of the South-West Pacific Supreme Commander disfigured its achievement.

In the first days of September 1944, much of the Allied leadership – with the notable exception of Winston Churchill – supposed their nations within weeks of completing the conquest of the Third Reich. Many Germans were of the same opinion, making grim preparations for the moment when invaders would sweep their country. A German NCO named Pickers wrote to his wife in Saarlouis: ‘You and I are both living in constant mortal danger. I have written

finis

to my life, for I doubt if I’ll come out of this alive. So I’ll say goodbye to you and the children.’ Soldier Josef Roller’s father wrote to him from Trier: ‘I have buried all the china and silver and the big carpet in the stables. The small carpet is in Annie’s cellar. I have bricked in Annie’s china where the wine used to be. So if we should have gone you will find it all, but be careful in digging, so that nothing gets broken. So, Josef, all the best and keep your head down, fondest greetings and kisses from us all, your papa.’

The German people understood that if the Russians broke through in the east, all was lost. ‘Then there’ll be nothing left but to take poison,’ a Hamburg neighbour told Mathilde Wolff-Monckeburg, ‘quite calmly, as if she was suggesting pancakes for dinner tomorrow’. It is more surprising that some Nazi followers still clung doggedly to hope. Konrad Moser was a child evacuee in one of many hostels for his kind, located beside a PoW camp at Eichstadt on the grounds that the Allies were unlikely to bomb it. Late in 1944 when his elder brother Hans arrived to take him back home to Nuremberg, the hostel’s warden said accusingly, ‘I know why you want him. You don’t believe in final victory!’ Hans Moser shook his head and said, ‘I’m on leave from the Eastern Front.’ He took Konrad back to his parents, with whom the child survived the war.

Most of Germany’s cities were already devastated by bombing. Emmy Suppanz wrote to her son on the Western Front from Marburg, describing life at home: ‘Café Kaefer is still open from 6.30 to 9 a.m. and from 5 to 10 or 11 p.m. Bits of plaster moulding fell off the ceilings in the last attack, though oddly enough the mirrors are still unbroken. The windows in the café and the flat above have gone, of course. Burschi had two rabbits, one fairly big white one called Hansi and a smaller grey one to which we had not yet given a name, and was eaten a fortnight ago. The cook wanted to kill Hansi also, but she didn’t do it. Yesterday Burschi met me with news that Hansi had seven young ones! Sepp, the town … was dreadful.’ Such news from home ate deep into the spirit of soldiers far away, fighting for their lives.

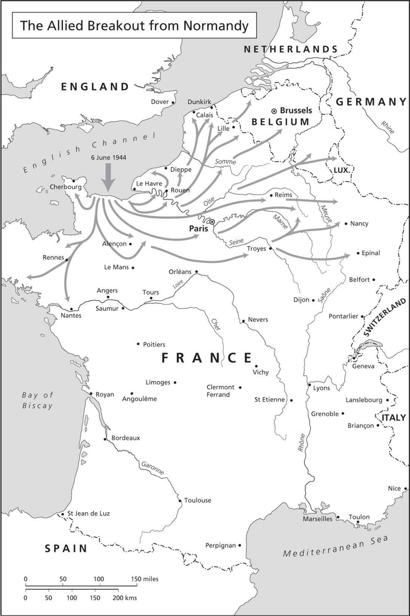

On the other side of the hill, the Allied armies’ dash across France amid rejoicing crowds infused commanders and soldiers alike with a sense of intoxication. GI Edwin Wood wrote of the exhilaration of pursuit: ‘To be nineteen years old, to be nineteen and an infantryman, to be nineteen and fight for the liberation of France from the Nazis in the summer of 1944! That time of hot and cloudless blue days when the honeybees buzzed about our heads and we shouted strange phrases in words we did not understand to men and women who cheered us as if we were gods … For that glorious moment, the dream of freedom lived and we were ten feet tall.’ Sir Arthur Harris asserted that, thanks to the support of the RAF’s and USAAF’s bombers, the armies in France had enjoyed ‘a walkover’. This was a gross exaggeration, characteristic of the rhetoric of both British and American air chiefs, but it was certainly true that in the autumn of 1944 the Western Allies liberated France and Belgium at much lower human cost than their leaders had anticipated. A flood of Ultra-intercepted signals revealed the despair of Hitler’s generals, the ruin of their forces. This in turn induced in Eisenhower and his subordinates a brief and ill-judged carelessness. With the Germans on their knees, unprecedented rewards seemed available for risk-taking: Montgomery persuaded Eisenhower that in his own northern sector of the front, there was an opportunity to launch a war-winning thrust, to seize a bridge over the Rhine at the Dutch town of Arnhem, across which Allied forces might flood into Germany.

It remains a focus of fierce controversy whether the Western Allied armies should have been able to win the war in 1944, following the Wehrmacht’s collapse in France. It is just plausible that, with a greater display of command energy, Hodges’ US First Army could have broken through the Siegfried Line around Aachen. Patton believed that he could have done great things if his tanks had been granted the necessary fuel, but this is doubtful: the southern sector, where his army stood, was difficult ground; until April 1945 its German defenders exploited a succession of hill positions and rivers to check Patton’s advance. The Allies spent the vital early September days catching their breath after the dash eastward. Patch’s Seventh Army, which had landed in the south of France on 15 August and driven north up the Rhône valley against slight opposition, met Patton’s men at Châtillon-sur-Seine on 12 September. Lt. Gen. Jake Devers became commander of the new Franco-American 6th Army Group, deployed on the Allied right flank. Eisenhower’s forces now held an unbroken front from the Channel to the Swiss border.

The Allied Breakout from Normandy

But they still lacked a usable major port. The French rail system was largely wrecked. Some planners complained that the Allied pre-D-Day bombing had been overdone, but this seems a judgement that could be made only once the Normandy battle was safely won. The movement of fuel, ammunition and supplies for two million men by roads alone posed enormous problems. Almost every ton of supplies had to be trucked hundreds of miles from the beaches to the armies, though Marseilles soon began to make an important contribution. ‘Until we get Antwerp,’ Eisenhower wrote to Marshall, ‘we are always going to be operating on a shoestring.’ Many tanks and vehicles needed maintenance. In much the same fashion that the Wehrmacht allowed the British to escape from the Continent amid German euphoria in 1940, an outbreak of Allied ‘victory disease’ permitted their enemies now to regroup. By the time Montgomery launched Operation

Market Garden

, his ambitious dash for the Rhine, the Germans had regained their balance. Their strategic predicament remained irrecoverable, but they displayed persistent stubbornness in local defence, matched by aggressive energy in responding to Allied initiatives.

On 17 September, three Allied airborne divisions landed in Holland: the US 82nd and 101st were tasked to seize river and canal crossings between the Allied front line and Arnhem; the British 1st Airborne to capture the Rhine bridge and hold a perimeter beyond it. The entire formation was dispatched to a drop zone north of the great river. The American operations were largely successful, though German demolitions at Zon enforced delay while a replacement Bailey bridge was brought forward. The British, however, furthest from Montgomery’s relieving force, ran into immediate difficulties. Ultra had revealed that the remains of 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were refitting at Arnhem. Allied commanders discounted their presence, because the formations had been so ravaged in Normandy, but the Germans responded to the sudden British descent with their usual impressive violence. Scratch local forces, many of them made up of rear-area administrative and support personnel, improvised blocking positions that drastically delayed the paratroopers’ march to the bridge. Model, Hitler’s favourite ‘fireman’ of the Eastern Front, was on hand to direct the German response. Some elements of 1st Airborne Division displayed a notable lack of verve and tactical skill: they were broken up and destroyed piecemeal while attempting to advance into Arnhem. Even the small number of German armoured vehicles within reach of the town were able to maul airborne units which had few anti-tank weapons and no tanks.

The lone battalion that reached the bridge could hold positions only at its northern end, separated from the relieving armoured force by the Rhine and a rapidly growing number of Germans. The British decision to drop 1st Airborne outside Arnhem imposed a four-hour pause between the opening of the first parachute canopies and Lt. Col. John Frost’s arrival on foot at the bridge; this provided the Germans in their vehicles with far too generous a margin of time to respond. The British might have seized the Rhine crossing by dropping glider-borne

coup de main

parties directly onto the objective, as the Germans had done in Holland in 1940, and the British at the Caen Canal on D-Day. Such an initiative would have certainly cost lives, but far fewer than were lost battering a path into Arnhem. As it was, from the afternoon of the 17th onwards, the British in and around the town were merely struggling for survival, having already forfeited any realistic prospect of fulfilling their objectives.

There was, however, an even more fundamental flaw in Montgomery’s plan, which would probably have scotched his ambitions even if British paratroopers had secured both sides of the bridge. The relieving force needed to cover the fifty-nine miles from the Meuse–Escaut Canal to Arnhem in three days, with access to only a single Dutch road – a cross-country advance was impossible, because the ground was too soft for armour. Within minutes of crossing the start-line, Guards Armoured Division was in trouble as its leading tanks were knocked out by German anti-tank weapons, and supporting British infantry became bogged down in local firefights. The American airborne formations did all that could have been expected of them in securing key crossings, but the Allied advance was soon behind schedule. The Germans were able to make their own deployments in full knowledge of Allied intentions, because they found the operational plan for

Market Garden

on the body of a US staff officer who had recklessly carried it into battle; within hours, the document was on the desk of Model, who exploited his insight to the full.

On 20 September, when XXX Corps belatedly reached Nijmegen, paratroopers of Gavin’s 82nd Airborne made a heroic crossing of the Waal in assault boats under devastating fire. They secured a perimeter on the far bank which enabled Guards Armoured’s tanks to cross the bridge, miraculously intact. There was then another twenty-four-hour delay, incomprehensible to the Americans, before the British felt ready to resume their advance on Arnhem. In truth the time loss was unimportant. The battle was already lost: the Germans were committed in strength to defend the southern approaches to Arnhem. Residual resistance by the British paratroopers on the far bank was irrelevant, and Montgomery acknowledged failure. On the night of 25 September, 2,000 men of 1st Airborne Division were ferried to safety across the Rhine downstream from Arnhem, while almost 2,000 others escaped by other means, leaving behind 6,000 who became prisoners. Some 1,485 British paratroopers were killed, around 16 per cent of each unit engaged, and 1st Airborne Division was disbanded; 474 airmen were also killed during the operation. Meanwhile the US 82nd Airborne suffered 1,432 casualties and the 101st 2,118. The Germans lost 1,300 dead and 453 Dutch civilians were killed, many of them by Allied bombing.

Apologists for

Market Garden

, notably including Montgomery, asserted that it achieved substantial success, by leaving the Allies in possession of a deep salient into Holland. This was nonsense, for it was a cul-de-sac which took the Allies nowhere until February 1945. For eight weeks after the Arnhem battle, the two US airborne divisions were obliged to fight hard to hold the ground they won in September, though it had become strategically worthless. The Arnhem assault was a flawed concept for which the chances of success were negligible. The British commanders charged with executing it, notably Lt. Gen. Frederick ‘Boy’ Browning, displayed shameful incompetence, and merited dismissal with ignominy rather than the honours they received, in a classic British propaganda operation intended to dignify disaster.

Montgomery’s cardinal error was that he succumbed to the lust for glory which often deflected Allied commanders from their cause’s best strategic interests. General Jake Devers, one of the ablest though least celebrated American army group commanders of the war, wrote afterwards about the inevitability of differences between nations on ways and means, even if they were united in the goal of defeating the enemy: ‘This is not only true of men at the highest political level … it is a natural trait of professional military men … It is unreasonable to expect that the military representatives of nations who are serving under unified command will subordinate promptly and freely their own views to those of a commander of another nationality, unless the commander … has convinced them that it is to their national interests individually and collectively.’ Because Eisenhower lacked a coherent vision, his subordinates were often left to compete for and pursue their own. Montgomery’s ambition personally to deliver a war-winning thrust, fortified by conceit, caused him to undertake the only big operation for which the Allied armies could generate logistic support that autumn across the terrain least suited to its success. He failed to recognise that the clearing of the Scheldt approaches, to enable Antwerp to operate as an Allied supply base, was a much more important and plausible objective for his army. To use a nursery analogy, in thrusting for a Rhine bridge the Allied leadership’s eyes were bigger than their stomachs.