97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (3 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

Critics of the public market took for granted the feast available to them on a daily basis; they were equally blasé about the tremendous human effort required to assemble all those varied goods: beef and pork transported by rail from the Midwest; vegetables, butter, cheese, and milk from the farms of Connecticut, New Jersey, and Long Island; stone fruits and melons from the South, along with fish and seafood shipped from all points along the Eastern Seaboard.

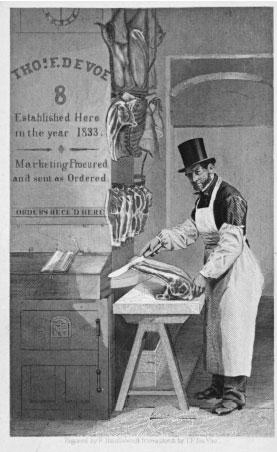

A leading defender of the markets was Thomas De Voe, a New York butcher who leased a stall in the Jefferson Market at the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Street. A portrait of De Voe shows him in typical butcher’s costume: a top hat and long apron, a knife in one hand, poised before a rack of meat, ready to slice.

Born in 1811, De Voe worked as a butcher’s apprentice as a young boy and remained with the profession until 1872, the year he was appointed superintendent of markets for the city of New York. But De Voe was an intellectual as well, intensely curious about the world of the market and how it evolved. In 1858, he presented a paper on the history of the markets to the New-York Historical Society, which he later expanded and published as

The Market Book.

His next project,

The Market Assistant

, was an encyclopedic and exhaustively researched survey of “every article of human food sold in the public markets of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn.”

11

The result of his efforts is a precise record of culinary consumption in urban America. It tells us, for example, that New Yorkers once dined on buffalo, bear, venison, moose (the snout was especially delectable), otter, swan, grouse, and dozens of other species, wild and domestic; that fish dealers offered fifteen types of bass, six types of flounder, and seventeen types of perch; and that shoppers at the produce stalls could choose between purslane, salsify, borage, burdock, beach plum, black currants, mulberries, nanny berries, black gumberries, and whortleberries.

Portrait of Thomas De Voe, scholar and defender of the New York public markets.

Science, Industry & Business Library, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Business at the public markets followed a predictable daily rhythm. It began at four in the morning, when the wholesale customers—the restaurant owners, hotel caterers, and grocers—arrived at the sprawling Washington Market to buy their supplies. Next to arrive were the well-heeled shoppers: those who could afford the choicest cuts of meat and the freshest produce. They came in person, both men and women, or sent their cooks. By afternoon, the best goods had disappeared and prices began to fall. Now it was time for the bargain shoppers, women from middle-class and poor families, to buy their provisions. But the keenest hunters of bargains were the boardinghouse cooks, the last customers of the day, who filled their baskets with leathery steaks and slightly rancid butter.

Descriptive accounts of the New York markets present scenes of great kinetic energy. Here is one especially vivid passage from

Scribner’s Monthly:

Choose a Saturday morning for a promenade in Washington Market, and you shall see a sight that will speed the blood in your veins,—matchless enterprise, inexhaustible spirit and multitudinous varieties of character…You cannot see an idle trader. The poulterer fills in his spare moments in plucking his birds, and saluting the buyers; and while the butcher is cracking a joint for one purchaser he is loudly canvassing another from his small stand, which is completely walled in with meats. All the while there arises a din of clashing sounds which never loses pitch. Yonder there is a long counter, and standing behind it in a row are about twenty men in blue blouses, opening oysters. Their movements are like clock-work. Before each is a basket of oysters; one is picked out, a knife flashes, the shell yawns, and the delicate morsel is committed to a tin pail in two or three seconds.

12

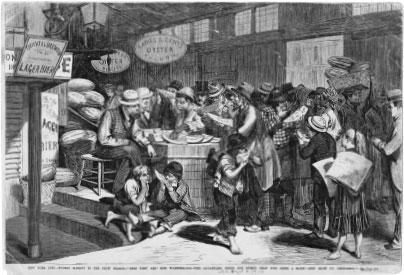

Artists were also drawn to the markets. Their challenge was to capture the ceaseless activity of the market in a single, unmoving image. One particularly successful illustration depicts the arrival of fresh Georgia watermelons at the Fulton Market. In this scene, a good cross-section of New York has swarmed the melon stand: barefoot street children, tramps, working men of color, housewives in bonnets, a mustachioed gentleman in a silk top hat. As the image makes clear, the markets were democratic in character, serving the broadest range of New Yorkers from Fifth Avenue tycoons to downtown street urchins.

The watermelon stand at the Fulton Street market, 1875.

Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

The Essex Market on Grand Street, where Mrs. Glockner did her shopping, was a three-story brick building that ran the entire length of one city block. In design, it resembled a medieval fortress with massive square towers at each corner. Like other market buildings, it served more than one purpose. Food sellers occupied the ground floor, while the upper floors were home to a courthouse, a police station, a jail, a dispensary, and, in later years, a makeshift grammar school.

The Essex Market housed twenty vegetable and poultry stalls, eight butter and cheese stalls, six fish stalls, twenty-four butcher stalls, two stalls for smoked meat, two for coffee and cake, and one for tripe. In all likelihood, this is where Mrs. Glockner bought her veal bones, pig’s knuckles, cabbage, salsify (a root vegetable much loved by the Germans), plums, and apples. It’s also where she shopped for fish.

Predictably enough, the biggest fish-eaters in pre-modern Germany lived in coastal areas along the Baltic and the North Sea. Here, fishing boats trawled for cod, salmon, whitefish, flounder, among other forms of marine life. Their most prolific catch, however, was the diminutive herring. In its fresh form, this small, silvery fish (cousin to the sardine), figured prominently in the local diet. Preserved herring, meanwhile, became an important trading commodity. Cured in brine and packed into barrels, it traveled inland and established itself in the German kitchen. In the nineteenth century, immigrants brought their taste for herring to America, where it was never too popular among native-born citizens. Still, every winter, schoonerloads of herring arrived at the wharves along the East River and were sold in the public markets, both fresh and salted. Germans, along with the Irish, British, and Scots, were the main customers. The herring found a more welcoming home in a new kind of American food shop that began to appear on the Lower East Side sometime in the 1860s. The Germans called them delicatessens.

The delicatessen shopper could choose among herring dressed in sour cream and mayonnaise, pickled herring, herring fried in butter, smoked herring, and rolled herring stuffed with pickles. There was some version of a herring salad, a fascinating composition of flavors, textures, and colors. The following is a typical example:

H

ERRING

S

ALAD

A very popular German salad is made in this manner: Soak a dozen pickled Holland herring overnight, drain, remove the skin and bones, and chop fine. Add a pint of cooked potatoes, half a pint of cooked beets, half a pint of raw apples, and six hard-boiled eggs chopped in a similar manner, and a gill each of minced onions and capers. Use French dressing. Mix well together. Fill little dishes with the mixture, and trim the tops with parsley, slices of boiled eggs, beets, etc.

13

The building at 97 Orchard Street stands atop a natural elevation that protects it from flooding, a problem that afflicted most other sections of the Lower East Side. Thanks to that subtle rise, the building’s rooftop offered sweeping views of the surrounding neighborhood. Directly to the east lay a tight grid of squat row houses. Here and there, one of the newer tenements poked up awkwardly, a brick giant among dwarves. In the courtyards formed by the grid, the square within each city block, were additional structures, “rear tenements,” as they were known, which provided New Yorkers with some of the worst housing in the city. Closer to the river, the rear tenements were replaced by factories (most were for furniture), and past them, the shipyards. Beyond lay the wharves, visible only as a thicket of ship’s masts. Facing north, the grid opened slightly, the blocks were longer and the avenues wider. The buildings were newer and taller. Tompkins Square (Germans called it the

Weisse Garten

—the “white garden”) was among the few open spaces in the city grid. Nearing the river, the landscape turned more industrial, the tenements replaced by lumberyards, slaughterhouses, and breweries. To the south, toward the narrow tip of Manhattan, lay the Five Points, a maze of skinny passageways and tottering wooden houses. Just beyond it rose the domed cupola of City Hall. To the west of Orchard Street stretched an unbroken string of saloons, restaurants, theaters, and beer halls, some large enough to accommodate a crowd of three thousand. This was the Bowery, New York’s main entertainment district. Beyond it, Broadway, the city’s widest street, sliced the island neatly down the middle.

The view from 97 Orchard embraced roughly four city wards, a geographic designation dating back to 1686, when New York’s British governor divided Lower Manhattan into six political districts, each one responsible for electing an alderman to sit on the Common Council, the city’s main governing body. As the city expanded northward, new wards were created, so by 1860 it had twenty-two. From the roof of 97 Orchard, the view encompassed the tenth ward (home to the Bowery), the seventeenth ward surrounding Tompkins Square, and the eleventh and thirteenth wards covering the industrial blocks along the river. Those same four wards made up

Kleindeutschland

, “Little Germany,” the focus of our present story and the center of German life in New York.

The residents of

Kleindeutschland

were largely urban people. They had emigrated from cities in Germany and knew how to manage in one. (Immigrants from the German countryside generally passed through New York on their way to Missouri, Illinois, or Wisconsin, wide-open states where land was cheap and they could start farms.) New York Germans, by contrast, earned their living as merchants or trades people. Many were tailors, like Mr. Glockner, but they were also bakers, brewers, printers, and carpenters. Despite their shared roots, however, the residents of “Dutch-town,” as it was sometimes called, were divided into small enclaves, a pattern that mirrored the cultural landscape of nineteenth-century Germany.

Maps of central Europe in the mid-nineteenth century show

Der Deutsche Bund

, “the German League,” a confederation of thirty-nine small and large states. The people who made up that sprawling political body, however, were bound together in much smaller groups. Nineteenth-century Germans identified themselves as Bavarians or Hessians or Saxons. Their loyalties were regional, cemented by cultural forces like religion and language. Depending largely on where he lived, a German could be Catholic or Jewish or Lutheran or Calvinist. Germans spoke a variety of local dialects that were often unintelligible to outsiders. And each region had developed its own food traditions that the immigrants carried with them to New York.

Very broadly speaking, the culinary breakdown looked something like this: Germans from southern states like Swabia, Baden, and Bavaria depended on dumplings and noodles, a class of foods which the Germans called

Mehlspeisen

(roughly, “flour foods”), as their main source of calories. Northerners, meanwhile, relied more on potatoes, beans, and pulses like split peas and lentils. Where northerners tended to use pork fat as a cooking medium, southerners used butter. Where northerners consumed large amounts of saltwater fish, southerners ate freshwater species like pike and carp. Though Germany was a nation of sausage-eaters, every region, and many cities, produced its own local version. So, Bavarians had

weisswurst

(white sausage), a specialty of Munich, while Swabians had

blutwurst

(blood sausage) and Saxons had

rotwurst

(red sausage). The residents of Frankfurt, a city in Hesse, consumed a local sausage called

Frankfurter wurst

, the ancestor of the American hot dog. Turning to baked goods, Berlin was the city of jelly doughnuts, while Dresden produced stollen, and Nuremburg made gingerbread. And finally, the liquid portion of the meal. While beer was the national beverage, Germans also enjoyed cider, the regional favorite in Hesse, while Badeners favored wine and northerners preferred a local version of schnapps.